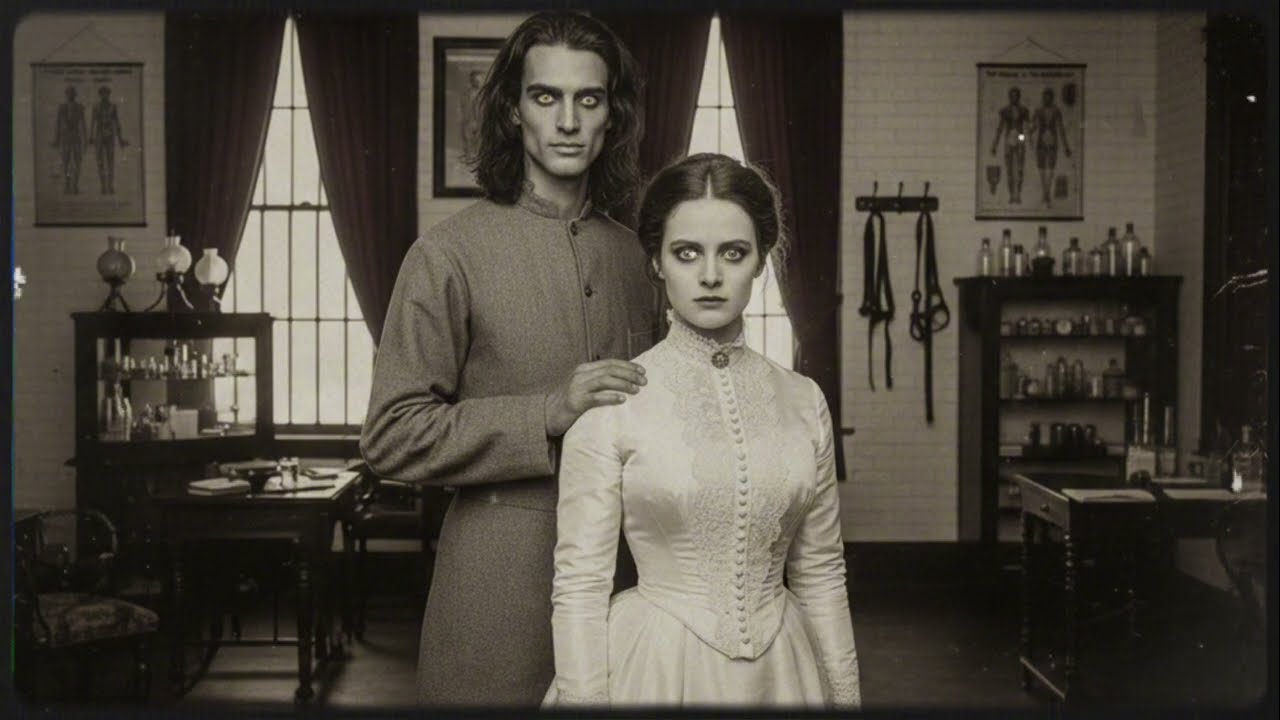

What Really Happened Between the Asylum Owner’s Wife and the Man He Called Insane? | HO

There are stories history tries to bury so deeply that even the descendants of those involved speak of them only in whispers. Stories so disturbing, so profoundly destabilizing to the myth of respectable society, that the truth remains sealed in archives for a century or more. Brattleboro, Vermont, is a quiet town now—picturesque, forest-ringed, built on traditions of New England restraint. But in the winter of 1867, before the age of modern psychiatry and long before conversations about mental health were even possible, it was home to a scandal that shocked the eastern seaboard.

On November 17th of that year, the basement of Blackwood Asylum became the stage for one of the most horrifying scenes in Vermont history. Blood steamed on cold stone floors. A respected physician lay butchered beyond recognition. A convicted murderer lay dead beside him. And in the center of it all sat Vivien Blackwood, the doctor’s wife, her white nightgown soaked with blood that was not hers, cradled in the arms of the man the state had labeled criminally insane.

When the night watchman found them, Vivien looked up calmly and said, “You’re early, Marcus. We weren’t quite finished.”

At the time, authorities believed they had uncovered the aftermath of a violent escape—an insane patient who had broken free, slaughtered the doctor, attacked his wife, and been shot dead in the struggle. It was tragic. Gruesome. But simple.

