This portrait of two friends looks sweet — but experts uncover this child slave’s dark secret | HO

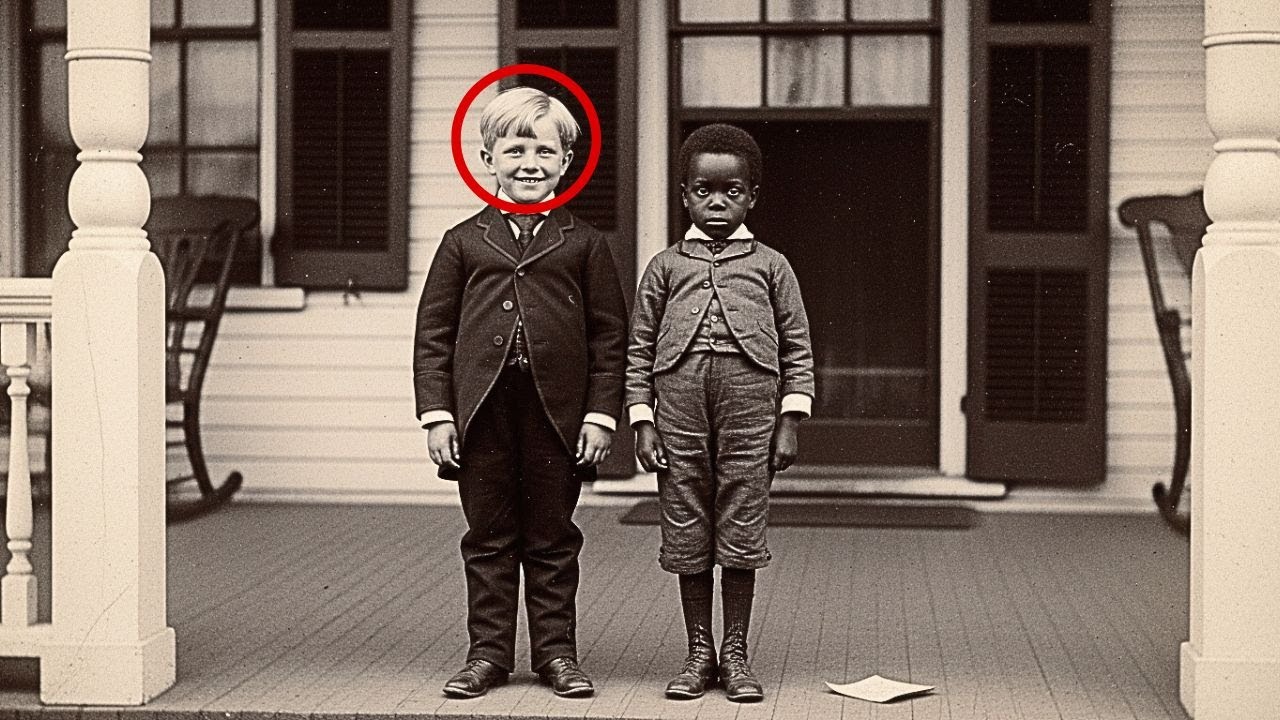

When Dr. Rebecca Morgan first lifted the faded sepia photograph from its protective sleeve inside Emory University’s Special Collections Department, she expected nothing unusual. It was dated April 13, 1857 — another stiff, formal portrait from the antebellum South.

Two boys stood side by side on the porch of a grand Georgian home. One white, one Black. Both wearing fine clothes. Both appearing about eight years old.

The white boy — William Harrison — smiled easily in his tailored suit, his polished shoes catching the sunlight. The Black child beside him — smaller, thinner, his jacket too large — stood perfectly still, his gaze unflinching, his expression unreadable.

To most, it looked like a rare sentimental photograph: two childhood companions caught in a fleeting moment of friendship. But when Morgan leaned closer, something near the Black boy’s feet caught her attention — something the camera was never meant to record.

A scrap of paper.

She reached for her magnifying glass. Her heart slowed, then began to pound.

Printed on the crumpled sheet, half-visible, were the words:

“Healthy Negro boy, Elijah, age 8. Suitable for house or field.”

And the date: April 15, 1857 — two days after the photograph was taken.

Beneath the official date stamp, another handwritten note, faded but legible, read:

“William with house boy — Spring 1857.”

And then, in a smaller, unfamiliar hand:

“Remember Elijah.”

It wasn’t a family portrait. It was a farewell.

A Child About to Vanish

Morgan froze. “This isn’t just a photograph,” she whispered. “It’s evidence.”

With her research assistant Daniel Price, she began tracing every lead. Plantation records. Auction ledgers. Obscure estate documents buried in Georgia’s archives.

