Tourists Vanished in the Utah Desert in 2010 — In 2018 Skeletons Were Found Seated in a Sealed Mine | HO!!

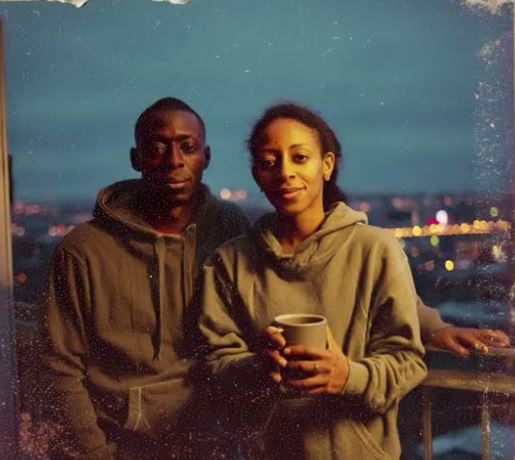

In the scorched, red-rock wilderness of Utah’s San Juan County, the summer of 2010 swallowed two promising young lives with barely a ripple. Elijah Sinclair, a doctoral geology student from Atlanta, and his wife Nia, an acclaimed photographer, vanished while researching the region’s Cold War-era uranium mines.

The official story—delivered in a matter-of-fact press conference by a local sheriff—was simple: two city kids, unprepared for the desert, had wandered off and perished. For eight years, that was the accepted truth.

But in 2018, a government crew, tasked with sealing abandoned mines, blasted open the entrance to a forgotten shaft. What they found inside would shatter the official narrative, expose a web of greed and racism, and finally reveal the truth behind the Sinclairs’ disappearance—a truth as chilling as the desert nights.

The Vanishing

Elijah Sinclair’s last email to his father, Samuel, arrived at 9:15 p.m. on a Tuesday. The subject line—“Update from the red planet”—was typical of his wry humor. He wrote of the Morrison Formation, the uranium boom, and the haunting beauty of the landscape. But one paragraph stood out: “We met a local deputy today, a real old-timer… He was a bit territorial about the old mines, warning us away from some unstable ones, but pointed us toward some interesting formations.”

Samuel, a retired history professor and veteran of the civil rights movement, felt a prickle of unease. He knew the “cultural geology” of places like this. For two Black academics from Atlanta, a “territorial” deputy in remote Utah could be more than just a character.

When Elijah and Nia failed to call as promised, Samuel’s anxiety deepened. By Sunday, a Utah State Police trooper informed him their rental SUV had been found abandoned at a remote trailhead. A search was underway. Samuel and his wife, Eleanor, caught the first flight west.

They were greeted not by urgency, but by a performance. Sheriff Brody Wilcox, a caricature of the rural lawman, assured them that “the desert ain’t Atlanta.” The search, Samuel quickly realized, was perfunctory—a single deputy, a few volunteers, and a narrative already forming.

Deputy Dale Lteran, the “old-timer” from Elijah’s email, reported faint tracks leading into the infamous Devil’s Maze. The couple, he concluded, had wandered in, become lost, and perished. The search was called off after two days.

Samuel protested. Elijah was an experienced geologist, equipped with maps, GPS, and survival gear. But Wilcox was unmoved. “My deputy is the best there is. He says they went into the maze, they went into the maze. Case closed.”

Eight Years of Silence

For Samuel, the years that followed were a study in grief and obsession. His wife’s death from illness only deepened his resolve. His study became a war room: satellite maps, geological surveys, newspaper clippings, and the thin official case file obtained through the Freedom of Information Act. One detail haunted him: Elijah’s mention of the “territorial” deputy. Samuel hired private investigators, made trips to Utah, and tried to speak with the reclusive prospector named in the original report. But he found only dead ends and a wall of local loyalty.

Meanwhile, Dale Lteran had ascended to sheriff, his wealth and land holdings growing mysteriously. Yet there was no proof of wrongdoing—only the certainty, in Samuel’s historian’s bones, that the truth had been buried.

The Desert Gives Up Its Dead

In late summer 2018, a Bureau of Land Management crew was sealing a collapsed silver mine near a desolate mesa. After blasting open the entrance, they found two skeletons, seated upright on an ore crate, dressed in the remains of modern hiking clothes. The tableau was too deliberate, too staged, to be accidental. The mine was a tomb.

Detective Kate Riley of the Utah Bureau of Criminal Investigation was assigned to the reopened case. She began not with the mine, but with the files. The original investigation, she found, was built on a single, uncorroborated opinion—Deputy Lteran’s. “Lost to the desert” was a conclusion, not a finding.

Riley called Samuel Sinclair. She promised no platitudes, only that she would follow the evidence wherever it led. For the first time in eight years, Samuel felt heard.

