Woman Born in 1843 Talks About the One Thing She Regrets Most – Enhanced Audio | HO

I think about it every day. Have for thirty years. Thirty years of wishing I could go back and change what I did, change what I didn’t do. But you can’t go back. That’s what they don’t tell you when you’re young. You can’t go back and fix your mistakes. You have to live with them.

I was born in 1843, November. Cold month. My mother said it snowed the day I was born, the kind of snow that makes the world look clean even when it isn’t. I was the first child, the oldest. Then came my sister Margaret, two years younger than me. After Margaret came three brothers—William, Henry, and John—five of us total.

But Margaret and I, we were close when we were young. Shared a room, shared clothes, shared secrets. You know how sisters are. Or maybe you don’t. Maybe you were an only child. But Margaret and I, we were everything to each other.

We grew up in Pennsylvania. My father had a mill, a grist mill down by the creek. People brought grain to be ground—wheat, corn, barley, whatever they had. Father charged by the bushel: five cents a bushel for wheat, three for corn. The mill ran from dawn to dusk. The sound of it, that grinding sound, constant. You could hear it throughout the house. Sometimes I still hear it in my dreams. Wheat becoming flour, corn becoming meal, that steady work turning hard kernels into something useful.

Father worked hard. We did well. Not rich, but comfortable, better than most families in the area. Two-story house, four bedrooms, a proper parlor. Good food on the table every day—meat twice a week. Good clothes that weren’t mended hand-me-downs. I never wanted for anything growing up. None of us did. Father made sure of it, and he made sure we understood what it cost him.

We were expected to be grateful and to show it by being good children—obedient, disciplined, quiet. Father was strict, very strict. He believed children should know their place, be seen and not heard, do as they were told without question or argument. We had rules for everything: when to wake up, when to eat, how to sit at the table, how to speak, what we could say and what we couldn’t. No running in the house. No loud voices. No playing on Sundays. Everything ordered. Everything had its place.

We learned to obey. Learned quickly. Father’s hand was heavy when rules were broken. Mother never interfered. Never said, “Go easy,” or, “They’re just children.” She stood behind Father’s decisions always. That was how things were done. The father was head of the household. His word was law. Everyone else obeyed. That was proper. That was right. That was how it should be.

Here’s the hinged sentence that started it all without me noticing: when you’re taught that being “good” means never disrupting peace, you learn to treat silence like virtue—even when it becomes cruelty.

Margaret and I were different from the beginning, and those differences grew sharper as we did. I was serious even as a child. Thoughtful, careful, responsible beyond my years. I did what I was supposed to do without being told. Kept my room clean. Made my bed every morning with the corners folded just so. Did chores without complaint. Practiced my letters until they were perfect. Never gave Father reason to be disappointed. Never gave Mother cause to scold. I took pride in being the good daughter, the reliable one. The one Father could point to and say, “See, that’s how children should be.”

I wanted his approval. Needed it. Worked for it every single day.

Margaret was different. Lighter somehow, as if rules didn’t weigh on her the way they weighed on me. She laughed more, sang while she worked, talked when she should have been quiet, forgot to make her bed some mornings, left her things scattered around our room, daydreamed when she should have been concentrating on lessons. Father would scold her. She’d apologize—“Yes, Father. I’m sorry, Father. I’ll do better”—and she meant it. She truly did. But then a week later she’d do the same thing again, forget chores, lose track of time, leave the butter churn half finished because she got distracted watching birds through the window.

It wasn’t deliberate. She wasn’t trying to be difficult. She just was. That was Margaret: always somewhere else in her head, always seeing something beautiful the rest of us missed.

It irritated me. Her carelessness, her inability to simply do what she was supposed to do. It seemed so easy to me. You get up, you do your chores, you follow the rules, you do what’s expected. Simple.

But for Margaret, it wasn’t simple. And that irritated me more than anything because I couldn’t understand it. Why couldn’t she be more like me? Why did I have to cover for her mistakes? Why did I have to do her chores when she forgot? Why did I have to make excuses when Father asked why something wasn’t done?

It seemed profoundly unfair. I was doing everything right and she was getting by doing half of what she should, less than half sometimes, and nobody seemed to notice. Nobody seemed to care. Father would scold her when he caught her, but it never changed anything. Somehow she remained Father’s sweet Margaret even when she failed.