Except it wasn’t.

When sealed records were opened in 1967—including private journals, suppressed investigative notes, and correspondence Vermont’s officials had tried desperately to hide—a different picture emerged. One of manipulation, torture disguised as medicine, passion twisted into violence, and a woman who transformed herself from society bride to one of the most terrifyingly calculated killers in New England’s history.

This is the true story—as complete as modern historians can piece together—of what really happened between Vivien Blackwood and Thomas Crane, the man her husband called insane.

It does not begin with murder.

It begins with a wedding.

-

A Bride Sold to the Highest Status

September 14th, 1865. Burlington, Vermont. The air was crisp, the leaves a riot of scarlet and gold, and St. Paul’s Cathedral overflowed with the state’s elite. By all appearances, it was a perfect autumn wedding. A wealthy lumber baron giving away his only daughter. A respected physician, Dr. Henry Blackwood, taking a bride who would elevate his social position. Two powerful families merging their legacies.

Inside the cathedral’s preparation room, Vivien Marie Sutherland stared into a gilded mirror. The reflection showed a flawless bride—porcelain skin, elaborate curls pinned with pearls, a lace gown imported from Paris. But behind the beauty, behind the perfect posture her mother had drilled into her since childhood, hid something colder. Something resigned. Something hollow.

Her mother adjusted the veil with trembling hands.

“Dr. Blackwood is a fortunate man,” she said.

Vivien did not respond. What could she say? She barely knew the man she was about to marry. Their courtship consisted of six supervised visits in drawing rooms, each filled with Henry’s long monologues about brain anatomy, hysteria, and the “biological limitations of the female mind.” He had never once asked her opinion. Never asked about her interests. Never asked about her fears.

He examined her with the same fascination he reserved for the surgical instruments displayed in his study.

Yet her father approved. Henry came from old money, owned Vermont’s largest psychiatric institution, and had influence in medical and political circles. He was, according to Andrew Sutherland, “a suitable husband.”

At the altar, Vivien repeated vows that tasted like dust. She felt herself splitting—part obedient daughter performing her expected role, part silent observer trapped behind her own eyes, analyzing her future with a chilling detachment.

After the celebration, after the toasts and speeches, after the carriage ride to Henry’s estate, she entered a world colder than the Vermont winter.

A world of locked doors.

A husband who treated her as a decorative object.

And an asylum where the boundaries of morality had already begun to rot.

-

The Marriage That Was Really a Prison

The Blackwood estate was enormous—three stories of federal-style stone, twelve bedrooms, manicured gardens. A mansion meant to impress. But inside, the air felt perpetually cold, as if the warmth of human emotion had been bled out of the walls.

Henry showed her to her private suite of rooms. “We will maintain separate quarters,” he said. “I require privacy for my work.”

They shared a bed only three times in six months, and each time Henry performed his “marital duty” with the mechanical disinterest of a man filing paperwork.

He ate alone.

He worked alone.

He spoke to her only about schedules, upcoming charity events, or household business.

When Vivien attempted conversation, Henry deflected with lectures about hysteria, the fragility of female nerves, and his latest theories in psychiatric intervention.

He was not cruel in the overt sense.

He was something worse: indifferent.

Vivien took long walks through the forested grounds, her breath fogging in the air, trying to feel something. Anything. But inside, something else was growing—a presence, a watcher, a version of herself she barely recognized. A version that did not fear Henry, but resented him. Studied him. Calculated.

Then, one rainy evening, she overheard something that shattered whatever remnants of loyalty she had tried to cultivate.

Standing outside his study door, she heard Henry speak to a colleague.

“The female temperament is inherently unstable. Even my wife demonstrates concerning tendencies—excessive reading, solitary walks in bad weather. If she were not my wife, I would consider her an ideal subject for controlled psychiatric intervention.”

The colleague laughed.

“Why not use her? Scientific progress begins at home.”

“Don’t tempt me,” Henry replied.

Vivien stood dripping rainwater, heart hammering, and felt something inside her snap.

She realized she was not a wife.

She was a specimen.

And if Henry viewed her as material for experimentation, then she had only one option:

Destroy him before he destroyed her.

