Experts Uncover Civil War Era Photo of Black Family – They Zoom In and Get the Shock Of Their Lives! | HO!!

It began, as so many great discoveries do, with a mystery. Two days after a plain, unmarked envelope arrived at the Eastwood Institute of American History in Charleston, South Carolina, the staff were still puzzling over its contents—a single, pristine photograph that seemed to defy everything historians knew about the Civil War era.

By the time they finished examining it, what they found would challenge long-held assumptions about race, family, and survival in one of America’s darkest periods.

A Discovery That Defied Logic

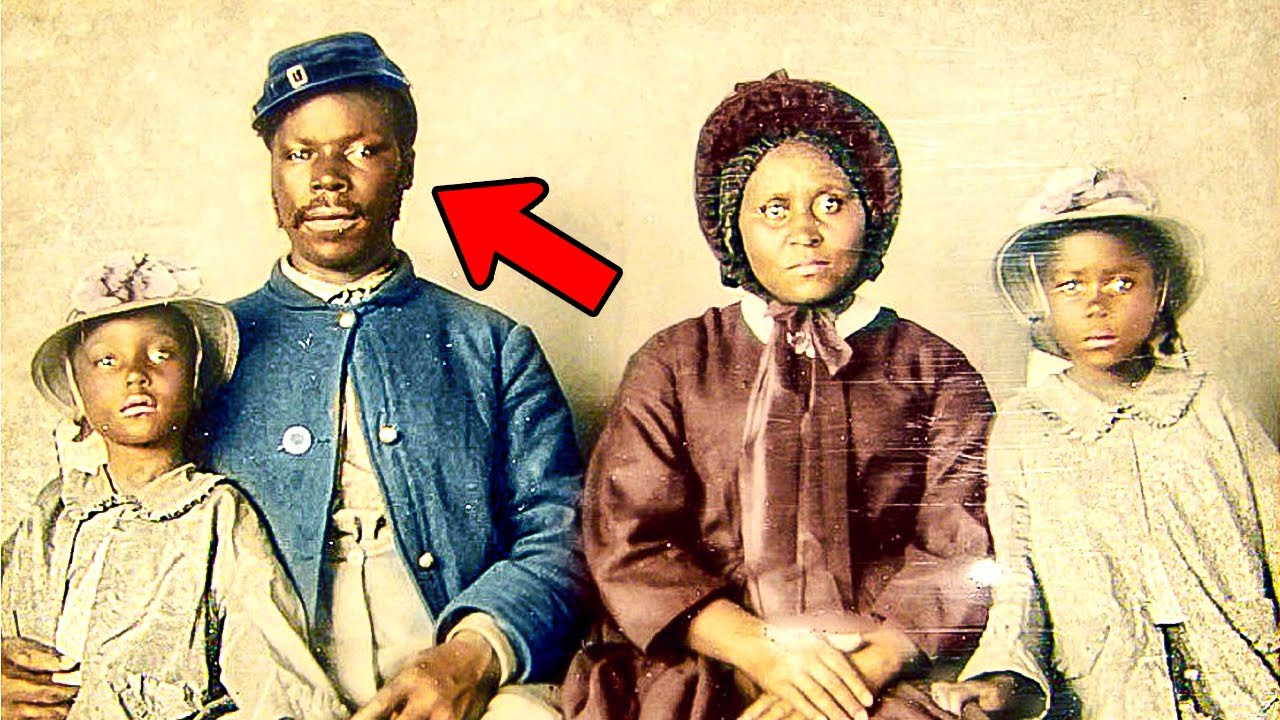

The envelope was labeled simply “for review.” Inside was a sepia-toned photograph, perfectly preserved, showing a Black family of four posed in a formal arrangement. The father wore a blue Union Army uniform, his hand resting solemnly on his lap. The mother, in a maroon bonnet and matching dress, sat beside him, hands folded.

Their daughters, perhaps seven and ten, flanked them in identical pale gray dresses and wide-brimmed hats adorned with pressed flowers. The composition was deliberate, symmetrical, and—most strikingly—professional.

