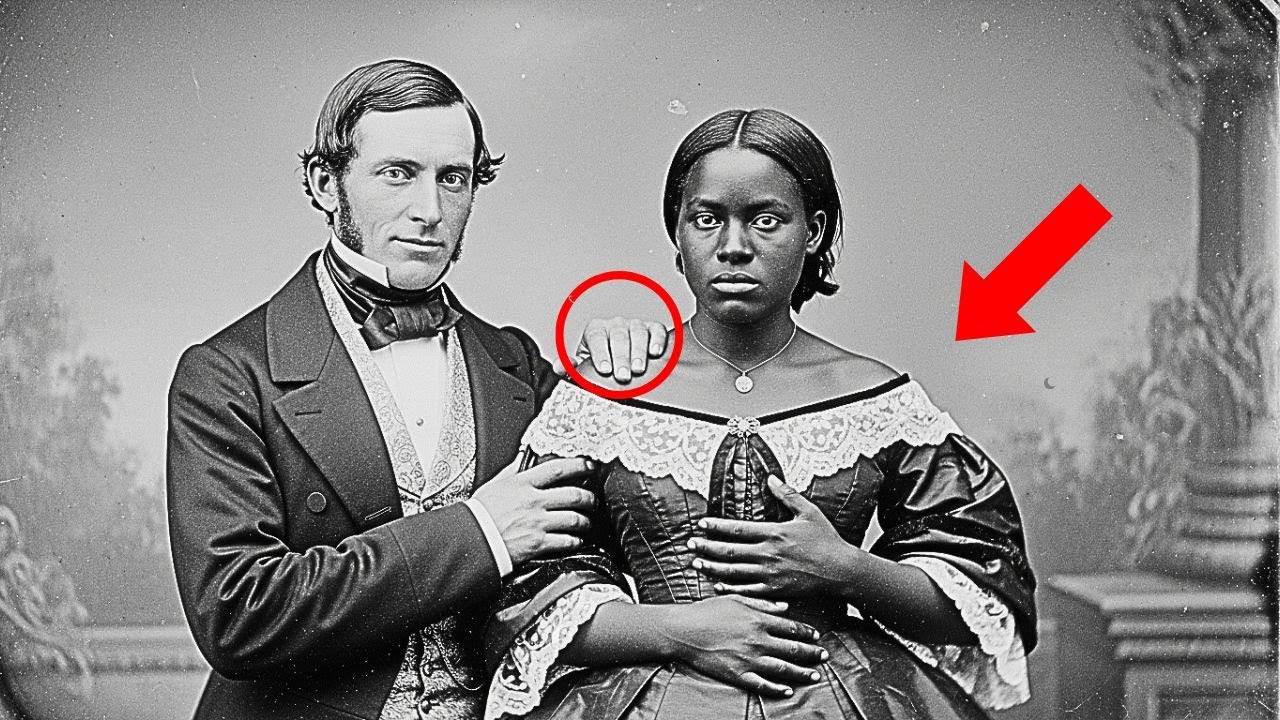

This photo of two friends seemed peaceful — but look closely at the man’s hand on her shoulder | HO

I. The Photograph That Shouldn’t Exist

The photo looked harmless at first—a man and a woman standing close, posed before a painted pastoral backdrop.

Two friends, perhaps a couple. His hand rested gently on her shoulder.

It wasn’t until Dr. Emma Richardson, senior conservator at the Charleston Historical Society, placed the daguerreotype under her microscope that the illusion began to fracture.

The light from the magnifying lamp made the silver surface gleam like water. Emma leaned closer. Beneath the faint scratches of time, she saw the pressure of his fingers, the tension in her neck, the strain in the muscles of her jaw.

It wasn’t a gesture of affection. It was control.

The ornate gilt frame had arrived a week earlier in a box of estate donations. The attached note read simply: “Mr. and Mrs. Hartwell, Charleston, 1857.”

But there was no Mrs. Hartwell in the Charleston marriage archives.