That made me angry. Made me resentful. Made me work even harder to be perfect, to be above reproach, to be the daughter who never failed, never disappointed, never required covering for.

As we got older, the differences grew more pronounced. I became more rigid, more proper, more concerned with doing everything exactly the right way—the way Mother and Father expected. I internalized their rules, made them my own, became stricter with myself than they ever were. I measured everything I did against what was proper, what was right, what was appropriate, and I always came up short in my own estimation. Could have done better. Should have been more careful. Should have thought ahead more. That constant self-judgment became who I was.

Margaret became more free. That’s the only word I have for it: free. As she grew into a young woman, she seemed to shed the weight that pressed down on the rest of us. She’d laugh at things that weren’t funny. Sometimes for no reason at all, just because she felt like laughing. She’d say things that weren’t proper—observations too honest, comments that made people uncomfortable. She’d question Father’s rules, not openly, not in a way that would bring real punishment, but in little rebellions.

When Father said girls shouldn’t ride a horse astride, only side-saddle, Margaret argued it was impractical. When Mother insisted we wear our hair a certain way, Margaret wore it differently the next day. Nothing major. Just small assertions that she was her own person. And somehow she got away with it. Father would shake his head and say, “That’s Margaret,” and let it go. If I had done those things, he would have been furious. But with Margaret, he was lenient, indulgent even.

That made me angry too. It made me feel like my effort to be perfect was pointless, that being responsible and proper didn’t count as much as being charming and free.

Here’s the hinged sentence that I wish someone had whispered to me when I was young: resentment is just love that got no place to go and turned sharp.

When I was twenty, I married George Bennett. He owned land near Father’s mill. Good land. He was steady, reliable, responsible like me. Father approved. Said George would provide well, that I’d have a good life. He was right. George provided. We had a good house, six children over the years. I kept it clean, cooked good meals, raised the children properly, did everything a wife should do. I was proud of my life, proud of my house, proud of my children, everything in its place, everything done right.

