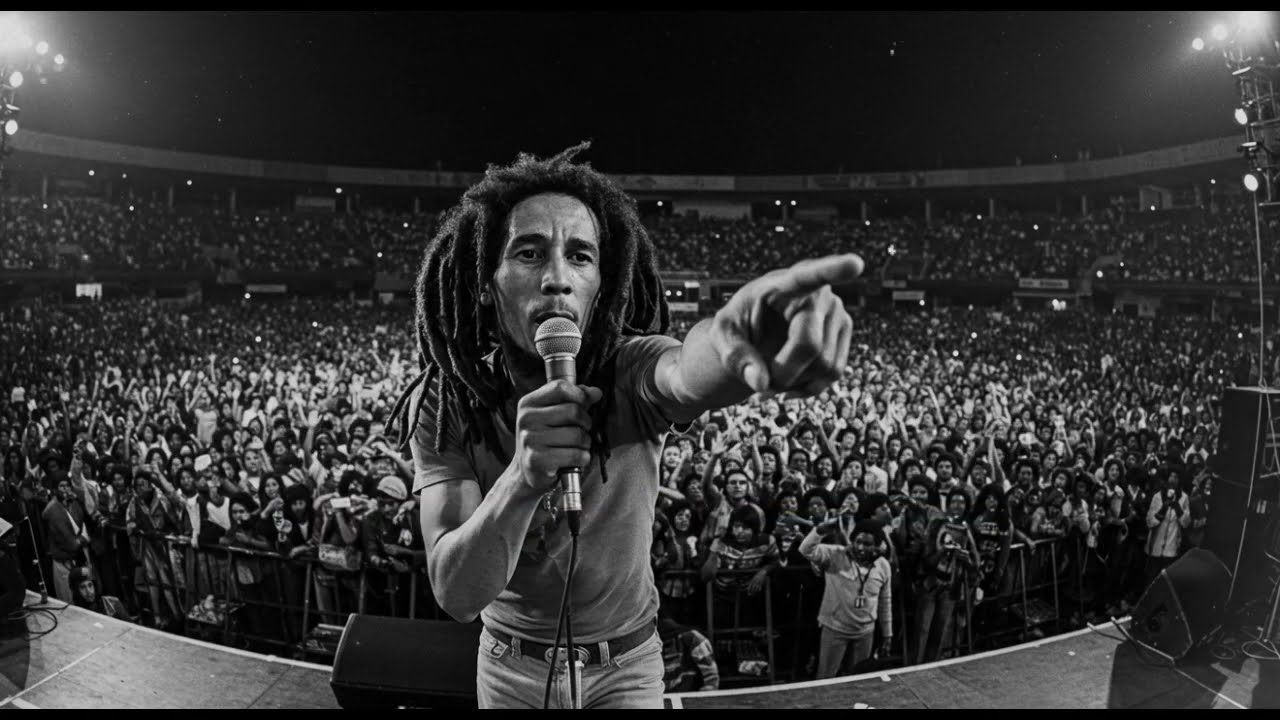

White sᴜᴘʀᴇᴍᴀᴄɪsᴛ Tried to ATTACK Bob Marley on Stage — What Bob Did Made 15,000 People CRY | HO!!!!

Part I — The Plan

Oakland, California.

June 7, 1979. 7 p.m.

The parking lot outside the Oakland Coliseum pulsed with life—thousands of people streaming toward the arena under a sky the color of copper. The smell of weed, sweat, and anticipation hung thick in the air. Inside his pickup truck, twenty-eight-year-old Derek Mitchell gripped the steering wheel so tightly his knuckles went white.

He wasn’t here for the music.

He was here to make a statement.

For three weeks he had planned this. The signs were folded neatly in the truck bed: slogans painted in red and black, Confederate flags rolled tight like weapons. He and five members of his white-supremacist group had sworn this would be the night they exposed Bob Marley—this “drug-promoting, race-mixing Rasta preacher”—and drove him out of their city.

Derek had grown up in the timber country of rural Oregon, son of a logger who taught him that “the world has an order.” By his teens he’d absorbed every lie about blood and hierarchy. By twenty he was marching with hate groups, fists raised. Violence gave him belonging; ideology gave him purpose.

Now he was about to aim that purpose at one man.

But there was a problem Derek hadn’t calculated: to be close enough to rush the stage, he had to sit among the people he hated.