The trail led to Magnolia Creek Plantation, near Wilkes County — the Harrison family estate. A ledger entry confirmed their financial collapse after the cotton blight of 1856. To cover their debts, they began selling “assets,” including enslaved children.

On the auction list for April 15, 1857:

“Boy Elijah — age 8 — house-trained.”

Beside the entry: Sold to James Fletcher, Charleston — $675.

For the first time in 168 years, the boy in the photograph had a name.

And a fate.

The Photographer’s Hidden Agenda

Digging through rare collections, Morgan’s team found something unexpected — a letter from the photographer himself.

Frederick Simmons, a traveling portraitist who worked for plantation owners, had left behind a small journal and correspondence that changed everything.

In one letter to an abolitionist contact in Boston, he wrote:

“I send these images not for publication, as it would endanger many, but as evidence of what words alone cannot convey.”

He was documenting the brutality of slavery from the inside.

In his journal entry for April 13, 1857, Simmons confessed:

“The Harrison boy demanded much attention. The other child, Elijah, remained still as stone. He knows what comes. The auction notice fell from Harrison’s pocket during the sitting. I repositioned it slightly rather than removing it. Small acts of truth are all I can manage.”

Morgan set the journal down. “He meant for that notice to be seen,” she said quietly. “He wanted the world to know what was coming.”

Charleston, 1857 — A Dangerous Kindness

Following the sale, Elijah was sent to James Fletcher, a shipping magnate in Charleston. His household ledgers listed:

“Boy Elijah — assigned to Mrs. Fletcher’s service.”

That’s where the story could have ended — another child lost to history. But in Emily Fletcher’s private letters, Rebecca found a miracle of conscience.

One note to her sister in Philadelphia read:

“The child came to us already knowing his letters. To extinguish such a light would be a sin greater than to nurture it in secret.”

Mrs. Fletcher began secretly teaching Elijah to read and write. Her society friends, part of a discreet “reading circle,” included northern sympathizers who quietly supported the abolitionist cause.

Elijah, the “boy from Magnolia Creek,” was learning forbidden knowledge — an act that could have cost both their lives.

Then came war.

The Boy Who Ran

In 1862, Charleston was tightening under Union blockade. Panic gripped wealthy families. Slaves were sold, relocated, or fled.

Among the chaos, a brief Confederate report surfaced:

“Negro boy, approx. age 13, missing from Fletcher residence. Suspected runaway, possibly aided by Unionist sympathizers.”

Elijah had escaped.

Morgan traced him north through Quaker journals and Underground Railroad records. A coded entry in educator Hannah Wells’ 1862 diary recorded:

“Received a young scholar from Charleston, age about thirteen. Shows remarkable aptitude. Carries a photograph of his former life. Says he keeps it to remember.”

He’d kept the original image — the one taken before the auction.

Under Wells’s care in Philadelphia, Elijah continued his studies, excelling in math and music. But even in safety, he couldn’t forget.

In one note to Wells, he wrote:

“If I can learn, perhaps I can help others remember what they tried to erase.”

A Spy, a Scholar, and a Return

Union intelligence files from 1863 mention “a young Negro informant from Charleston” supplying maps of Confederate shipping routes.

“He became a spy,” Morgan said, astonished. “At fourteen.”

His intimate knowledge of Charleston’s docks — gained during his years of enslavement — was invaluable to the Union cause.

A surviving photograph from 1864 shows a teenage Black scout among Union officers. His posture. His eyes. It was him — the same gaze from the 1857 portrait, now older, defiant, free.

In the aftermath of war, Freedmen’s Bureau records list Elijah Freeman — age sixteen — teacher’s assistant, Charleston Freedmen’s School. He had chosen his own surname: Freeman.

His application to study in the North contained a single line that silenced Morgan when she read it aloud:

“I seek education not only for myself, but to ensure others like me are never again denied the power of knowledge.”

He was accepted to Oberlin College in 1868 — one of the few institutions that admitted Black students.

From Property to Professor

At Oberlin, Elijah studied education and history, quickly distinguishing himself. A surviving essay from 1870 captures his transformation:

“I carry within me two children — the enslaved boy who stood for a photograph, and the free man who now writes these words. Education is the bridge between them.”

After graduation, he became Professor Elijah Freeman, teaching at a Freedmen’s school in Washington, D.C. But his mission was larger than teaching — he began collecting stories, documents, and photographs from the formerly enslaved.

He called it “The Archive of Freedom.”

In one letter, Freeman explained his purpose:

“The nation has recorded every chain, every sale, every cruelty. I will record every triumph, every act of survival, every child who learned to read despite the law.”

By the 1880s, his Freeman Historical Collection had become one of the first archives of African-American testimony, a precursor to modern oral history. He used photography — the same medium that once objectified him — as a weapon of remembrance.

