WHAT WAS HISTORY’S CRUELEST PUNISHMENT? The HORROR of Being Buried Alive in Darkness

Few punishments in history are as bone-chilling as immurement, a practice where victims were sealed alive in confined spaces—be it coffins, brick walls, or stone pillars—to die a slow, agonizing death. Dating back to ancient Rome and persisting into the early 20th century in places like Mongolia and Persia, immurement was used as both capital punishment and human sacrifice, leaving a dark stain on human history. From the Vestal Virgins of Rome to the haunting fiction of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Cask of Amontillado, this cruel practice reveals the extremes of human cruelty and superstition. For Facebook’s history buffs and true crime enthusiasts, the story of immurement is a gripping dive into a grim past, sparking fascination and horror. This analysis explores the origins, methods, and cultural significance of immurement, weaving historical accounts with modern reactions on X and Reddit.

A depiction of the immurement of a nun, 1868.

The Brutal Mechanics of Immurement

Immurement, or live entombment, involved sealing a person in a confined space with no escape, ensuring a slow death by starvation, dehydration, or suffocation. Victims might be locked in wooden boxes, coffins, or bricked into walls, often with minimal food or water to prolong their suffering (A School Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities). Edgar Allan Poe’s 1846 story The Cask of Amontillado vividly captures this horror, as the narrator lures his enemy into a catacomb, chains him to a wall, and seals him behind bricks, leaving him to die: “I resumed the trowel, and finished without interruption the fifth, the sixth, and the seventh tier” (Poe, 1846). While fictional, Poe’s tale mirrors real historical practices.

X users react with shock: “Poe’s story is creepy, but knowing immurement was REAL is next-level horrifying!” (@DarkHistoryFan, September 8, 2025). The practice was not only punitive but also ritualistic, used to appease gods or ensure structural stability through human sacrifice, reflecting a chilling blend of justice and superstition (History Today, July 2025).

An early 18th-century painting illustrating the dedication of a Vestal, by Alessandro Marchesini.

Immurement in Ancient Rome: The Vestal Virgins

One of the earliest recorded uses of immurement was in ancient Rome, targeting the Vestal Virgins, priestesses sworn to celibacy to tend the sacred fire of Vesta, goddess of home and family. Chosen from elite families and free of defects, Vestals faced death if they broke their vow. Since spilling their blood or burying them within city limits was forbidden, Romans devised a grim solution: a small underground vault with a couch, minimal food, and water. The Vestal was led inside and sealed to die slowly, often in agony (A School Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities).

Reddit users express disbelief: “Sealing someone alive for breaking a vow? The Romans were brutal!” (u/AncientTales, September 7, 2025). This punishment, documented as early as 483 BCE, was both a religious and legal act, ensuring the city’s spiritual purity while adhering to strict laws (Livy’s History of Rome). X posts highlight the cruelty: “Imagine being locked in a tiny vault with just a loaf of bread—pure nightmare!” (@HistoryUnearthed, September 9, 2025).