III. The Asylum and the Man in the Cell

Vivien asked to tour the asylum under the guise of charity. Henry, pleased with her “interest,” agreed.

Blackwood Asylum was imposing—four stories of brick, iron-barred windows, and a surrounding fence that resembled a fortress. The first floors were filled with patients embroidering quietly or reading under supervision. These were the rooms Henry proudly showed donors.

But the fourth floor?

That was where the truth lived.

The secure wing.

A corridor of white walls, chemical stench, and voices echoing in a way that made Vivien’s skin prickle. Screams traveled faintly through the ventilation, vibrating the air.

Henry led her to the final cell at the hall’s end.

He seemed almost excited.

“This is our most interesting case,” he announced.

Vivien saw a man sitting on his cot, reading.

Twenty-eight years old, dark hair falling past his shoulders. Eyes like amber catching fire in the afternoon light. Too alert. Too intelligent. Far too present to belong in a cage.

“Thomas Crane,” Henry said. “Diagnosed with moral insanity. Killed three men in Boston. His family paid for lifelong commitment to avoid scandal.”

Vivien asked, “Why did he kill them?”

Before Henry could answer, Thomas spoke.

“They were planning to murder my friend. I acted first.”

Henry scoffed. “Delusions of rationalization. He cannot comprehend morality.”

Thomas rose and stepped toward the bars. His gaze locked on Vivien with such intensity that she momentarily forgot how to breathe.

“I comprehend perfectly,” he said. “I simply reject your husband’s definition of sanity.”

Henry snapped, “Enough. Increase his sedation. He’s becoming agitated.”

But Thomas was not agitated.

He was studying her.

As she left the corridor, he called out softly:

“You’re awake, Mrs. Blackwood. The others sleep, but not you.”

That night, lying awake in her cold bed, Vivien realized something terrifying:

For the first time since her marriage, someone had truly seen her.

-

Conversations Through Bars

Vivien began visiting the asylum weekly, then twice weekly, under the guise of charity. Most of the staff admired her gentleness, her grace, her sympathy.

But her real destination was always the same:

the fourth-floor cell at the end of the corridor.

Her conversations with Thomas were unlike anything she’d ever experienced. He asked about her thoughts, her dreams, her fears. He spoke to her not as an ornament, not as a fragile creature, but as an equal.

An equal with teeth.

One evening, he said quietly, “Your husband tortures people in the basement.”

Vivien recoiled, but Thomas continued.

“I hear the screams through the vents. Many who go down there never come back up.”

She wanted to believe he was lying, but she knew better. Henry’s journals, which she later picked open with trembling hands, confirmed it all.

Unanesthetized cranial operations.

Isolation torture.

Electrical experiments.

Patients buried in unmarked graves.

Henry Blackwood was not a doctor.

He was a collector of suffering.

Vivien returned to Thomas with the journals fresh in her mind.

“Why tell me?” she whispered.

Thomas smiled, slow and devastating.

“Because you’re capable of understanding me. Because you’re capable of anything.”

Their relationship darkened. Deepened. Merged two forms of brokenness into something potent and dangerous.

It was not love.

It was recognition.

Two prisoners.

Two predators in cages.

Two people who knew what it meant to be underestimated, controlled, dismissed.

And then one day, Vivien asked the question that sealed their fate:

“If I helped you escape… would you help me end this?”

Thomas did not hesitate.

“Yes.”

-

The Plan

The murder of Henry Blackwood was not spontaneous. It was not desperate. It was not a violent eruption of insanity.

It was choreographed.

Vivien spent eight months preparing:

studying guard rotations

duplicating keys

smuggling clothes to Thomas

ingratiating herself with staff

memorizing every blind spot in the asylum

planning an alibi

preparing a narrative investigators would accept

choosing the exact night Henry would die

And as the weeks passed, something else happened—something darker.

Three new patients admitted to the asylum died shortly after under mysterious circumstances. Two women, one man. Each death labeled natural. Each later revealed, through suppressed autopsy notes, to have been the result of subtle poisoning or carefully induced respiratory failure.

Practicing.

Preparing.

Learning.

Vivien documented the process in her private journal:

“I must know what death looks like. I must know how to conceal it.”