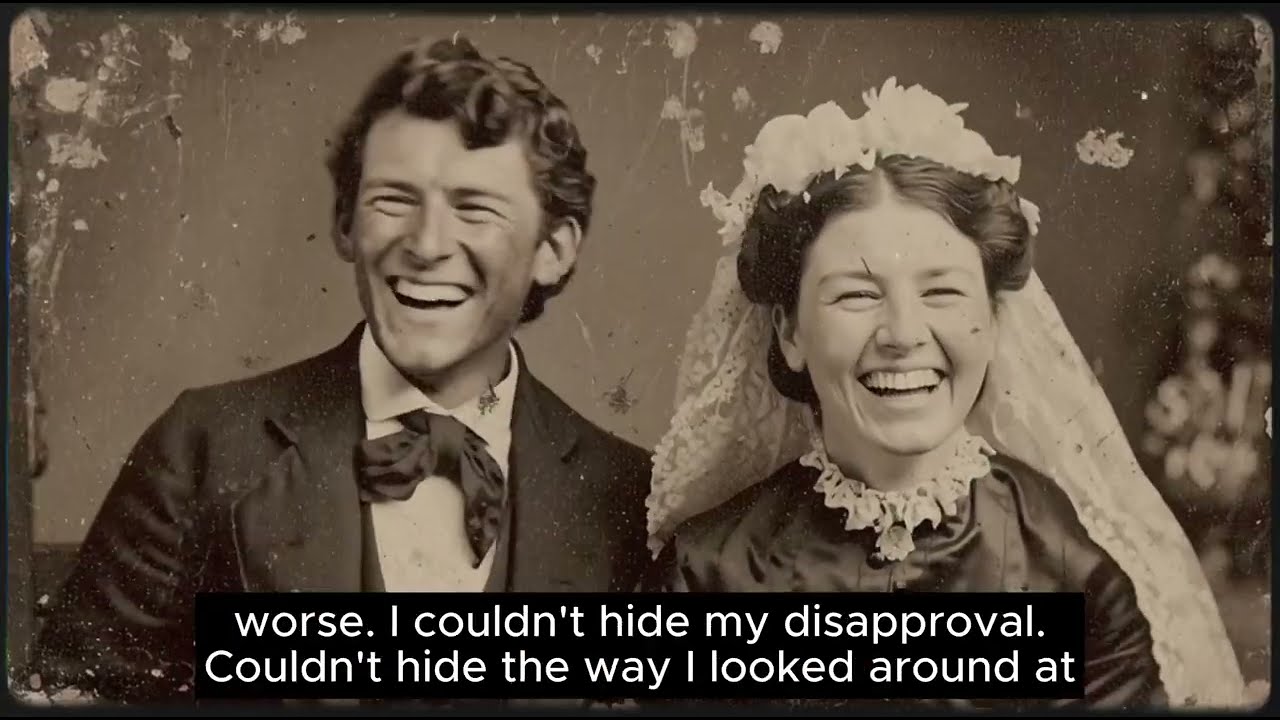

Margaret married two years after me. Daniel Foster. He was different from George. Not as steady. Not as reliable. Charming, everyone said. Handsome. Good talker. But he didn’t have much. Didn’t own land. Worked odd jobs. Sometimes worked at Father’s mill, sometimes for other people. Never stuck with anything long. Never seemed to save. Margaret didn’t seem to care. She loved him. You could see it in her face when she looked at him—how her whole face lit up. The way she laughed at his jokes, touched his arm when they talked.

I didn’t approve. I thought she should have chosen better, someone stable, someone who could provide properly. I told her so before the wedding. I told her she was making a mistake.

She smiled at me—Margaret’s infuriating smile—and said, “Maybe. But I’d rather be happy with Daniel than comfortable with someone I don’t love.”

That made me angry. It made me feel like she was saying I didn’t love George. That I’d chosen comfort over love. That wasn’t true. I did love George, just in a different way. A sensible way. A grown-up way.

After Margaret married, we saw less of each other. She lived in town. I lived on George’s farm, three miles apart—close, but not close enough for daily life to braid itself together. We saw each other at church, at family gatherings. It wasn’t the same. We were busy with our own lives, our own houses, our own husbands, our own children.

Margaret had three boys—wild boys who ran loud and got dirty. My children were better behaved, quieter, more proper. I made sure of that.

The trouble started small, so small I barely noticed at first. Little things that built up over the years like dust collected in corners.

Margaret would come to family dinners late. Not terribly late—fifteen minutes, twenty—but late. She’d arrive flustered, apologizing, laughing it off. Daniel lost track of time fixing something. One of the boys needed help. Someone’s shoe couldn’t be found. Always some reason they couldn’t arrive on time like everyone else.

I arrived on time. Always. Exactly. George and I and the children were there when Mother said to be there, not a minute late. It bothered me that Margaret couldn’t do the same. It felt like a lack of respect, a lack of consideration, a lack of basic courtesy. If Mother said dinner at five, you arrived at five. Not 5:15. Not 5:20. Five.

Then there was Margaret’s house. I visited once when the children were young. She invited me for tea, said she wanted to show me the house. It was small—two rooms downstairs, two upstairs—nothing fancy, but it could have been cozy. Instead, it was a mess. Toys everywhere. Dishes in the sink from breakfast, maybe from the night before. Laundry piled on a chair by the fire—clean, probably, but not folded, not put away, just heaped like someone had forgotten it existed. The floor needed sweeping. Crumbs under the table, mud tracked in from outside. The whole place felt cluttered, chaotic, like a house no one was managing.

Margaret didn’t seem bothered. Didn’t apologize. Just offered tea as if everything was fine, as if she couldn’t see what I was seeing. Or maybe she could see it and simply didn’t care, which felt worse.

I couldn’t hide my disapproval. I know I couldn’t. My eyes went to the corners, the pile of laundry, the dishwater. My face must have shown what I thought: How can you live like this? Don’t you have any pride? Any standards?

Margaret noticed. I saw something change in her face, something close off like a door shutting. Her smile became fixed—polite, not warm. She poured the tea with hands that shook slightly and changed the subject to the weather.

We drank in awkward silence. I left early, said I had things to do. She didn’t try to convince me to stay longer. She walked me to the door, said goodbye, and that was that.