Mason Cole, a Civil War historian with decades of experience, stared at the photo under glass, troubled. “There were no photographers working in this region during the war,” he muttered, brow furrowed. Leila Banks, a young digital restoration intern, agreed. “This looks staged—like a studio portrait. But if it was taken during the war, how did they get a shot like this?”

The preservation was “unnatural,” Mason said. The photo was scanned into the institute’s system and projected onto a large screen. Mason zoomed in on the soldier’s uniform. “It’s the First South Carolina Volunteers—the first Black regiment organized before the Emancipation Proclamation.” But something was off. “The shoulder epaulets look newer than they should. And I’ve seen every regimental photo. He’s not in any of them.”

A Trail of Clues

Ruth Henley, a senior historian, joined the investigation. She pointed out the painted curtain backdrop—a style used only by a handful of Union mobile photography wagons, rarely seen in the South. “We still have no clue where this was taken,” Leila said. “If anything, it feels like Georgia, but who would take this kind of photo in Georgia during the war?”

Ruth promised to dig through war records and soldier registries. By the next day, she had found a single, cryptic notation in a century-old ledger from an antique shop in Albany, Georgia: “Photograph soldier and Negro family 1865. Retrieved from Hargrove estate.”

The Hargroves, Mason explained, had owned one of the largest plantations in Georgia before the war. The estate was ransacked during Sherman’s march, and rumors persisted that Union forces had occupied it before it was abandoned.

With help from a local librarian, the team tracked down Edward Hargrove, an 81-year-old descendant living in Atlanta. “I don’t know much about that time,” Edward said, thumbing through a faded photo album. “But my grandfather used to say his father remembered a soldier passing through near the end of the war. He took nothing but a Bible and a photograph.” When Mason showed him the photo, Edward’s eyes widened. “That’s it. That’s the man from the family story.”

Anachronisms and Answers

Back at the institute, Ruth had spent the day examining the uniform’s stitching and the girls’ dresses. “This photo makes no sense,” she said. “The stitching on the girls’ sleeves is machine-perfect. That technology wasn’t available until 1871. But the photo’s paper, chemicals, and toning all match the mid-1860s. It’s not a fake.”

So how could a photograph from 1865 display sewing that shouldn’t exist for another six years? The next day, Mason and Leila visited the partially restored Hargrove house. In a crumbling root cellar, Leila found rotted photo paper scraps and a rusted lens cap engraved “Anthony and Scoville, NY”—a known Union supplier of portable cameras. Behind a wall panel, they discovered a tarnished metal box with water-stained letters inside.

One letter, dated February 22, 1865, was from a Union field nurse named Sarah Delaney. She described a “colored volunteer” arriving with his wife and two daughters, seeking someone to take their photograph. “He said he wouldn’t let the war end without proving they survived it,” she wrote. Delaney also praised the wife’s sewing skills, noting she “sews like her hands were built to handle the tiniest needles.” She had learned by braiding her daughters’ hair—a skill passed down by women on the plantation.

The answer was clear: the anachronistic stitching wasn’t from a machine, but from a mother’s extraordinary skill, born out of love and necessity.

A Family’s Hidden Story

Back at the institute, the team examined a high-resolution scan of the photograph. Leila noticed the father’s steady gaze, the mother’s faint smile, and the daughters’ gentle lean. Then Ruth entered with another photo, found in an obscure New Orleans archive and cataloged under the wrong year. “Same girls, women now, but same hats,” Ruth said. The image was dated 1878—thirteen years later. “So, they didn’t just survive. They thrived,” Mason said.

But where did they go? Mason replayed Edward Hargrove’s words: “He took nothing but a Bible and a photograph.” The next morning, Ruth called with a breakthrough. She’d identified the pendant partially hidden under the mother’s sleeve—a silver locket with the initials “AC,” matching a family heirloom from the Hargrove estate. “That’s Adeline Catherine Hargrove,” Mason realized. “Are you saying the woman in the photo was Edward’s great-aunt, the illegitimate daughter of the plantation owner, who married a Union soldier?” Ruth nodded. “Probably in secret, maybe right after the soldiers stormed the plantation.”