-

The Night Everything Burned

November 17th, 1867.

Snow thick in the air, cold enough that breath turned to frost.

Henry descended to the basement laboratory at 8 p.m. to begin his weekly “research.” Vivien arrived later with a basket of Christmas ornaments, smiling sweetly at guards who barely glanced at the doctor’s philanthropic wife.

At midnight, she unlocked Thomas’s cell.

“Last chance to walk away,” he whispered.

“I walked away from the person I used to be the day I married him,” she replied.

Together they moved like shadows.

Henry worked in the basement, preparing to operate on a sedated young woman named Sarah Miller—a patient committed for “hysteria” after becoming pregnant out of wedlock. Vivien recognized her from the women’s ward.

She was barely breathing.

When Henry turned and saw his wife standing beside the escaped prisoner, his face flickered through stages of confusion, shock, fear.

“Vivien… what are you—?”

“Conducting an experiment,” she said. “On you.”

She smiled.

VII. The Killing of Dr. Henry Blackwood

The murder was not fast.

It was not chaotic.

It was not the frenzy the newspapers described.

It was deliberate.

Henry was strapped to his own examination table. He begged. He promised. He wept. He swore he would free her, reform the asylum, give her anything she wanted.

Thomas held him down. Vivien retrieved the instruments.

They used Henry’s tools: scalpels, clamps, electrical devices meant for “corrective therapy.”

Vivien made the first incision.

Henry screamed, but the walls were soundproof.

For three hours, they did to Henry precisely what he had done to dozens:

They studied his fear.

His pain.

His helplessness.

Vivien asked clinical questions during the process.

“Does the terror sharpen before the heart rate increases?”

“When does the mind begin to detach from the body?”

“How long until the will breaks?”

Thomas marveled at her composure.

“You’re magnificent,” he whispered.

At 3:16 a.m., Henry Blackwood died.

Vivien looked down at his ruined face and felt nothing.

Not guilt.

Not joy.

Not relief.

Just freedom.

VIII. The Final Betrayal

Thomas turned to her, still breathing hard from exertion.

“We must go,” he said. “The staff will come soon. I’ve planned our escape route.”

But Vivien was no longer the caged woman he had rescued.

She was something else now.

She picked up Henry’s pistol.

Thomas’s expression shifted—not fear, but understanding.

“You’re going to blame this on me.”

“Yes,” she said softly. “Dead, you give me a perfect alibi. Alive, you’re a liability.”

He smiled—the same devastating smile she had first seen through bars.

“You really are perfect.”

She shot him in the chest.

Then the head.

Marcus Webb, the night watchman, arrived seconds later and saw the scene exactly as Vivien intended:

A butchered doctor.

A woman soaked in blood.

A notorious killer dead on the floor.

A pistol in the trembling hands of the grieving wife.

“You’ll say what I tell you to say,” she instructed.

And Marcus, terrified and shaking, agreed.

-

The Cover-Up

The investigation was swift, neatly concluded, and deeply flawed.

Authorities accepted Vivien’s version instantly:

Thomas Crane escaped.

Killed Dr. Blackwood in a deranged attack.

Turned on Vivien.

Was shot in self-defense.

Simple.

Satisfying.

Wrong.

The asylum’s basement laboratory revealed horrors lawmakers did NOT want public:

nine bodies buried in unmarked graves

evidence of illegal experiments

torture chambers disguised as medical rooms

journals documenting procedures that would later be recognized as war crimes in other contexts

Doctors from Boston and New York had visited the asylum, knew the truth, and supported Henry’s work. Powerful men. Influential men.

They needed the scandal contained.

Vivien needed the scandal redirected.

Their goals aligned.

The records were sealed.

The graves were moved.

The journals were locked away until 1967.

The visiting doctors’ names were redacted.

The official story stood for 100 years.

-

The Widow Who Became Untouchable

Vivien wore mourning black for six months. She wept publicly, donated to charities, spoke eloquently of “tragic loss.”

She inherited Henry’s entire estate—money, land, investments—and sold the asylum to a group of physicians who promised reform.

Six years later, the institution mysteriously burned to the ground.

Vivien lived quietly, deliberately, elegantly.

