Experts Discover Old 1886 Photo of Gang Leader In A Bar… They Zoom in and Immediately Turn Pale | HO!!!!

PRESCOTT, ARIZONA — What began as a routine archival scan at the Prescott Territorial Heritage Museum quickly spiraled into one of the most astonishing historical revelations in recent memory. A single, dust-covered photograph—unearthed from a forgotten trunk—has not only rewritten the legend of the Old West, but exposed a century-old conspiracy that left historians and federal crime archivists stunned.

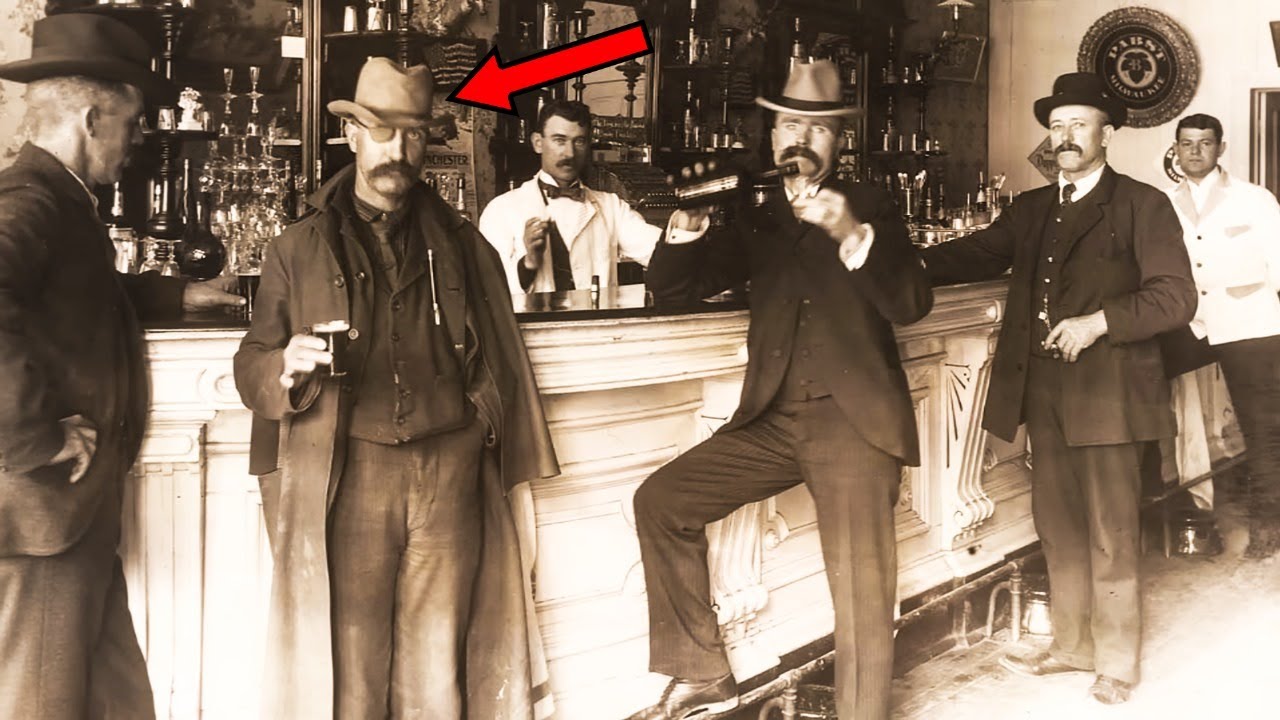

The photo, dated March 1886, shows a group of men gathered inside the Crystal Gulch Saloon, laughing over drinks and poker chips. At first glance, it’s a classic scene of frontier camaraderie. But when researchers zoomed in, they turned pale. The image would soon ignite a firestorm among experts, unraveling the myth of outlaw justice and revealing a secret handshake between criminals and the very lawmen sworn to hunt them.

A Routine Day, a Shocking Find

It was supposed to be a typical day for Dr. Emily Hartwell, a senior historian at the University of Arizona, and her research assistant Jonah Reyes. Volunteering at the museum, they were tasked with cataloging items from the estate of Leland McGra, a recently deceased cattle rancher. Among the expected odds and ends—rusted knives, moldy playing cards, and yellowed ledgers—they found a wooden frame wrapped in oil cloth. Inside, a remarkably preserved sepia-toned photograph.

The caption etched at the bottom read: “Crystal Gulch Saloon, March 1886.”