The story came into focus: a Black Union soldier, possibly once enslaved on the very estate, returning to claim his love—a forbidden romance, a daring escape. Two daughters, a mother’s skill, and a family determined to be remembered.

Piecing Together the Past

Mason contacted the New York Civil War Museum to check soldier records. After hours of digging, a researcher named Paula called back. “There’s one soldier who fits everything: Corporal Elijah Turner, First South Carolina Volunteers. Escaped a Georgia plantation in 1863, fought through Virginia, discharged in 1865. No death record, no grave—just disappeared.”

Leila zoomed in on the pendant in the photo. Etched on it, barely visible, were the words: “Eat together always. Elijah, Adeline, Turner.” “They weren’t just hiding,” Leila whispered. “They were protecting something.” Ruth nodded. “Their story.”

Why had the photo been hidden behind a wall and left in an unmarked envelope 160 years later? Someone—perhaps Elijah himself—wanted the world to know they lived, loved, and survived, even if their love was forbidden by the world around them.

The Final Clue

Before the story broke, Mason took one last look at the digital scan. Using infrared technology, he noticed a faint double exposure beneath the father’s seat. Enhancing the image, he revealed four names scratched into the wood: Adeline, Elijah, Rebecca, Mary. “Rebecca and Mary were the daughters,” Mason said. “They match baptismal records from 1866 and 1869 in a Union Army chapel.”

A Quiet Revolution in History

The story first appeared in niche history forums, then in major news outlets. But the Eastwood Institute made a deliberate choice: no sensational headlines, no dramatized theories. Instead, they mounted an exhibition titled “One Family, 1865.” The original photograph, digitally restored and encased in bulletproof glass, was displayed beneath soft lighting. A simple plaque read: “A family united. Their names are known to few. Their love seen by all.”

On opening day, hundreds gathered—students, veterans, families, strangers. Among them was a young girl named Amari, no older than ten, who stood in front of the photo with her mother. “So, they were real?” she asked. Her mother smiled. “Yes, they were.”

A Legacy Uncovered

The photograph didn’t just shock the experts—it changed them. It reminded the world that behind history’s harshest moments were families who dared to love, even when the world gave them no permission. Now, over a century later, that love sits quietly behind glass, untouched, unforgotten, and finally seen.

Can a single forgotten photograph rewrite history? Perhaps not alone. But it can remind us that the past is never truly buried—and that every family, no matter how hidden, deserves to be seen.

What would you have done if you were the one who uncovered that hidden detail? Would you protect their secret, or share their story with the world?

News

Elvis Sang to His Daughter After Divorce — His Voice Cracked — She Asked ”Why Are You Crying?” | HO!!

Elvis Sang to His Daughter After Divorce — His Voice Cracked — She Asked ”Why Are You Crying?” | HO!!…

Chicago Mafia Boss Vanished in 1963 — 60 Years Later, His Cadillac Is Found Buried Under a Speakeasy | HO!!

Chicago Mafia Boss Vanished in 1963 — 60 Years Later, His Cadillac Is Found Buried Under a Speakeasy | HO!!…

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon – Found Hiding 4 Months Later Found Inside TREE’S Hollow, Whispering | HO!!

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon – Found Hiding 4 Months Later Found Inside TREE’S Hollow, Whispering | HO!! Here was…

Nat Turner The Most Feared Slave in Virginia Who 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 55 in 48 Hours and Terrified the South | HO!!

Nat Turner The Most Feared Slave in Virginia Who 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 55 in 48 Hours and Terrified the South | HO!!…

He Told Ozzy Osbourne ‘You Can’t Afford This Vintage Guitar’—Then Ozzy Flipped It Over and Froze Him | HO!!

He Told Ozzy Osbourne ‘You Can’t Afford This Vintage Guitar’—Then Ozzy Flipped It Over and Froze Him | HO!! Ozzy…

He 𝐒𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐞𝐝 Her $25,000 To Use to Marry a Younger Woman – But She Paid Him Back on His Wedding Day| HO

He 𝐒𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐞𝐝 Her $25,000 To Use to Marry a Younger Woman – But She Paid Him Back on His Wedding…

End of content

No more pages to load