And people around her began dying.

Her father “fell” down the stairs weeks after she learned he was arranging a second marriage for her.

Henry’s assistant died of “heart failure” after questioning her version of events.

Three nurses died under suspicious yet explainable circumstances.

Marcus Webb drank himself to death—unable to reconcile the woman the public worshipped with the killer he’d seen.

By the time Vivien died peacefully in her sleep in 1918 at age 73, she was celebrated as a philanthropist, an advocate for mental health, and one of Vermont’s greatest benefactors.

Her funeral was attended by the governor, senators, and hundreds of people whose lives she had touched.

No one suspected the truth.

-

The Journal That Revealed Everything

After Vivien’s death, her personal journals were locked away by the family. It was not until 1967—when Vermont law required the unsealing of certain historical documents—that her writing finally emerged.

The final entry, written the night before she died, shook researchers, criminologists, and psychologists to their core:

“The world divides people into victims and monsters. But that division is false. We are all both.

I chose to be a monster disguised as a victim.

And that, I discovered, is the most powerful role of all.”

She named everyone she had killed.

She explained each method.

She detailed her reasoning.

She accepted no guilt.

No remorse.

Only clarity.

Vivien Blackwood had not snapped.

She had not been corrupted by Thomas Crane.

She had not been radicalized by torture.

She had simply stopped pretending.

XII. So What Really Happened Between Vivien Blackwood and Thomas Crane?

Not love.

Not insanity.

Not seduction.

Recognition.

Two intelligent, imprisoned people—one physically caged, one socially and legally caged—found in each other a mirror.

He awakened her.

She perfected what he began.

And in the end, she killed him because he was the last remaining witness to the truth:

She was not his creation.

She was not his accomplice.

She was not his partner.

She was his successor.

A predator who learned that society will always trust a beautiful widow over a convicted criminal.

A woman who understood that the performance of innocence is the greatest weapon of all.

A killer who lived fifty more years without being suspected once.

Conclusion: The Most Dangerous Monsters Wear Masks

“What really happened between the asylum owner’s wife and the man he called insane?”

Everything society feared.

Everything society refused to see.

Everything society still struggles to understand.

A brutalized woman found her freedom.

A manipulative genius met an equal.

A corrupt doctor faced justice in the only form he understood.

And Vermont produced one of the most chilling female criminals in American history.

Vivien wasn’t a victim who snapped.

She was a woman who discovered her power.

A woman who learned that performance can hide anything.

A woman who used society’s expectations as weapons.

The greatest monsters are never the ones locked in cages.

The greatest monsters are those who know how to act like they don’t belong there.

News

Appalachian Hikers Found Foil-Wrapped Cabin, Inside Was Something Bizarre! | HO!!

Appalachian Hikers Found Foil-Wrapped Cabin, Inside Was Something Bizarre! | HO!! They were freelance cartographers hired by a private land…

(1879) The Most Feared Family America Tried to Erase | HO!!

(1879) The Most Feared Family America Tried to Erase | HO!! The soil in Morris County held grudges. Settlers who…

My Son’s Wife Changed The Locks On My Home. The Next Morning, She Found Her Things On The Lawn. | HO!!

My Son’s Wife Changed The Locks On My Home. The Next Morning, She Found Her Things On The Lawn. |…

22-Year-Old 𝐁𝐫𝐮𝐭𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐊*𝐥𝐥𝐬 40-Year-Old Girlfriend & Her Daughter After 1 Month of Dating | HO!!

22-Year-Old 𝐁𝐫𝐮𝐭𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐊*𝐥𝐥𝐬 40-Year-Old Girlfriend & Her Daughter After 1 Month of Dating | HO!! In those first days, Javon…

12 Doctors Couldn’t Deliver the Billionaire’s Baby — Until a Poor Cleaner Walked In And Did What…. | HO!!

12 Doctors Couldn’t Deliver the Billionaire’s Baby — Until a Poor Cleaner Walked In And Did What…. | HO!! Her…

It Was Just a Family Photo—But Look Closely at One of the Children’s Hands | HO!!!!

It Was Just a Family Photo—But Look Closely at One of the Children’s Hands | HO!!!! The photograph lived in…

End of content

No more pages to load