And the woman in the photograph—a Black woman in a fine silk gown, hair styled in careful ringlets—should never have appeared beside a wealthy white man in 1857 Charleston, much less in a wedding portrait.

When Emma turned the frame over and saw the handwritten label—“Mr. Jonathan Hartwell and his wife”—she felt a chill move through her bones.

Because history told her that this image should not exist.

II. The Hand That Held Power

Emma had seen thousands of 19th-century portraits. She knew the difference between tenderness and possession.

She zoomed in. His thumb pressed into the fabric of her sleeve, hard enough to distort the taffeta. Her shoulder lifted slightly away, her body trying to retreat, but his hand pinned her still.

Her eyes told the rest. Wide. Watchful. The look of a woman who knew that disobedience could cost her life.

Emma pulled up the historical database and began typing: “Hartwell, Jonathan — Charleston.”

The records painted the familiar portrait of a man born into privilege.

Jonathan Hartwell, b. 1825. Inherited Riverside Plantation—a 300-acre rice estate—at twenty-five. Owned forty-seven enslaved people, according to the 1850 census. Wealth, respectability, a name that carried weight in every Charleston drawing room.

But when Emma searched for his wife, she found nothing. No record of a white marriage. No church banns. No social announcements. Only a single line in a county ledger:

“Marriage — Jonathan Hartwell to Catherine (no surname), June 1856. Private ceremony.”

No surname. No family listed. No parish record.

In Charleston’s rigid racial order, that omission was an alarm bell.

III. A Marriage the Law Couldn’t See

By South Carolina law in the 1850s, interracial marriage was illegal. A white man wishing to marry a Black woman had to first free her and then petition the legislature for permission—a public, humiliating act few dared attempt.

Emma searched the manumission rolls. No record. No petition.

Which meant the woman named Catherine remained enslaved.

And yet there she stood in the photograph—dressed like a lady of Charleston society, pearls at her neck, lace at her cuffs, eyes filled with unspoken defiance.

Emma called her mentor, Dr. Marcus Webb, a scholar of antebellum Charleston.

He studied the photograph in silence for a long time before speaking.

“This isn’t a wedding portrait,” he said finally. “This is ownership documented.”

IV. The Woman Called Catherine

Together, Emma and Marcus combed the archives.

In the plantation records of Riverside, a single line appeared in the 1855 inventory:

“Catherine — female, age 22, house servant. Purchased at auction, September 1855.”

Six months before the supposed marriage.

She traced the sale back to the estate of Colonel Richard Thornton, who had died that year. The auction notice in the Charleston Mercury listed her as:

“Healthy female, age 22, trained in fine needlework and household management, excellent cook, literate despite prohibition.”

Literate. That word changed everything.

Somebody had taught her to read—an act illegal for the enslaved in South Carolina. It meant courage, danger, and intelligence.

A letter in the Thornton papers confirmed it.

Colonel Thornton had written in 1848:

“My late wife insisted the servant girl Catherine be taught to read Scripture. She is now too clever for her own good—asks questions that make the others restless.”

When Thornton died, Catherine was sold to pay his debts.

Jonathan Hartwell bought her.

He dressed her in silk. He placed a chain of gold around her neck. He called her his wife.

But the collar marks at her throat—thin, pale scars visible beneath lace—told the truth.

V. The Woman in the Photograph

Mary Simmons, a Charleston socialite, recorded the scandal in her diary:

November 1856. “Much gossip about Mr. Hartwell’s peculiar arrangement. He parades one of his servants as a wife, dressing her in silks and jewels. The creature is beautiful but her presumption outrageous.”

Another entry, from March 1857:

“Saw them at market. She walked two steps behind him, eyes downcast, wearing a gown worth two hundred dollars. Mrs. Henderson bumped her shoulder and she apologized profusely, though the fault was not hers. How terrible to be trapped in such a gilded cage.”

And in July 1857:

“Spoke briefly with the woman called Catherine. Her hands trembled as she clutched her reticule. I noticed bruises on her wrists.”