Part II — The Crack

He found himself in the third row—close enough to see the sweat on the microphones, close enough to smell the incense drifting from backstage. Around him sat the faces of everyone his group despised: Black, white, Latino, Asian—families, lovers, college kids laughing in shared excitement. The energy was disarming, almost holy.

Why are they smiling? he thought. Don’t they know?

As the lights dimmed, a roar rolled through the arena. And then Bob Marley walked out.

Photographs had never captured it. The man radiated something that felt less like fame and more like faith—barefoot, dreadlocked, eyes shining like he saw a different world entirely. The band struck the first chords of “Positive Vibration.” The floor trembled. Fifteen thousand voices rose as one.

Derek stayed seated, arms crossed, the banner heavy inside his jacket. But each song worked on him like water on stone. Joy was contagious—and he felt himself catching it against his will.

Then Bob spoke.

“They want you to believe we are enemies,” he said, voice ringing through the rafters. “Black and white, rich and poor—divided people are easy to control. But I tell you the truth: we are one people, one love, one heart.”

Something in Derek shifted, small but undeniable. He clenched his fists, whispering the slogans he’d memorized. But the music kept coming.

“War.” Bob’s thunderous adaptation of Haile Selassie’s UN speech hit like scripture.

Until the philosophy which holds one race superior and another inferior is finally and permanently discredited and abandoned—everywhere is war.

Each line struck him harder. Until the color of a man’s skin is of no more significance than the color of his eyes…

Around him, strangers of every color sang those words together. Derek tried to hang on to his anger—and felt it slipping.

Part III — The Stare

By the time Marley launched into “Exodus,” Derek knew this was the signal. He was supposed to stand, wave the flag, call his men forward. But when he rose, his body refused to move.

And then Bob looked at him.

Fifteen thousand people—and yet somehow Marley’s eyes found the one man in the third row who wasn’t moving. They locked. Derek froze, heart hammering. The band played on. The crowd swayed. Bob’s gaze didn’t waver.

No anger. No fear. Just recognition.

Then, mid-verse, Bob changed the lyric.

“Brother, you’re running and you’re running and you’re running away,” he sang, pointing directly at Derek. “But you can’t run away from yourself.”

The crowd turned to see who Bob was singing to. Derek wanted to disappear, but Bob kept singing, eyes never leaving his.

“Brother, you’re running away… but you can’t run away from yourself.”

And then he smiled. Not mockery—mercy. The kind of smile that disarms every weapon.

Something broke.

Derek Mitchell began to cry.

Right there, in front of his friends, in front of fifteen thousand people, in front of the man he’d come to destroy.

Part II — The Breaking Point

The horns blasted the bridge of Exodus, but Derek heard nothing except his own heartbeat.

Bob Marley’s voice wrapped around him like a prayer.

When the final chorus ended, the crowd exploded into motion again—hands raised, bodies swaying—but Derek stayed frozen, tears rolling down a face that had forgotten how to feel.

The Black father beside him leaned over, resting a hand on his shoulder.

“You all right, brother?” he asked.

That word—brother—hit harder than the music.

Derek shook his head. “No,” he whispered. “I don’t think I’ve ever been all right.”

The man didn’t press. He just gave a small squeeze. “Music has a way of reaching the places we keep hidden,” he said. “Let it work on you.”

For the rest of the concert, Derek sat there trembling, letting it work.

When Marley sang “One Love,” Derek sang along through tears.

When “Redemption Song” began—Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery; none but ourselves can free our minds—he felt something deep inside of him split open.

He realized he’d been enslaved all along, not by chains but by ideology—by fear masquerading as power.

And in that moment, Derek Mitchell chose to be free.

The Parking Lot

After the lights came up, Derek’s friends found him sitting on the curb, head in his hands.

“What happened, man?” one hissed. “You were supposed to give the signal! We were ready to go!”

Derek looked at them—men who had been his family, his mirror, his cage.

“I can’t do this anymore,” he said.

“Can’t do what?”

“This. The hate. The anger. I can’t carry it anymore.”

They stared at him, half-shocked, half-furious.

“You’re weak,” one spat.

Derek stood up slowly. “Don’t say that word around me again.”

They walked away, leaving him alone in the flickering orange of the parking-lot lights.

He drove home in silence, rolled his Confederate banners into a box, and threw them in a dumpster behind a grocery store.

For the first time in his life, he felt both lost and clean.

The Church

The next Sunday he showed up at a small Black church in East Oakland.

He didn’t know why. Maybe because Bob’s lyrics had sounded like sermons. Maybe because he wanted to see if grace was real.

When he walked in, conversations stopped. Every eye turned.