Hartwell and Reyes began the digitization process, scanning the image for details. The saloon was lively, even in stillness: lanterns hung from the rafters, wanted posters and liquor ads adorned the walls. Men in wide-brimmed hats and gun belts lounged around a table strewn with shot glasses and cigars. But one figure, standing dead center, drew their focus.

He wore a dark vest, high-collared shirt, and a cowboy hat pulled low over one side of his face. An eye patch slashed diagonally across his brow—an unmistakable mark of legend. In his hand, a raised shot glass, as if toasting history itself.

Hartwell stared, her pulse quickening. “That can’t be,” she whispered.

Jonah leaned in. “No way.”

The man bore a striking resemblance to One-Eyed Tom, notorious leader of the Hollow Raven Gang—a name that haunted Western folklore. According to territorial records and Pinkerton files, One-Eyed Tom was the mastermind behind the infamous 1885 Gila Ridge train robbery, where $70,000 in military payroll vanished without a trace. Eyewitnesses described him as cold, clever, and unkillable. No photograph had ever surfaced—until now.

But the shock didn’t end there.

Lawmen and Outlaws—Side by Side

In the back left of the photograph, two men stood shoulder-to-shoulder with the supposed gang leader. Both wore long black coats and U.S. Marshal badges pinned to their vests.

After cross-referencing their faces with law enforcement rosters, Hartwell and Reyes confirmed the impossible: Marshals William J. Cartwright and Emory Vance. Both men were celebrated in historical accounts for dying in pursuit of One-Eyed Tom and his gang, allegedly ambushed in the Arizona canyons in spring 1886.

Yet here they were—alive, smiling, drinks in hand, standing beside the man they were said to be hunting.

Had history been manipulated? Was the chase a lie? The implications were staggering.

Hartwell and Reyes quietly uploaded the image to the museum’s database, forwarding it to a select group of federal crime archivists and 19th-century law enforcement specialists. Within days, a name resurfaced in official channels that hadn’t been spoken in more than a century: One-Eyed Tom.

The Ripple Effect

The photo’s journey through confidential federal channels triggered a ripple across historians, archivists, and law enforcement analysts. Requests poured in for access to sealed Pinkerton reports and marshal dispatch logs, mothballed for decades under obscure jurisdictional clauses.

Inside the declassified archives were scattered descriptions of Tom Whitaker—aka One-Eyed Tom—suspected born in Missouri, 1849. Orphaned young, he fought as a courier in the Civil War before vanishing into outlaw circles. His Hollow Raven Gang became infamous for bold crimes, culminating in the Gila Ridge train heist. Six guards dead, $70,000 missing. The official story claimed Cartwright and Vance died chasing the gang into the desert, their bodies never found.

But the Crystal Gulch photo shattered that narrative. Here was One-Eyed Tom, alive and drinking with the lawmen who supposedly died trying to capture him. The expressions were casual, almost celebratory. It wasn’t a confrontation—it was a gathering.

Questions multiplied. Were Cartwright and Vance undercover agents who turned? Did they fake their own deaths and join the gang? Or was the entire story a staged pursuit, masking a deeper conspiracy?

The Paper Trail

As historians dug deeper, contradictions mounted. Official testimonies were signed under pressure. Dispatch logs missed dates. None of the marshals’ bodies were ever positively identified.

The National Archives declassified a cache of Pinkerton reports, telegraph correspondences, and payment slips marked with names of lawmen reported dead in confrontations with the Hollow Raven Gang—including Cartwright and Vance.

A deeper thread emerged: evidence that several frontier marshals, isolated and facing unpaid wages, secretly allied themselves with outlaw crews, exchanging protection for a cut of the spoils.

The $70,000 from the Gila Ridge heist was never recovered. The final report claimed the gang fled south and perished. But no bodies, no loot. With the photo showing them relaxed and unafraid mere weeks later, the story unraveled.

Some historians now believe the saloon meeting was a coordinated rendezvous—a final handshake before the gang vanished, protected by the very lawmen sworn to stop them.

A Map in the Shadows

The frontier, it seemed, had written its own history. But the photo held more secrets.

Graduate student Lillian Mendoza, working in digital archiving, reprocessed the image for exhibition. During a late-night enhancement session, she zoomed in on the bar counter behind one man’s elbow. Faint carvings, ignored as wear, formed a primitive map when colors were inverted and contrast adjusted.

The etching depicted a mountain range, winding river, and a boxed X in the foothills. With help from a geospatial historian, the map was matched to the Tumacacori Highlands near the Mexican border. The alignment of peaks, especially one known locally as Eliso—the bone—was too perfect to dismiss. Beside the X, crude letters read: “Raven end.”