The Return to Magnolia Creek

In 1885, Freeman returned to the South. He stood before the ruins of Magnolia Creek Plantation, camera in hand.

His journal entry reads:

“Here I waited to be sold. Here I return as witness.”

He photographed the crumbling house, titling it “Where William played while I awaited sale.” The image, haunting and symmetrical, became one of the most reproduced photographs of Reconstruction-era America.

Freeman’s work chronicled both progress and regression — the rise of schools and the return of racial violence, the birth of hope and the birth of Jim Crow.

By the 1890s, his collection had grown vast: hundreds of photographs, testimonies, and letters documenting the first generation born free.

And in the center of it all, displayed behind glass, was the photograph that started everything — “William with house boy, Spring 1857.”

The Reunion

In 1901, at age fifty-two, Freeman received a letter with a Boston postmark.

“Dear Professor Freeman,

I believe you may be the boy Elijah from my father’s photograph.

I am William Harrison Jr.”

Freeman’s reply was careful, dignified:

“Your letter has found the boy from that photograph, though he exists now only in memory. The man you write to welcomes a meeting — on ground where I am professor, not property.”

The two men met at Howard University, where Freeman taught history and photography. A photograph captured their encounter — the former master’s son and the former slave, seated side by side, surrounded by books and framed images of emancipation.

In his diary, Freeman wrote:

“Harrison remembers us as playmates. I remember the day he smiled while I stood waiting to be sold. Yet I see sincerity in his eyes. Perhaps we are both haunted by that photograph — he by what it hid, I by what it revealed.”

Harrison brought plantation journals that contained Elijah’s parents’ names — details the professor had never known.

“The discomfort of our meeting was worth that truth,” Freeman wrote.

Legacy of the Photograph

When Dr. Morgan stood before the same image more than a century later — now displayed at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture — she felt the boy’s steady gaze still cutting through time.

The exhibition, “From Object to Author: The Life of Professor Elijah Freeman,” centered around that haunting portrait.

Beside it hung Freeman’s later works — dignified portraits of Black teachers, families, and veterans. The contrast was staggering: the enslaved child turned documentarian of his own people’s history.

“What moves me most,” Morgan told the gathered historians, “is how he transformed the camera — once used to objectify — into a tool of empowerment and remembrance.”

In his own words, written shortly before his death in 1910, Freeman left the final statement of his life’s purpose:

“I began as the subject of history — photographed as property, recorded in ledgers. I will end as the author of history, having preserved the truth of those who endured and prevailed.”

Epilogue: The Boy Who Refused to Disappear

As visitors file past the glass case that holds the original Magnolia Creek photograph, they often linger — studying the faded ink, the torn auction notice, and the gaze of the child who somehow knew that history would one day look back.

In that moment frozen in 1857, the boy Elijah stood beside the son of his owner, both dressed as equals only for the camera.

Two days later, he was sold.

A lifetime later, he reclaimed his story — and in doing so, gave voice to millions who never could.

Now, more than 160 years after the shutter clicked, the photograph remains what its creator intended: a small act of truth that refuses to fade.

News

1 MINUTE AGO: Rob Reiner’s Daughter Tracy Speaks Out After Her Parents’ Deaths | HO!!

1 MINUTE AGO: Rob Reiner’s Daughter Tracy Speaks Out After Her Parents’ Deaths | HO!! For decades, the Brentwood home…

After Decades, Soon Yi – Previn Finally Admits the Truth About Her Marriage to Woody Allen | HO!!

After Decades, Soon Yi – Previn Finally Admits the Truth About Her Marriage to Woody Allen | HO!! For more…

Dean Martin STOPPED Mid-Song When He Saw An Old Man Being Dragged Out By Security. | HO!!

Dean Martin STOPPED Mid-Song When He Saw An Old Man Being Dragged Out By Security. | HO!! Dean Martin was…

At Age 54, Rozonda ‘Chilli’ Thomas FINALLY Reveals Her TRAGIC Story! | HO!!

At Age 54, Rozonda ‘Chilli’ Thomas FINALLY Reveals Her TRAGIC Story! | HO!! For decades, she was America’s dream girl….

A Mafia Boss Humiliated Dean Martin in Public — His Response Changed Hollywood | HO!!

A Mafia Boss Humiliated Dean Martin in Public — His Response Changed Hollywood | HO!! Las Vegas, February 12, 1962,…

MOTHER Watches As Husband & Son ᴀʙᴜsᴇᴅ Her Disabled Daughter For 2 Years, Got Her Pregnant & Brutal | HO!!!!

MOTHER Watches As Husband & Son ᴀʙᴜsᴇᴅ Her Disabled Daughter For 2 Years, Got Her Pregnant & Brutal | HO!!!!…

End of content

No more pages to load