I walked home angry. Angry at the mess. Angry that she didn’t care. Angry that she wasted my visit by not making things presentable. It never occurred to me that maybe she had tried. That maybe with three boys and a husband who drifted between jobs, keeping a perfect house wasn’t possible. That maybe she was doing the best she could and my judgment made her feel small.

I didn’t consider her perspective. I only saw disorder and called it failure.

I started making comments. Little ones—not mean, I told myself, just observations. Her house should be kept better. Her boys needed more discipline. Daniel should find better work. They should save money instead of spending it on nonsense.

Margaret would nod and say, “You’re probably right, Harriet.” But she didn’t change.

That frustrated me. If she knew I was right, why wouldn’t she fix it? Why wouldn’t she do things properly? Why wouldn’t she be more like me?

Here’s the hinged sentence that I didn’t understand until it was too late: when you confuse control with love, you start correcting the people you should be holding.

The breaking point came in 1876. I was thirty-three. Margaret was thirty-one. It was Mother’s birthday dinner. The whole family was there—Father and Mother, my brothers and their families, George and me with our children, Margaret and Daniel with their boys. The table was crowded, too many people for Mother’s dining room, but we made it work. We always did.

During dinner, Margaret mentioned Daniel had been offered a job. A real job. A good job. Managing a store in Ohio—steady pay, respectable work. They’d have to move, leave Pennsylvania, leave family. But it was an opportunity, a chance for Daniel to prove himself, a chance for them to do better.

Margaret seemed excited and nervous. She looked around the table, waiting for someone to say something.

I spoke first.

I shouldn’t have. I should have kept quiet. But I didn’t.

“Ohio,” I said. “That’s a terrible idea. Daniel will mess it up like he messes up everything else. You’ll be stuck out there with no family, no support, and no money when it all falls apart.”

The words came out harder than I meant them. Harsher. But I thought I was being honest. I thought I was being helpful—warning her, protecting her from making another mistake.

The table went silent. Forks stopped. Everyone stared.

Margaret’s face went white, then red. Her eyes filled. Daniel put his hand on her arm as if to steady her. He started to say something, but Margaret stood up, shoved her chair back so hard it nearly fell.

“We’re leaving,” she said, voice shaking. “Boys. Get your coats.”

Daniel tried to calm her. Told her to sit, to finish dinner. She wouldn’t. She grabbed her shawl, gathered the boys, and left without saying goodbye to anyone. Just walked out.

Daniel followed after apologizing to Mother, apologizing for Margaret, like she was the one who’d done something wrong.

The door closed.

Everyone looked at me—Father, Mother, my brothers, their wives, George. Even the children stopped and stared.

“What?” I said. “Someone needed to tell her the truth.”

Father cleared his throat and went back to eating. Conversation restarted, awkward and forced, but the dinner was ruined. We left early. George drove the wagon home in silence, reins tight in his hands.

When we got home, George finally spoke. “You were too hard on her, Harriet,” he said. “She’s your sister. You should have been kinder.”

I didn’t answer. I didn’t want to admit he might be right.

Margaret and Daniel moved to Ohio three weeks later. They didn’t tell me. Didn’t say goodbye. I found out from Mother. Mother said Margaret was hurt, said she cried when she told her what I’d said, said she didn’t want to see me or talk to me and needed time.

I was angry. I was hurt. I’d been honest. I’d been trying to help. And this was how she thanked me—cutting me out, leaving without a word.

Fine, I thought. If she wanted to be that way, fine. I had my own life. I didn’t need her. I was the older sister, the responsible one. If she wanted to make mistakes, that was her choice. I’d done my duty. I’d warned her. It wasn’t my fault she didn’t listen.

Here’s the hinged sentence that turned a fight into a lifetime: the night I chose to be “right” in front of everyone, I quietly chose to lose my sister in private.

Years passed. Mother gave me updates. Margaret and Daniel were doing well in Ohio. The store was successful. Daniel was good at it. The boys were growing up. They bought a house. Everything Margaret hoped for was coming true.

I told myself I was happy for her.

But there was something bitter underneath. Something like resentment, or shame, or the sick feeling of realizing I might have been wrong. I thought about writing to her. I thought about apologizing. Several times, I sat down with paper and pen and started letters.

Dear Margaret, I’m sorry for what I said. I was wrong.

