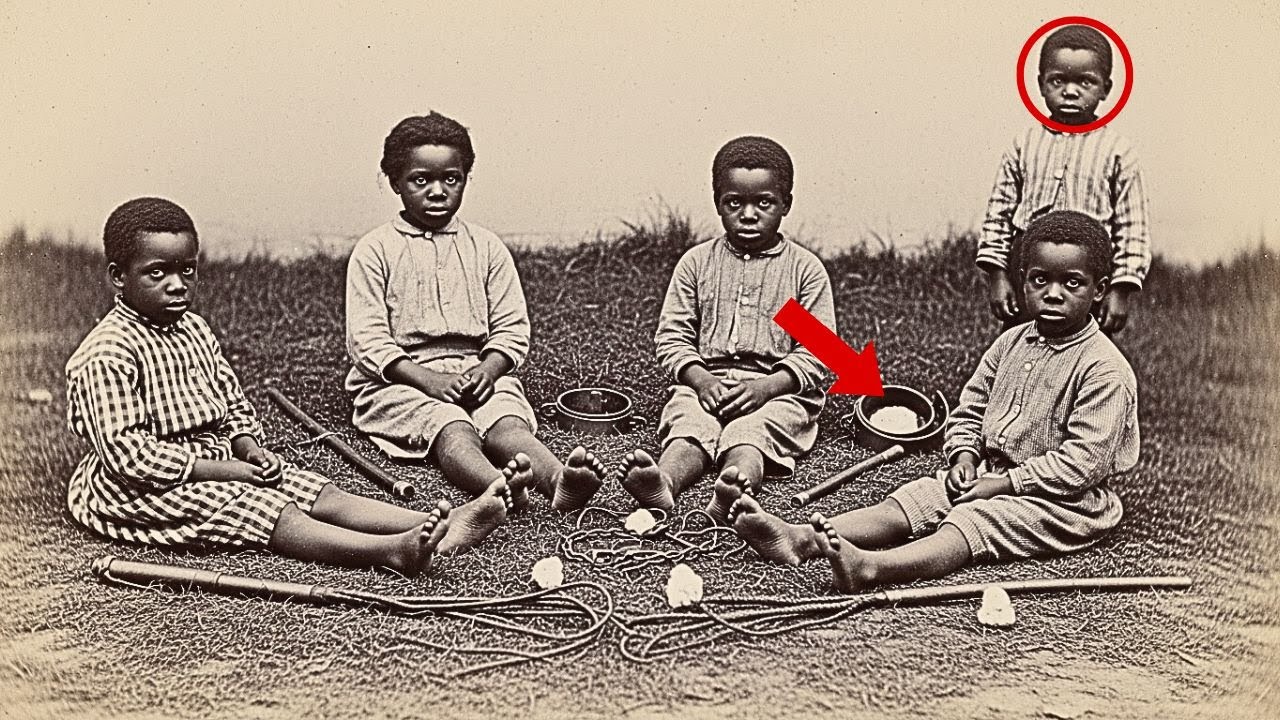

This Photo Seemed to Show Children at Play — Until Experts Saw What Was on the Ground | HO!

At first glance, it looked innocent.

A group of five children on a sunlit lawn, their bare feet dusted with Georgia soil, their postures caught mid-motion — as if a moment of carefree laughter had been frozen forever by an early photographer.

The sepia photograph, dated 1858, arrived one quiet morning at the National Museum of African-American History in Washington, D.C. Archivist Dr. James Carter unfolded the acid-free paper that protected it, expecting yet another example of the South’s favorite lie — the “happy plantation child.”

“Another piece of propaganda,” he murmured. He’d seen dozens of such images — pictures commissioned by plantation owners to portray slavery as gentle and civilized.

But as he adjusted his magnifier, something beneath the children’s feet caught his eye.

And suddenly, the illusion shattered.

The Hidden Horror Beneath Their Feet

Around the children’s small, dirt-smudged feet lay objects the photographer clearly hadn’t meant to highlight:

Tiny iron shackles, half-buried in the ground.

A thin whip disguised as a stick.

A set of small, sharp cotton-picking tools.

And behind the smallest boy — barely seven years old — the glint of a metal collar hidden in the grass.

“My God,” whispered his assistant, Helen, as she leaned over his shoulder.

“They weren’t playing,” James said, his voice tight. “They were posing under orders. Look at their eyes.”

Zooming closer, he saw what he meant. Beneath the faint smiles demanded for the camera, the children’s eyes were not joyful. They were terrified — all except the smallest boy, whose gaze met the lens directly, not with fear, but with quiet defiance.

Turning the photograph over, James read the faded handwriting:

“Fair View Plantation, Georgia, 1858. Master Williams’ Amusements.”