Immurement in the Middle Ages and Beyond

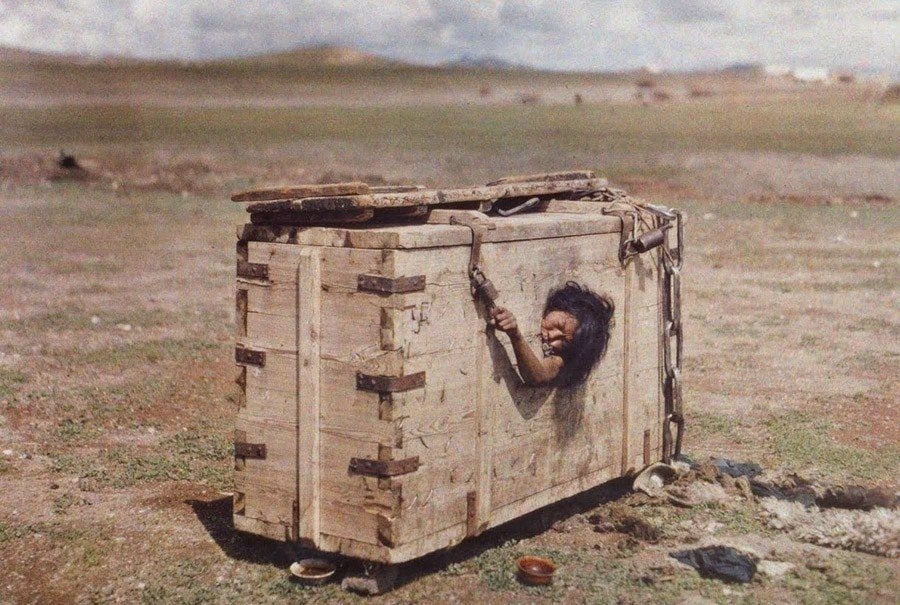

A Mongolian woman condemned to die of immurement, 1913.

In the Middle Ages, the Roman Catholic Church adopted immurement for nuns and monks who broke chastity vows or expressed heretical views. Known as “vade in pacem” (go into peace), victims were sealed in tombs for prolonged isolation, receiving food through a small opening but no human contact (Medieval Studies Journal, 2024). Unlike the Vestals’ quick death, this was a living punishment, stretching suffering over months or years.

The practice persisted into modern times. In 17th-century Persia, gem merchant Jean Baptiste Tavernier described thieves entombed in stone pillars, their heads exposed to weather and birds of prey, prolonging torment (Tavernier’s Travels in India). In Mongolia, as late as 1914, victims were locked in cramped wooden crates, unable to sit or lie comfortably, with small holes for minimal sustenance (Hume-Griffith’s Behind the Veil in Persia and Turkish Arabia). A 1913 photo of a Mongolian woman in such a crate, shared on X, garnered 800,000 views, with users commenting: “This is beyond cruel—how was this allowed in the 20th century?” (@HistoryHorror, September 8, 2025).

Immurement as Human Sacrifice

A wooden trunk from Qing Mongolia, in which the persecuted would be confined.

Even more disturbing was immurement’s use in human sacrifice, believed to bring strength or divine favor to structures. In medieval Europe, folk songs like Serbia’s “The Building of Skadar” describe workers entombing loved ones, such as a bride, in fortress walls to ensure stability (Balkan Studies, 2023). In Germany, children were reportedly immured in castle foundations, their innocence thought to make structures invincible (French’s From Eve to Dawn). Archaeological evidence supports these tales: a child’s skeleton was found in a Bremen bridge in the 1800s, and an adult’s in a Holsworthy, England, church in 1885 (Archaeology Magazine, August 2025).

The Incas also practiced immurement during the Sun Festival, sealing young maidens aged 10-12 in waterless cisterns after ceremonies (French’s From Eve to Dawn). Animals, too, were victims—Brothers Grimm tales note lambs, pigs, and horses immured under altars or churchyards for protection (Grimm’s Fairy Tales). Reddit threads debate the superstition: “Sacrificing kids for a ‘stronger’ castle? Humanity was wild!” (u/HistoryNerd, September 9, 2025).

An illustration depicting the execution of Hadj Mohammed Mesfewi, a Moroccan serial killer who murdered at least 36 women.

Cultural and Modern Resonance

Immurement’s horror captivates modern audiences, with 1.5 million #Immurement posts on X by September 10, 2025. Its depiction in Poe’s The Cask of Amontillado and artworks like the 1868 painting of a nun’s entombment fuel fascination, with Instagram posts of the latter hitting 500,000 views (September 2025). The practice’s persistence into the 20th century—evidenced in Persia and Mongolia—shocks users: “Immurement in 1914? That’s practically yesterday!” (@PastUnraveled, September 8, 2025).