But I never finished them. Never sent them. Pride got in the way. I couldn’t admit I’d been wrong. Couldn’t admit I’d hurt her. Couldn’t make myself vulnerable like that. So I waited. Waited for her to reach out first, waited for her to forgive me, waited for her to make the first move.

She never did. And I never did.

And the years kept passing—ten, then twenty.

Mother died in 1892. Margaret came back for the funeral. I saw her at church. She looked older—gray in her hair, lines around her eyes—but still Margaret, still that light in her face, like she carried spring inside her even when the day was cold. Daniel was with her, still handsome, still charming. The boys were men now.

Margaret saw me across the church. Our eyes met. I thought maybe this would be it. Maybe she’d come over. Maybe we’d talk. Maybe we’d fix it.

But she looked away. Sat on the other side with Daniel and the boys. After the service, she left quickly. Didn’t stay for the gathering. Didn’t say goodbye. Just left.

Father died two years later. Same thing. Margaret came back. We were in the same room, the same building, but we didn’t speak. Didn’t even look at each other. Like we were strangers. Like we’d never been sisters at all, never shared a room, never shared secrets, never laughed under quilts at night.

My brothers noticed. Henry asked why Margaret and I weren’t speaking. I told him it was complicated, old business, told him to let it go. He did. Everyone did. Nobody wanted to get involved. Nobody wanted to force reconciliation. So the silence continued, fed by everyone’s discomfort and my own stubborn pride.

In 1900, William told me Margaret was sick. Something with her lungs—pneumonia or consumption, he wasn’t sure. She wrote to him asking him to come visit. Wanted to see family. Wanted to see Pennsylvania again.

William planned to go to Ohio. He asked if I wanted to come.

I said no.

“I’m too busy,” I told him. “I have my own family to take care of. I can’t just leave for a trip to Ohio.”

William looked at me for a long moment, eyes tired, voice low. “She’s your sister, Harriet,” he said. “She might be dying.”

I told him not to be dramatic. Told him Margaret was always dramatic. Told him she’d be fine.

He left without me.

Here’s the hinged sentence that has followed me like a shadow: I didn’t miss her because I couldn’t go—I missed her because I refused.

A month later, William came back. He came to my house on a Tuesday morning. George answered the door, let him in, called for me. I was in the kitchen making bread, kneading dough, hands covered in flour. I wiped them on my apron and went to the parlor.

William was standing by the window. Not sitting. Just standing, staring out like he couldn’t face what he had to say.

I knew from his face something was wrong. Something terrible.

“She’s gone,” he said. He didn’t turn. Just kept looking out. “She’s gone.”

Margaret died two days before William got there. Two days. Forty-eight hours. If he’d left a day earlier, if the train had been faster, if anything had been different, he might have made it. Might have held her hand. Might have told her she was loved.

But he didn’t make it. He got there too late.

The funeral had already happened the day before he arrived. Daniel and the boys buried her in the cemetery in town—small service, just them, a few neighbors, a few church friends. Nobody from Pennsylvania. Nobody from her family except William arriving after the ground had settled and the flowers were already wilting at the edges.

William told me he went to the grave and brought white roses—Margaret’s favorite. He stood there alone, with his coat collar up, wind cutting through him, and he said her name like it might bring her back if he said it hard enough.

I don’t remember much about the rest of that day. The details blur. I remember William stayed a few hours. Told me Daniel looked broken. Absolutely broken. The boys too—devastated. Margaret had been the light in that house, the warmth and laughter, and now she was gone and they didn’t know how to manage without her.

William said Daniel asked about me. Asked if I might come visit. William had to tell him probably not. Had to explain without explaining that Margaret and I hadn’t spoken in years.

Daniel nodded like he already knew, like Margaret had carried that hurt all those years and it had become part of her marriage the way weather becomes part of a roof.

William asked me why. Why we stopped speaking.

I couldn’t answer. Couldn’t get the words out. I just shook my head and started crying. He didn’t push. He sat with me, then he left, saying he was sorry. Sorry for my loss, like Margaret had been mine to lose.

But she hadn’t been mine for twenty-four years. I’d given up that right.