For Emma, these words transformed the photograph from artifact to evidence.

The studio record from Bradford’s Photography completed the puzzle:

Client: Mr. J. Hartwell. Commission: full-plate daguerreotype with female servant in formal attire. Special instruction: subject must appear as married couple. Payment: $15. Note: female servant — not wife.

Bradford knew. Everyone knew.

It was a portrait of domination masquerading as devotion.

VI. The Testimony of Samuel

In the WPA Slave Narratives collected after the Civil War, Emma found a name: Samuel, formerly enslaved at Riverside Plantation.

His words were plain and devastating:

“Mr. Hartwell bought Catherine and called her wife. We all knew what she was. She cried at night in the big house. Tried to run twice. The first time they whipped her and locked her in the attic. The second, he told her if she ran again, he’d sell her children south. She didn’t have none yet, but she understood.”

Samuel’s testimony filled in what the photograph could not: the nights behind closed doors, the silence of forced compliance.

VII. The Historian’s Verdict

Emma shared her findings with Dr. Jennifer Marshall, a historian at Howard University who studied enslaved women in the antebellum South.

Dr. Marshall examined the photo through the screen during a video call. Her tone was clinical but her eyes betrayed fury.

“This is textbook sexual slavery disguised as marriage,” she said.

“White owners staged these relationships to legitimize what they were doing. They gave the women fine clothes, better rooms, jewelry. But consent is impossible when you own the other person.”

She pointed to Catherine’s hands in the photo.

“See how they’re clasped tight over her stomach? That’s a defensive posture. She’s bracing herself.”

Emma nodded, unable to speak.

“The dress is a uniform of subjugation,” Dr. Marshall continued. “It marks her as his property as clearly as chains would.”

The more they studied, the more the photograph revealed—not just one crime, but a system of them.

VIII. Death in Childbirth

Emma found Catherine’s name one last time in the Riverside ledger.

“Catherine — deceased. February 15, 1859. Died in childbirth. Infant deceased. Total loss $200.”

A woman reduced to a line in an account book.

One month later, Hartwell purchased another “house servant,” Amelia, age nineteen.

By 1861, there was another daguerreotype. The same man. The same pose. The same hand on a new shoulder.

And then another, and another—five women over fifteen years.

All gone, one by one, from the record.

IX. The Descendant

When Emma contacted Elizabeth Hartwell Morrison, Jonathan’s modern descendant, she expected defensiveness. Instead, Elizabeth wept.

“I knew he owned slaves,” she said quietly, “but I didn’t know this.”

Emma showed her the evidence: the ledger entries, the sale receipts, the testimonies.

Elizabeth stared at Catherine’s face for a long time.

“He bought women like furniture,” she whispered.

“Yes,” Emma said. “There was even a name for it—the fancy trade. Women sold for sexual use, dressed like white ladies to disguise the violence.”

Elizabeth closed her eyes. “Then we have to tell it. All of it.”

X. The Hidden Pattern

What began as one photograph became a reckoning.

Within months, Emma and Dr. Marshall uncovered over thirty similar portraits across Charleston—white men with enslaved women posed as wives.

Every image followed the same choreography:

The man’s possessive hand.

The woman’s averted eyes.

Dresses too fine for their station.

A stillness that wasn’t peace, but endurance.

Dr. Angela Freeman of the National Museum of African American History and Culture flew to Charleston to examine the findings.

“These aren’t family portraits,” she said. “They’re crime scenes.”

The museum announced a groundbreaking exhibition:

False Wives: Enslaved Women and the Photography of Possession.

XI. The Exhibition

When the gallery opened in Washington, D.C., the air was heavy with silence.

Visitors moved slowly through rooms filled with portraits once mislabeled as “servants in Sunday dress.”

At the center hung Catherine’s image—enlarged, framed in light. Around her, the evidence:

The plantation ledger.

Mary Simmons’s diary entries.