A white man with tattoos of eagles and lightning bolts across his arms didn’t exactly blend in.

The pastor, Reverend James Washington, stepped down from the pulpit and met him halfway up the aisle.

“What brings you here, son?”

Derek’s voice cracked. “I’m not sure. Maybe forgiveness.”

Washington studied him for a long moment, then nodded. “Then you came to the right place. Sit down. We’ll start there.”

The Unlearning

Over months, then years, Derek rebuilt himself from the ground up.

He volunteered in food drives, repainted classrooms, listened more than he spoke.

He read Scripture beside men whose grandparents he’d been taught to hate.

Each act of kindness chipped away another layer of rust.

When he finally told his story to the congregation—how he’d gone to the Bob Marley concert to attack, how the music and one man’s compassion had undone him—no one jeered.

They cried.

Reverend Washington put a hand on his shoulder.

“Son, redemption isn’t something you earn. It’s something you accept. Bob showed you love when you came with hate. Now learn to show yourself the same love.”

Letters and Legacy

Three years later, Derek wrote a letter to Bob Marley’s management:

“I was the man in the third row in Oakland.

I came to silence him.

He sang instead.

And his song saved me.”

He never knew if Marley saw it.

By then, the singer was already sick with cancer.

Within a year, Bob Marley was gone.

But Derek’s new life had only begun.

By the mid-1980s, he was working with youth outreach programs, focusing on kids pulled into hate groups.

By 1990, he was standing in front of schools and churches, telling his story—the story of the night he went to destroy Bob Marley and ended up destroyed by love.

Over the next decade he helped pull more than two hundred young people out of extremism.

When asked how he did it, he’d always say, “I don’t argue. I listen. The truth that saved me came through a song, not a fist.”

The Pilgrimage

In 2001, on what would have been Bob Marley’s fifty-sixth birthday, Derek flew to Jamaica.

He stood before Marley’s mausoleum in Nine Mile, hands trembling, eyes full.

“I came to kill your message,” he whispered. “But your message killed the hate in me instead.”

He left a single rose and the ticket stub from that night in 1979—faded, creased, sacred.

Part III — Forty Years Later

Oakland Coliseum, June 7, 2019.

Exactly forty years to the day.

The arena looked different now—renovated seats, new lights, digital screens—but the air carried the same pulse. The crowd was there for a Bob Marley tribute concert, and before the band began, the emcee stepped to the mic.

“Tonight,” he said, “we have a guest with a story you’re going to remember.”

From the wings walked a white-haired man in a simple black suit, walking cane in one hand. Some in the audience clapped politely, not knowing who he was. Others recognized the name and rose to their feet.

Derek Mitchell.

The man who once tried to destroy Bob Marley’s concert.

Now seventy-three years old, standing on the same stage he had once meant to storm.

He looked out at the sea of faces—Black, white, brown, young, old—all swaying together to the reggae groove that played softly beneath his entrance. For a long moment he just breathed, his eyes glistening.

The Confession

“I came to this arena forty years ago,” he began, voice low but clear, “a man full of hate. I left a man full of questions.”

The audience quieted instantly. Even the band stopped.

“I had a plan that night,” Derek continued. “I thought if I could embarrass Bob Marley, I’d prove something—to my friends, to my beliefs, maybe to myself. But Bob Marley didn’t embarrass me. He saw me.”

He paused, swallowing hard. “He looked straight into my eyes, and instead of hate, he gave me love. I didn’t deserve it. But he gave it anyway.”

His voice cracked on the last word. The crowd leaned forward, hundreds wiping their eyes.

The Realization

Derek went on to describe what happened after: the sleepless nights, the church, the years of rebuilding, the foundation he founded to help kids escape hate groups. “I used to think the opposite of hate was tolerance,” he said. “But it’s not. The opposite of hate is understanding.”

He reached into his pocket and pulled out a small, weathered object—a concert ticket stub, faded and brittle.

“This is from that night,” he said softly. “I keep it to remind me that one song, one moment, can save a life.”

Behind him, the tribute band began to play the first notes of ‘One Love.’

The crowd rose instinctively, thousands of voices singing the chorus.

One love, one heart, let’s get together and feel all right…

Derek turned to listen, tears running freely down his face.

The Message

When the music softened, he faced the audience again.

“Bob Marley taught me something that night,” he said. “We’re all running from something—pain, fear, shame. We build walls and ideologies to protect ourselves from what’s inside us. But music, real music, breaks those walls. It makes you feel what you’ve been hiding.”