Within hours, the museum board was briefed. Dr. Hartwell interpreted the map as a coded farewell—a message left by the gang for posterity. The theory was simple: the gang never fled south. They buried the money, staged their disappearance, and vanished under government noses.

The Expedition

Planning the search required secrecy. The implications—finding stolen government funds or proof of law enforcement corruption—were explosive.

Under the guise of a university-led archaeological expedition, Hartwell, a trusted team, and two federal agents ventured into the Tumacacori foothills. Guided by the etched map and topographical overlays, they narrowed the search to a collapsed mining shaft marked on 1880s land surveys as claim 27A.

After days of clearing brush and rubble, they uncovered rotted timber beams—remnants of a mine. Thirty feet in, in a small chamber reinforced by stone, they found a rusted iron crate sealed with a railway lock. Inside were stacks of decomposing government bonds, stamped “Department of the Treasury, 1885,” a sack of silver coins fused with time, and a revolver engraved “TM.”

Nearby, in a niche dug into the stone wall, lay skeletal remains—likely male, partially mummified by dry desert air. Wrapped in oiled canvas, tucked between rocks, was a leather-bound journal.

Scrawled inside the cover: “Property of Thomas M. Whitaker. If you find this, the story was never finished.”

They had found One-Eyed Tom.

The Journal’s Confession

Carefully restored and scanned, Tom’s journal was more than a record of crimes—it was a confession, a memoir, and an exposé of the rot beneath the badge of frontier justice.

Tom chronicled the gang’s operations with military precision, revealing names of marshals respected in modern institutions. “We waited outside El Paso, just like Marshall D told us. The train was heavy, loaded with northern bonds, Washington’s orders. He said we’d get a 30-minute window. He delivered.”

The infamous 1885 train robbery, long thought to be a violent heist, was orchestrated with lawmen’s complicity. The journal described a quiet network of alliances—marshals turned a blind eye for a share of the loot or political leverage.

One entry, dated days before the saloon photo, was damning: “They’ll write songs about how he vanished, but they won’t know the truth. It was never about glory. It was about bleeding the system dry from the inside. That photo, that’s our last laugh. A room full of ghosts celebrating what the world couldn’t see.”

The photo, long misattributed and mislabeled, was a trophy—a farewell toast that challenged over a century of mythmaking.

Most chillingly, Tom wrote of a coordinated escape. The gang had safe passage through corrupt officials along the border, with caches of gold and documents planted to mislead investigators. Their disappearance was planned, vanishing not in a blaze of glory, but under the protection of the lawmen meant to stop them.

Rewriting History

The discovery has sent shockwaves through historical and law enforcement circles. What was believed to be a tale of brave pursuit and justice served was, in fact, a cover story—fabricated to protect reputations and conceal alliances.

The Crystal Gulch Saloon photo, once a dusty relic, is now a symbol of the West’s deepest secrets. It stands as a reminder that history is written not just by victors, but by those clever enough to hide the truth.

News

Steve Harvey stopped Family Feud and said ”HOLD ON” — nobody expected what happened NEXT | HO!!!!

Steve Harvey stopped Family Feud and said ”HOLD ON” — nobody expected what happened NEXT | HO!!!! It was a…

23 YRS After His Wife Vanished, A Plumber Came to Fix a Blocked Pipe, but Instead Saw Something Else | HO!!!!

23 YRS After His Wife Vanished, A Plumber Came to Fix a Blocked Pipe, but Instead Saw Something Else |…

Black Girl Stops Mom’s Wedding, Reveals Fiancé Evil Plan – 4 Women He Already K!lled – She Calls 911 | HO!!!!

Black Girl Stops Mom’s Wedding, Reveals Fiancé Evil Plan – 4 Women He Already K!lled – She Calls 911 |…

Husband Talks to His Wife Like She’s WORTHLESS on Stage — Steve Harvey’s Reaction Went Viral | HO!!!!

Husband Talks to His Wife Like She’s WORTHLESS on Stage — Steve Harvey’s Reaction Went Viral | HO!!!! The first…

2 HRS After He Traveled To Visit Her, He Found Out She Is 57 YR Old, She Lied – WHY? It Led To…. | HO

2 HRS After He Traveled To Visit Her, He Found Out She Is 57 YR Old, She Lied – WHY?…

Her Baby Daddy Broke Up With Her After 14 Years & Got Married To The New Girl At His Job | HO

Her Baby Daddy Broke Up With Her After 14 Years & Got Married To The New Girl At His Job…

End of content

No more pages to load