Samuel’s testimony.

The death record that priced her life at two hundred dollars.

Beside it, a plaque read:

“She was not a wife. She was a woman enslaved, photographed to make her bondage look like love.”

Dr. Freeman spoke at the opening:

“We have long spoken of slavery in terms of labor and economics. But it was also a system of sexual violence. These images show us what polite society tried to hide—the rape that wore the costume of romance.”

XII. The Woman Who Survived

Three months later, Emma received an email from a woman named Margaret Wright.

“My great-great-grandmother was named Catherine,” she wrote. “She was born enslaved in South Carolina. After the war, she moved north, founded a school, and lived to be seventy-three.”

Margaret attached a photograph.

A woman in plain clothes, arms crossed, standing proud before a wooden house. The same eyes. The same face. But now she met the camera on her own terms.

“She kept this photo,” Margaret said when they met. “She told my grandmother, ‘This is who they tried to make me be. But this is who I became.’”

For the first time, Emma cried for Catherine—not from horror, but from awe.

XIII. The Memorial

In Charleston’s Hampton Park, where Riverside Plantation once stood, a bronze statue now rises:

A woman in a 19th-century dress, holding a book to her chest, her gaze lifted toward the sun.

At her feet, an inscription:

“In memory of Catherine and all enslaved women forced into false marriages.

Their silence was not consent. Their suffering was not love.

Their story will not be forgotten.”

Descendants of both enslaved and enslavers gathered for the unveiling. Some prayed. Others stood in silence.

Emma placed her hand on the plaque, tracing the raised letters.

“We see you now,” she whispered. “We remember.”

XIV. The Photograph’s Final Truth

The daguerreotype remains under glass in the museum’s climate-controlled vault. It no longer hangs as art but as testimony.

At first glance, it still looks tranquil: a man, a woman, a moment frozen in time.

But look closer.

Look at his hand on her shoulder.

At the tension in her neck.

At the defiance in her eyes.

That’s where the truth hides—in the small, silent details that history tried to smooth away.

Because history, Emma realized, isn’t just what survives.

It’s what we’re finally brave enough to see.

News

Teen & Her Uncle Went For A Vacation In Hawaii, She Never Returned–2 Months Later, Her Mom Found Out | HO”

Teen & Her Uncle Went For A Vacation In Hawaii, She Never Returned–2 Months Later, Her Mom Found Out |…

‘𝐏𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐜𝐢𝐩𝐚𝐥 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐘𝐞𝐚𝐫’ Impregnates 3 Students & Infected Them with 𝐇𝐈𝐕 – 𝐊𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐞𝐝 2, and the Last One | HO

‘𝐏𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐜𝐢𝐩𝐚𝐥 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐘𝐞𝐚𝐫’ Impregnates 3 Students & Infected Them with 𝐇𝐈𝐕 – 𝐊𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐞𝐝 2, and the Last One |…

The Billionaire’s Heir Who Turned a Marriage Into Torture — Connie Ng’s Nightmare | HO!!

The Billionaire’s Heir Who Turned a Marriage Into Torture — Connie Ng’s Nightmare | HO!! She was the adored only…

50 YO Man Travels to Barbados to Meet His Online Lover, Only to Discover She is A Disable… Ends in | HO!!

50 YO Man Travels to Barbados to Meet His Online Lover, Only to Discover She is A Disable… Ends in…

50 YO Man Travels to Barbados to Meet His Online Lover, Only to Discover She is A Disable… Ends in | HO!!

50 YO Man Travels to Barbados to Meet His Online Lover, Only to Discover She is A Disable… Ends in…

She 𝐇𝐚𝐝 𝐒𝟑𝐱 With Him Once — And He 𝐃𝐢𝐞𝐝 Rotting From the Inside | HO!!

She 𝐇𝐚𝐝 𝐒𝟑𝐱 With Him Once — And He 𝐃𝐢𝐞𝐝 Rotting From the Inside | HO!! On a wind-carved ridge…

End of content

No more pages to load