And I grieved anyway. Grieved like I hadn’t grieved for anyone, not even for Mother or Father. George tried to comfort me, put his arm around me. I pushed him away. I didn’t want comfort. I didn’t deserve it.

This was my fault. My doing. I destroyed my relationship with my sister. I let pride and stubbornness keep me from making things right.

Now she was gone, and I would never be able to fix it. Never take back what I said. Never apologize. Never tell her I loved her. Never tell her she was right about Daniel, right about Ohio, right about everything, and I was wrong—wrong to judge her, wrong to criticize her, wrong to value being right over being kind.

I went to my room that night and sat on the bed I’d slept in for forty years—George’s bed, our bed—and the full weight of it hit me. Not just that Margaret was dead, but what that meant.

She was gone. My sister. My only sister. The girl I’d shared a room with, shared secrets with, grown up with.

And I had never apologized.

Twenty-four years. Twenty-four years of silence and foolish certainty. Twenty-four years I could have written a letter, could have visited, could have swallowed pride and reached out. Twenty-four years of chances—wasted because I was too stubborn, too sure she should apologize first, too convinced I was the injured party.

And now there were no more chances. No more opportunities. No more moments. Just the finality of death and the knowledge I had failed her, failed myself, failed us both.

Here’s the hinged sentence that I can’t escape: the cruelest thing about pride is that it feels like strength right up until the moment it becomes a coffin lid.

That was twenty-three years ago. I’m eighty now. Eighty. And I think about Margaret every single day. Every day. I think about what I said to her. How I hurt her. How I was too proud to apologize. How I wasted those twenty-four years.

People ask about her sometimes—grandchildren, great-grandchildren. They ask if I had siblings. I tell them yes. A sister named Margaret. They ask what she was like. I tell them she was beautiful, funny, kind, that she loved her family, that she was happy. All of that is true.

But I don’t tell them the rest. I don’t tell them I hurt her. I don’t tell them I was cruel. I don’t tell them I never apologized. I don’t tell them I let pride destroy the most important relationship I had besides George.

I keep that to myself. Carry it like a stone in my chest. Heavy. Always there. Never getting lighter.

That’s why, when my hands began to shake and my memory started slipping in little ways—misplacing a pin, forgetting a name I should have remembered—I bought that small voice recorder. It wasn’t for drama. It wasn’t for stories. It was for reminders. Take your medicine. Call the church. Don’t forget the bread in the oven.

But it became something else.

At night, when the house is quiet and even the old floorboards settle, I take it out and hold it like a confession I can’t deliver to the person it belongs to. I press the button and speak the apology I never gave.

“Margaret,” I say, voice thin. “I’m sorry. I was wrong. I was cruel. I should have been kinder. I should have supported you. I should have been a better sister.”

I imagine her smiling. Imagine her saying, “It’s all right, Harriet. I forgive you.” I imagine us hugging, being sisters again.

But it’s just imagination. Wishful thinking. She isn’t here to forgive me. She never will be. I had my chance and I wasted it.

If I could go back, I’d change everything. I’d bite my tongue at Mother’s birthday dinner. I’d let Margaret share her news and I’d be happy for her. I’d tell her Ohio sounded like a wonderful opportunity. I’d tell her I was proud of her, proud of Daniel for getting that job. I’d hug her and wish her well and tell her to write.

And when she left for Ohio, I’d write to her every week, every month. I’d tell her about my life and ask about hers. I’d visit. I’d make the trip to Ohio. I’d see her house, meet her friends, see how happy she was, and I’d tell her I was sorry for doubting her, for thinking my way was the only right way.

But I can’t go back. Can’t change it. Can’t fix it.

That’s what I’ve learned. You can’t undo the past. Can’t unsay words. Can’t undo hurt. You have to live with your mistakes. Live with your regrets. Live with the knowledge you failed someone you loved. That’s the punishment—not other people’s anger, not the family’s gossip, not the minister’s disapproval. Just your own knowledge of what you did and didn’t do.

I tried to be different with my children, with my grandchildren. I tried to be kinder, less rigid, less sure my way was the only way.

When my daughter Anna wanted to marry a man I didn’t approve of, I kept my mouth shut. I smiled. I welcomed him into the family. They’ve been married twenty years now. They’re happy. He’s been a good husband, a good father. I was wrong about him, just like I was wrong about Daniel. But this time I didn’t let pride ruin a relationship. This time I learned from my mistake, even if it was too late for Margaret.

