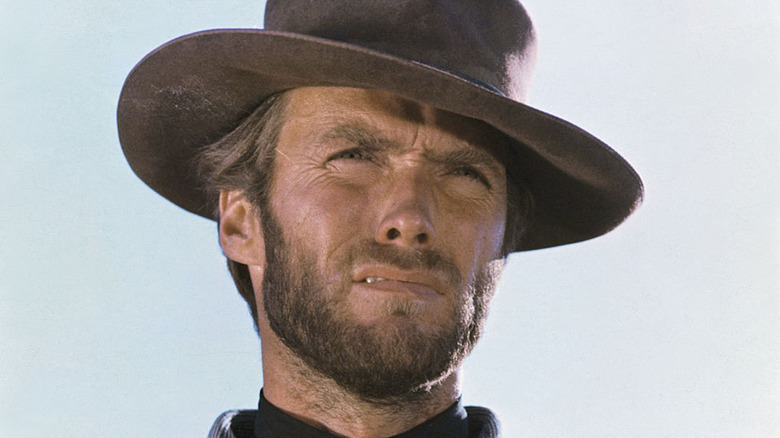

Why Clint Eastwood Never Dare Watch This Episode He Filmed in 1970 | HO!!!!

Clint Eastwood is, by any measure, a towering figure in American cinema. He is the rare artist who has left an indelible mark both in front of and behind the camera, his career spanning more than six decades and encompassing some of the most iconic roles and films in Hollywood history.

From the silent, steely-eyed gunslinger to the Oscar-winning director, Eastwood’s legacy is one of relentless reinvention and artistic risk. Yet, buried deep within his vast filmography lies a single work—a 1970 western adventure—that Eastwood himself has reportedly refused to ever watch again. The reasons, shrouded in creative conflict and personal discomfort, tell a story as fascinating as any of his films.

From Humble Beginnings to Hollywood Titan

Born Clinton Eastwood Jr. on May 31, 1930, in San Francisco, Eastwood’s early years were shaped by hardship. The Great Depression forced his family to move frequently as his father searched for work, instilling in young Clint a quiet resilience and formidable work ethic.

Long before the red carpets and Oscar speeches, he was a lumberjack, a gas station attendant, and later, a U.S. Army draftee during the Korean War. It was during his service at Fort Ord that Eastwood first encountered aspiring actors and began to sense the magnetic pull of performance.

His breakthrough came in the late 1950s with the television series Rawhide, where he played Rowdy Yates. The role was a stepping stone, but it was his portrayal of the enigmatic “Man with No Name” in Sergio Leone’s Dollars Trilogy—A Fistful of Dollars (1964), For a Few Dollars More (1965), and The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly (1966)—that launched him into international superstardom. The spaghetti westerns redefined the genre and cemented Eastwood as the ultimate anti-hero: cool, tough, and enigmatic.

He would go on to iconic roles in the Dirty Harry series, delivering the immortal line, “Go ahead, make my day,” and further solidifying his status as a symbol of American masculinity. But Eastwood was never content to remain just an actor. By the early 1970s, he was itching to direct and control his own creative destiny.

The Film He’d Rather Forget

Yet, just as his career was reaching new heights, Eastwood agreed to star in Two Mules for Sister Sara (1970), a film that would become a rare blemish—and a source of lasting discomfort—for the actor. The film, directed by Don Siegel, paired Eastwood with Shirley MacLaine in a western adventure that seemed, on paper, to be a perfect fit for his talents. He played Hogan, a skeptical mercenary who teams up with a mysterious nun, Sister Sara, played by MacLaine, on a dangerous journey through Mexico.

But from the very first days of filming, things went awry. Eastwood, known for his minimalist, instinct-driven approach, immediately clashed with MacLaine, whose acting style was assertive, dramatic, and often unpredictable. What began as creative tension soon escalated into frequent arguments and a strained working relationship. Years later, Eastwood would describe the experience as one of his most unpleasant on set, citing MacLaine’s confrontational style as a constant source of stress.

The problems didn’t end there. Eastwood was also deeply dissatisfied with the film’s tone and direction. Siegel, who would later become a frequent collaborator, tried to blend traditional western grit with quirky humor and plot twists. For Eastwood, the result was a muddled narrative that lacked the moral complexity and toughness he preferred. The film’s big reveal—that Sister Sara was not a nun at all, but a prostitute in disguise—struck Eastwood as forced and emotionally hollow.

Perhaps most importantly, Two Mules for Sister Sara represented a transitional period in Eastwood’s career. He was still a hired gun for the studios, working under directors and producers who did not fully understand or appreciate his creative instincts. Watching the film, he once admitted, would only remind him of those frustrations and compromises—a chapter he would rather leave closed.