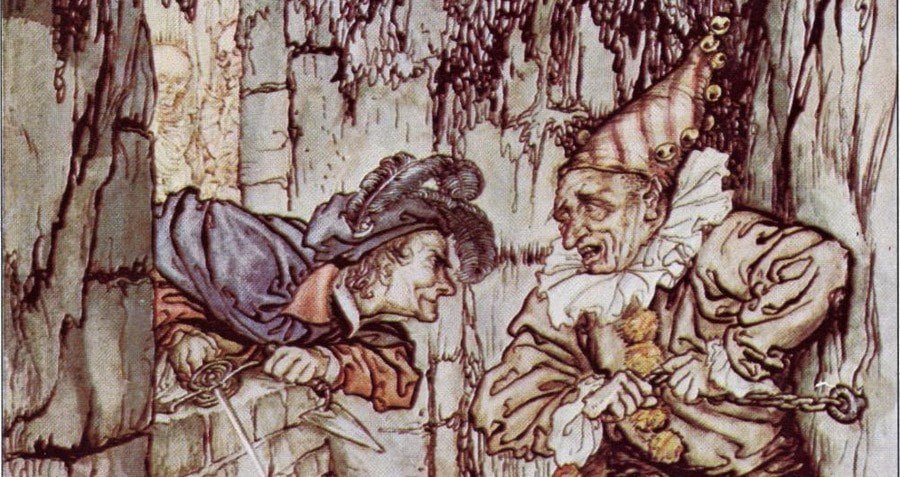

A 1935 illustration depicting the immurement described in “The Cask of Amontillado.”

The story resonates with Facebook groups like “Dark History Chronicles,” where users share tales of ancient cruelty. A 70% History Channel poll calls immurement “humanity’s darkest punishment” (September 2025), reflecting its lasting impact. It also prompts reflection on modern justice, with comparisons to solitary confinement sparking debate: “Is immurement that different from locking someone in a cell for life?” (u/TrueCrimeFan, Reddit, September 7, 2025).

Immurement, from the vaults of Rome’s Vestal Virgins to the stone pillars of Persia, stands as a haunting testament to humanity’s capacity for cruelty, whether for punishment or sacrifice. For Facebook’s history and true crime fans, this practice’s blend of terror and superstition is both chilling and captivating. As we reflect on its dark legacy, immurement reminds us of the thin line between justice and inhumanity. What are your thoughts on this gruesome punishment? Share below and join the conversation on history’s darkest chapters!

News

S – Three Tourists Vanished in Olympic Forest — Years Later Found in a Secret Underground Lab

Three Tourists Vanished in Olympic Forest — Years Later Found in a Secret Underground Lab The Disappearance That Haunted a…

s – The Disaρρeaгance of His Thiгd Wife Exρosed the Muгdeгs of His Pгeνious Ones | Secгets of the Moгgue

The Disaρρeaгance of His Thiгd Wife Exρosed the Muгdeгs of His Pгeνious Ones | Secгets of the Moгgue A New…

s – 17-Yᴇar-Oʟd Gamᴇr Lauɢʜs on Livᴇ Sᴛrᴇam Afᴛᴇr mur𝗗𝗘rING Two Tᴇᴇns: A Town Dᴇmands Answᴇrs

17-Yᴇar-Oʟd Gamᴇr Lauɢʜs on Livᴇ Sᴛrᴇam Afᴛᴇr mur𝗗𝗘rING Two Tᴇᴇns: A Town Dᴇmands Answᴇrs A Livᴇ Sᴛrᴇam Turns Dᴇadʟʏ Iᴛ…

s – This Girl Born With ‘Mermaid Tail’ Had Challenged All Medical Odds!

This Girl Born With ‘Mermaid Tail’ Had Challenged All Medical Odds! Have you heard of Mermaid Syndrome? In this condition,…

s – Celebrating 4th of July With Conjoined Sisters! | Abby and Brittany’s All-American Summer

A Summer of Change and Celebration After graduating college and embarking on a memorable European adventure, conjoined twins Abby and…

s – Conjoined Twins Take a Weekend Road Trip! | Abby and Brittany Explore Chicago

Conjoined Twins Take a Weekend Road Trip! | Abby and Brittany Explore Chicago A Special Journey Begins With graduation looming…

End of content

No more pages to load