Unraveling the Lie

The mine was a time capsule. Forensic anthropologists confirmed the skeletons—identified by dental records as Elijah and Nia—had been posed after death. Natural decomposition would have left them slumped, not seated side by side. The mine entrance, geologists found, had been sealed by a deliberate, professional blast, not a natural collapse. The killer had both the knowledge and the arrogance to believe the tomb would never be found.

The cause of death, revealed by toxicology on bone samples, was acute arsenic poisoning—levels hundreds of times higher than any environmental exposure. This was not an accident or a slow accumulation, but a massive, single-dose ingestion. Poison, Riley knew, requires trust. The killer had handed the Sinclairs their deaths.

The investigation shifted. Arsenic, while present in the local geology, was also a byproduct of illegal gold and silver processing—an old prospector’s trick. The Sinclairs, with their expertise, could have recognized signs of illicit mining. The motive was now clear: greed, not misadventure.

The Red Herring

Riley returned to the architects of the original narrative. Wilcox, now retired, was defensive and dismissive. Lteran, now sheriff, was smooth and cooperative, pointing Riley toward the dead prospector Hemings as a likely suspect. A search of Hemings’ property uncovered arsenic and an illegal lab, bolstering the case against him. The local press ran with the story: the eccentric, dead recluse was the killer.

But Riley wasn’t convinced. The case was too neat. The arsenic matched, but Hemings had died four years earlier. The real break came from a different angle: explosives.

The Smoking Gun

Riley sent soil and rock samples from the mine entrance to the ATF lab. The residue was a match for commercial ditching dynamite and, crucially, a proprietary type of blasting cap used only by law enforcement and government agencies. A prospector like Hemings could never have obtained it.

Riley searched the sheriff’s department’s explosives inventory log from 2010. She found an entry, dated two days before the Sinclairs vanished: a case of ditching dynamite and a box of high-security blasting caps, signed out by Deputy Dale Lteran for “beaver dam removal” in another county. The chemical signature matched the mine.

Riley now had the final, unassailable link: the murder weapon, the motive, and the killer’s signature in official ink.

Justice at Last

Confronted with the evidence, Lteran’s mask slipped. He confessed: to the illegal mining operation, to poisoning the Sinclairs, to staging their bodies, and to sealing the mine. His only regret was being caught—not for the murders, but for the end of his perfect crime.

For eight years, Lteran had used his expertise and the trust of his community to orchestrate a murder and cover-up, exploiting the prejudices of his boss and the silence of the desert. The Sinclairs had not been lost to nature, but to human greed and racism.

A Final Reckoning

A month later, Samuel Sinclair stood at the now-permanently sealed mine, a bronze plaque marking it as a grave. Detective Riley handed him Elijah’s geology hammer, recovered from the tomb. “You gave him back his name,” Samuel said, tears in his eyes. “You gave them both back their dignity.”

The Utah desert, once a silent accomplice, had finally yielded its truth. The case of Elijah and Nia Sinclair stands as a stark reminder: sometimes, the greatest dangers are not the wilderness, but the people trusted to protect it. And sometimes, the truth, no matter how deeply buried, will find its way to the light.

News

Perfect Wife Slipped Her Husband Strong Sleeping Pill & 𝐂𝐚𝐬𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐝 Him For His Infidelity | HO

Perfect Wife Slipped Her Husband Strong Sleeping Pill & 𝐂𝐚𝐬𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐝 Him For His Infidelity | HO The bell finally rang….

”I’M SCARED! I’M SCARED!” — Neighbor Finds Woman 𝐋𝐨𝐜𝐤𝐞𝐝 In Kennel | HO

”I’M SCARED! I’M SCARED!” — Neighbor Finds Woman 𝐋𝐨𝐜𝐤𝐞𝐝 In Kennel | HO Here is the hinged sentence that snaps…

Antifa Bully Harasses Woman, Then Her HUSBAND Shows Up… | HO

Antifa Bully Harasses Woman, Then Her HUSBAND Shows Up… | HO And then it happens fast, the way these things…

Elvis Sang to His Daughter After Divorce — His Voice Cracked — She Asked ”Why Are You Crying?” | HO!!

Elvis Sang to His Daughter After Divorce — His Voice Cracked — She Asked ”Why Are You Crying?” | HO!!…

Chicago Mafia Boss Vanished in 1963 — 60 Years Later, His Cadillac Is Found Buried Under a Speakeasy | HO!!

Chicago Mafia Boss Vanished in 1963 — 60 Years Later, His Cadillac Is Found Buried Under a Speakeasy | HO!!…

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon – Found Hiding 4 Months Later Found Inside TREE’S Hollow, Whispering | HO!!

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon – Found Hiding 4 Months Later Found Inside TREE’S Hollow, Whispering | HO!! Here was…

End of content

No more pages to load