The Unspoken Silence

Unlike his other westerns, which Eastwood has celebrated and discussed in countless interviews, Two Mules for Sister Sara is conspicuously absent from his retrospectives. He has rarely commented on the film, and when he has, his remarks have been terse and unenthusiastic. For a man who has always approached his work with a craftsman’s pride, this silence speaks volumes.

Sources close to Eastwood suggest that the experience left a deep mark. “Clint’s always been about control—about making the film he wants to make,” one longtime collaborator confided. “That movie was the opposite. It was compromise after compromise, and it just didn’t sit right with him.”

Behind the Scenes: Creative Conflict

The set of Two Mules for Sister Sara was reportedly a hotbed of creative conflict. MacLaine, already an established star, was outspoken about her own vision for the character, often challenging both Siegel and Eastwood. The two actors’ opposing styles—Eastwood’s quiet intensity versus MacLaine’s theatrical dynamism—created a palpable tension that seeped into every frame.

According to crew members, some scenes required dozens of takes, with MacLaine pushing for emotional nuance and Eastwood growing increasingly frustrated. “It was like oil and water,” recalled one former assistant director. “You’d see Clint just wanting to get through the scene, while Shirley wanted to explore every possible angle. It was exhausting.”

The director, Don Siegel, tried to mediate, but the damage was done. The film’s tone veered wildly between comedy and drama, and neither lead seemed satisfied with the final product.

A Transitional Moment

For Eastwood, Two Mules for Sister Sara was more than just a difficult shoot—it was a turning point. Shortly after, he began to assert more creative control over his projects, directing his first film, Play Misty for Me (1971), and later delivering some of the most acclaimed works of his career: High Plains Drifter (1973), The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), and the Oscar-winning Unforgiven (1992).

These films allowed Eastwood to explore the themes he cared about—violence, redemption, and the myth of the American West—on his own terms. In contrast, Two Mules for Sister Sara remained an uncomfortable reminder of a time when he was not yet the master of his own fate.

Personal Life, Public Scrutiny

Eastwood’s personal life has been as complex as his professional one. He’s been married twice, to Maggie Johnson and later to Dina Ruiz, and has had several high-profile relationships, including with actress Sondra Locke and flight attendant Jacelyn Reeves. He is the father of at least eight children, many of whom have pursued their own careers in entertainment.

Despite his status as a Hollywood icon, Eastwood has always guarded his privacy fiercely. His political views—often described as libertarian—have made headlines, and his brief tenure as mayor of Carmel-by-the-Sea, California, only added to his mystique.

But through it all, Eastwood has remained, above all, a filmmaker. His directing style—favoring natural light, minimal takes, and efficient schedules—has become legendary. Films like Million Dollar Baby (2004), Gran Torino (2008), and American Sniper (2014) have shown that, even in his later years, he remains a vital force in American cinema.

The Episode That Haunts Him

Today, Two Mules for Sister Sara is a curious footnote in Eastwood’s career—a film that fans and critics alike rarely discuss, and that the actor himself has chosen to forget. The reasons are rooted in creative conflict, personal dissatisfaction, and a longing for artistic integrity. For Eastwood, watching the film would mean revisiting a period of frustration, compromise, and disappointment.

In the grand tapestry of his career, it is a single, stubborn thread—a reminder that even legends have moments they’d rather not relive.

News

UNBELIEVABLE POWER — ELON MUSK’S 10-SECOND APOLOGY JUST ADDED $191 MILLION TO TESLA’S VALUE! BUT THE TRUTH BEHIND HIS WORDS IS SPARKING A FIRESTORM AND LEAVING MILLIONS SPEECHLESS | HO~

UNBELIEVABLE POWER — ELON MUSK’S 10-SECOND APOLOGY JUST ADDED $191 MILLION TO TESLA’S VALUE! BUT THE TRUTH BEHIND HIS WORDS…

Joy Behar tried to trap John Kennedy with a leaked email | HO~

Joy Behar tried to trap John Kennedy with a leaked email | HO~ Joy Behar, co-host of The View, leaned…

Joy Reid sees career ROCKET after her firing from MSNBC | HO~

Joy Reid sees career ROCKET after her firing from MSNBC | HO~ The polarizing pundit has amassed more than 168,000…

Just moments ago, Fifth Avenue felt like it stopped breathing. Jeanine Pirro, eyes blazing, turned to Robert De Niro and dropped a truth bomb so sharp it cut straight through the air | HO~

Just moments ago, Fifth Avenue felt like it stopped breathing. Jeanine Pirro, eyes blazing, turned to Robert De Niro and…

Blake Shelton stunned viewers on Good Morning America when he abruptly walked off the set after a tense, on-air clash with George Stephanopoulos | HO~

Blake Shelton stunned viewers on Good Morning America when he abruptly walked off the set after a tense, on-air clash…

Connie Francis Left Behind A Fortune So Big, It Makes Her Family Cry | HO!!

Connie Francis Left Behind A Fortune So Big, It Makes Her Family Cry | HO!! By the time reports of…

End of content

No more pages to load