Beneath that, in a different hand, one chilling note:

“Thomas, age 7 — sold three days after.”

The Boy With the Defiant Eyes

“I need to find out who Thomas was,” James said, already feeling the historian’s mixture of obsession and duty.

Over the next few days, he transformed his workspace into a detective’s board — the photograph at the center, surrounded by maps, sale records, and plantation ledgers.

Helen returned from the archives carrying a ledger marked Fair View, 1858.

“Owned by the Henderson family,” she said. “William Henderson Jr., age nineteen — must be the ‘Master Williams’ mentioned.”

A sale record dated June 18, 1858, confirmed it:

“Boy, Thomas — age seven. Purchased by Nathaniel Reed of Charleston. $475.”

Three days after the photograph.

“Why photograph children right before selling them?” Helen wondered.

“Because this wasn’t meant as a keepsake,” James replied grimly. “This was proof of value — and propaganda.”

Thomas’s eyes in the photograph now seemed to challenge him directly.

A Child Who Could Read

Searching Reed’s plantation papers in Charleston, James uncovered a remarkable note:

“Boy Thomas, literate contrary to indication. Discovered reading in the stables one week after purchase. Punishment administered. Value diminished.”

“He could read,” James said softly. “At seven.”

Helen paled. “Someone risked everything to teach him.”

Further down the record, another line:

“July 3, 1858 — Boy Thomas escaped. Bloodhounds dispatched.”

A seven-year-old runaway.

“Did he survive?” Helen asked.

James didn’t answer. He simply stared again at that tiny face in the photograph — the boy who dared to look straight into history’s camera.

The Signature in the Shadows

Three days later, under ultraviolet light, James discovered something almost invisible along the bottom edge of the image — faint writing scrawled in another hand:

“Remember them. — T.W.W.”

A signature.

Searching 1850s photography registries, James found a match: Thomas W. Woodson, a free Black photographer working in Savannah during the same period.

“If Woodson took this photograph,” James told the museum’s director, Dr. Amelia Phillip, “then it wasn’t propaganda. It was evidence — hidden truth disguised as plantation art.”

Further digging confirmed his suspicion. Abolitionist letters from the era referenced “photographs from W— that show the truth beneath the lie.”

Woodson, it seemed, had risked his life to document the brutality of slavery — embedding messages in the very images commissioned to conceal it.

Martha’s Secret

Meanwhile, Helen’s search of the Reed Plantation records uncovered something startling:

“Boy Thomas reassigned to kitchen duties under Cook Martha — restricted from field labor.”

“That’s unusual,” James said. “Why keep a disobedient child so close to the main house?”

The answer came in a letter from Reed himself:

“Martha claims the boy is her grandson. Threatened to poison the household if he is sold. As she is the finest cook in Charleston, I have acquiesced for now.”

James exhaled. “She protected him.”

During a later visit to the old Reed Plantation site, now a museum, James toured the kitchen house where Martha had once worked. Beneath a loose floorboard found decades earlier, conservators had recovered a small bundle:

A child’s reading primer, its margins filled with shaky letters.

A carved wooden figure.

And a note written in crude handwriting: “Thomas learning good. Dangerous, but proud.”

“She was teaching him to read,” Helen whispered.

And perhaps, James realized, she was preparing him for something bigger — escape.

Flight to Freedom

In 1861, as the Civil War erupted, a Charleston newspaper reported:

“Cook and boy flee Reed Plantation amid chaos. Reward offered.”

“They got away,” James said, almost smiling for the first time.

Tracing their possible route, he consulted Dr. Vanessa Johnson, an expert on the Underground Railroad. She confirmed that Charleston had an active network aiding enslaved families.

Among the papers of abolitionist William Still, they found a letter dated December 1861:

“Received M. and her grandson T. from Charleston. Boy shows remarkable literacy and carries certain images of importance.”

James froze. “Images — photographs.”

If Woodson had indeed documented the plantation’s cruelty, he might have given Thomas the prints for safekeeping — and to bear witness beyond the South.

From Child to Witness

Philadelphia’s 1862 school records showed a “Thomas, age 11 — advanced reader.”

By 1864, Union Army documents listed a youth named T., serving as a guide for troops in Georgia — valued for his knowledge of plantation roads.

“He would’ve been thirteen,” Helen noted.

“Children didn’t stay children long,” James replied.

When the war ended, a Freedmen’s Bureau school listed Thomas, age 15 — assists in teaching younger pupils. Exceptional aptitude for science and writing.

Then came the photograph that changed everything.

In an 1867 daguerreotype preserved in a private collection, a young Black man stood proudly beside a camera. On the back, an inscription:

“Studio apprentice Thomas — with gratitude, T. Woodson.”