He wiped his eyes, smiling. “Love isn’t weakness. Love is the most revolutionary force that exists.”

He paused, letting the words sink in. “That’s what Bob understood. It’s what he lived. And it’s what he gave to a man who came to hurt him.”

The arena was silent. Then, one by one, people began to stand. Applause swelled—not wild, but reverent. A standing ovation that felt like forgiveness.

Derek closed his eyes and whispered into the mic, “Thank you, Bob.”

The Aftermath

That speech went viral. Millions watched the clip online. Students wrote essays about it. Teachers used it in classrooms about empathy and racial reconciliation. Derek’s foundation, One Love Redemption, expanded nationally.

When journalists asked why he thought Bob’s message still resonated, Derek would smile. “Because truth doesn’t age. We’re still learning to love each other.”

On his office wall hung that original 1979 poster—creased, sun-bleached, edges torn. Beneath it was a framed line handwritten on paper:

Brother, you can’t run away from yourself.

He’d written it out in Bob Marley’s words as a daily reminder that transformation starts within.

The Legacy

Before every lecture, Derek would tell young audiences, “Don’t let anyone convince you that hate is power. It’s not. Hate is fear pretending to be strength. Real power is when you can look at someone you don’t understand and call them brother.”

He told the story so many times he could have recited it in his sleep, but it never lost its weight. Because every time he told it, someone in the crowd changed the way he once had—suddenly realizing that the enemy they’d imagined was human too.

The Final Return

Two years later, Derek visited Jamaica for the first time. He stood before Bob Marley’s mausoleum in Nine Mile, surrounded by the smell of earth and ganja and incense. He laid a single white rose on the stone.

“I came to destroy you,” he whispered. “And you destroyed my hate instead.”

He stayed for hours, praying, singing quietly to himself, the same line over and over: Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery.

When he finally turned to leave, a local musician sitting nearby began to strum a guitar. Without planning it, they both started singing ‘Redemption Song’ together. Two strangers, two different worlds, one voice.

Epilogue — The Man in the Third Row

Most people who were in that 1979 audience don’t remember the man Bob pointed at. There’s no official footage, no newspaper clipping, no viral photograph. But for Derek Mitchell—and for every life he touched afterward—that invisible moment became a monument.

Because that night in Oakland, 15,000 people witnessed something stronger than confrontation. They saw hate meet grace—and lose.

Derek likes to say it this way:

“Bob Marley didn’t save me with a sermon. He saved me with a song.”

He pauses, always the same way, letting the words breathe.

“He looked at me and saw not an enemy, but a brother. And once someone sees you like that, you can never unsee yourself.”

The crowd always stands. Always cries. Always sings along as the band fades in behind him:

One love, one heart…

And somewhere, if you listen close enough, you can almost hear Bob Marley’s voice echo back across forty years—soft, steady, smiling—

Let’s get together and feel all right.

News

When Your Friend 𝐃𝐢𝐬𝐞𝐦𝐛𝐨𝐰𝐞𝐥𝐬 You To Steal Your Unborn Child | HO!!

When Your Friend 𝐃𝐢𝐬𝐞𝐦𝐛𝐨𝐰𝐞𝐥𝐬 You To Steal Your Unborn Child | HO!! In the early 2000s, the Franklin family was…

He Took A Loan Of $67K For Their Baby shower, He Discovered that It Was A Scam, There Was No Baby &- | HO!!

He Took A Loan Of $67K For Their Baby shower, He Discovered that It Was A Scam, There Was No…

Billionaire Married a 𝐅𝐚𝐭 Girl For a Bet of 5M $ But Her Transformation Shocked Him! | HO!!

Billionaire Married a 𝐅𝐚𝐭 Girl For a Bet of 5M $ But Her Transformation Shocked Him! | HO!! One I…

I acted like a poor and naive mother when I met my daughter-in-law’s family — it turned out that… | HO!!!!

I acted like a poor and naive mother when I met my daughter-in-law’s family — it turned out that… |…

Why Did Louisiana’s Most Dangerous Slave Let Two White Women Into His Bed on the Same Night? | HO!!!!

Why Did Louisiana’s Most Dangerous Slave Let Two White Women Into His Bed on the Same Night? | HO!!!! November…

Husband Walks Out During Family Feud – What His Wife Did Next Made Steve Harvey LOSE IT | HO!!!!

Husband Walks Out During Family Feud – What His Wife Did Next Made Steve Harvey LOSE IT | HO!!!! Every…

End of content

No more pages to load