When my son Robert told me he was moving to California, I didn’t tell him it was a terrible idea. I hugged him. Told him I’d miss him. Told him to write. Told him I loved him. And he did. Every month. He’s been in California fifteen years now. He’s doing well. He comes back when he can. We have a good relationship because I didn’t do to him what I did to Margaret.

Too late for her. Not too late for him.

That’s the lesson, I suppose. The thing I learned too late: love is more important than being right. Relationships are more important than pride. Family is more important than your ego.

You can be right about everything and still lose everything that matters. You can be proper and responsible and do everything correctly and still destroy the people you love. Being right doesn’t matter if it costs you the people who matter most.

I wish I’d learned that earlier. Wish I’d learned it before it cost me my sister. But I didn’t. And now I have to live with that.

If you have someone you need to apologize to, do it now. Don’t wait. Don’t think you’ll have more time. Don’t let pride stop you. Don’t let stubbornness keep you from saying the words.

Say them.

Say you’re sorry. Say you were wrong. Say you love them. Say whatever needs to be said. Because one day it will be too late. One day they’ll be gone and you’ll be left like me with regrets, with guilt, with that crushing knowledge that you had your chance and you wasted it.

I see Margaret sometimes in my dreams. She’s young again. We’re young again, back in the room we shared as children. She’s laughing—light and free. I try to tell her I’m sorry. Try to tell her I was wrong.

But I can’t speak. The words won’t come. Then I wake up and she’s gone again, and I’m old again, and it’s too late again. Always too late.

I’ll die with this regret. I know I will. It’ll be the last thing I think about—not the children or the grandchildren or my long marriage to George or the things I did right. I’ll think about Margaret. About what I said to her. About what I didn’t say. About all the years we lost. About how I let pride destroy the bond between us.

That’s the one thing I regret most.

Not that I spoke too harshly at dinner—though I did. The worst part, the part I can’t forgive myself for, is that I never apologized. I had twenty-four years. Twenty-four years to write a letter, to visit, to say I was sorry, to tell her I loved her, to fix what I broke, and I didn’t.

And now, that little recorder sits in my drawer beside a few hairpins and a folded handkerchief. I took it out for reminders once. Then I used it as proof to myself that I still had a voice. Now it’s something else entirely—a symbol of what I finally learned, too late: words can ruin a life, but they can also save one, if you say them in time.

News

56 YR Woman Died Left A LETTER For Her Husband ”They Are Not Your Kids” What He Did Next Was Heartbr | HO!!

56 YR Woman Died Left A LETTER For Her Husband ”They Are Not Your Kids” What He Did Next Was…

After Spending All Their Savings On An OF Lady, He Went Ahead To 𝐁𝐫𝐮𝐭𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐒𝐭𝐚𝐛 His Wife, But She | HO!!

After Spending All Their Savings On An OF Lady, He Went Ahead To 𝐁𝐫𝐮𝐭𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐒𝐭𝐚𝐛 His Wife, But She |…

Everyone Accused Her of K!lling 5 of Her Husbands, Until One Mistake Led To The Shocking Truth | HO!!

Everyone Accused Her of K!lling 5 of Her Husbands, Until One Mistake Led To The Shocking Truth | HO!! They…

Dad And Daughter Died in A Cruise Ship Accident – 5 Years Later the Mother Walked into A Club & Sees | HO!!

Dad And Daughter Died in A Cruise Ship Accident – 5 Years Later the Mother Walked into A Club &…

2 Years After She Forgave Him for Cheating, He Gave Her 𝐀𝐈𝐃𝐒, Leading to Her Painful 𝐃𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐡 – He Was.. | HO!!

2 Years After She Forgave Him for Cheating, He Gave Her 𝐀𝐈𝐃𝐒, Leading to Her Painful 𝐃𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐡 – He Was…..

She Nursed Him For 5 Yrs Back To Life From A VEGETABLE STATE, He Paid Her Back By K!lling Her. Why? | HO!!

She Nursed Him For 5 Yrs Back To Life From A VEGETABLE STATE, He Paid Her Back By K!lling Her….

End of content

No more pages to load