Woodson, the secret photographer of slavery, had taken the boy under his wing.

“He went from being the subject of a photograph,” Helen said quietly, “to the man behind the lens.”

The Photographer of Freedom

Over the next two decades, Thomas emerged under new names: first T. Walker, then Thomas W. Freeman.

He opened studios in Boston and later Chicago, advertising “Authentic Portraits — True Dignity in Every Image.”

His photographs of Black families — proud, ordinary, alive — challenged the stereotypes still saturating post-Reconstruction America.

A Chicago newspaper described him as “a man who shows the Negro as he is — neither spectacle nor servant.”

But in 1891, tragedy struck.

A fire consumed his Chicago studio.

Police reports hinted at arson. Thomas had recently photographed the aftermath of a lynching for journalist Ida B. Wells, capturing details that contradicted official accounts.

Within days of the images’ circulation, his studio burned to the ground.

Beaten by unknown assailants, Thomas refused to be silenced. In a surviving letter, he wrote:

“They can burn my studio, but not my resolve. Some images survived — those I kept closest.”

The Trunk in the Attic

After 1892, Thomas Freeman vanished from the public record — until James found him again, decades later, on a small farm outside Chicago.

There, he had lived quietly with his wife, Ruth, a teacher, and two children.

And in the attic of their granddaughter Elizabeth Carter’s home, James finally found what he hadn’t dared hope still existed.

A weathered trunk.

Inside were hundreds of photographs spanning fifty years — portraits, street scenes, families, laborers — a visual history of Black America through one man’s eyes.

And among them, carefully wrapped in cloth, lay the plantation photograph — the very image that had started James’s investigation.

“He kept it all his life?” James asked softly.

Elizabeth nodded. “He said it reminded him of where he came from — and why he kept taking pictures.”

At the bottom of the trunk, James found a small notebook titled From Property to Photographer.

Its first line read:

“I was seven when a man named Woodson risked his life to show the world what slavery was. He taught me that a camera could be more powerful than a rifle.”

Full Circle

Six months later, the museum unveiled its landmark exhibition:

“From Property to Photographer: The Extraordinary Journey of Thomas Walker Freeman.”

At its center hung the haunting 1858 photograph — no longer mislabeled as plantation nostalgia, but reinterpreted as a coded act of resistance.

Around it, visitors saw the full arc of Thomas’s life — from enslaved child to free artist, from subject to storyteller.

Students paused before the image, studying the eyes of the boy who had once stared down the lens of history.

“What strikes me most,” James told them, “is how Thomas reclaimed the very tool that once dehumanized him. Photography, which once made him property, became his weapon of truth.”

As crowds moved through the gallery, Thomas’s words appeared across a final wall in bold script:

“To photograph is to remember. And to remember is to resist.”

Standing beside his ancestor’s image, Elizabeth Carter whispered, “He’d be amazed to see this — not just his work honored, but his truth finally seen.”

And under the museum lights, the boy’s defiant gaze — once hidden beneath the lie of play — met theirs across a century, unflinching, unforgotten.

News

1 MINUTE AGO: Rob Reiner’s Daughter Tracy Speaks Out After Her Parents’ Deaths | HO!!

1 MINUTE AGO: Rob Reiner’s Daughter Tracy Speaks Out After Her Parents’ Deaths | HO!! For decades, the Brentwood home…

After Decades, Soon Yi – Previn Finally Admits the Truth About Her Marriage to Woody Allen | HO!!

After Decades, Soon Yi – Previn Finally Admits the Truth About Her Marriage to Woody Allen | HO!! For more…

Dean Martin STOPPED Mid-Song When He Saw An Old Man Being Dragged Out By Security. | HO!!

Dean Martin STOPPED Mid-Song When He Saw An Old Man Being Dragged Out By Security. | HO!! Dean Martin was…

At Age 54, Rozonda ‘Chilli’ Thomas FINALLY Reveals Her TRAGIC Story! | HO!!

At Age 54, Rozonda ‘Chilli’ Thomas FINALLY Reveals Her TRAGIC Story! | HO!! For decades, she was America’s dream girl….

A Mafia Boss Humiliated Dean Martin in Public — His Response Changed Hollywood | HO!!

A Mafia Boss Humiliated Dean Martin in Public — His Response Changed Hollywood | HO!! Las Vegas, February 12, 1962,…

MOTHER Watches As Husband & Son ᴀʙᴜsᴇᴅ Her Disabled Daughter For 2 Years, Got Her Pregnant & Brutal | HO!!!!

MOTHER Watches As Husband & Son ᴀʙᴜsᴇᴅ Her Disabled Daughter For 2 Years, Got Her Pregnant & Brutal | HO!!!!…

End of content

No more pages to load