George Burns Left His Fortune To ONE Person, You Will Never Guess Who | HO!!

In March of 1996, George made a decision nobody saw coming. He wrote the kids completely out of his will. Every dollar went somewhere else entirely. His family was left with nothing but questions, and friends started saying what friends say when they’re trying to protect the dead and still tell the truth: there were things George never told anyone, there were reasons that didn’t make it into the obituaries, there were doors in that Beverly Hills house that stayed closed even when the living room was full.

“Hasn’t your doctor said to you, ‘Now, George, you got—’” someone teased him once, trying to pull him back into the old rhythm.

“My doctor is dead,” George snapped, and the room laughed because it was funny, and because it was easier than hearing the fear underneath.

He left behind a story people wanted to turn into a punchline: the beloved comic who abandoned his children. But George didn’t do punchlines. He did setups that took a lifetime.

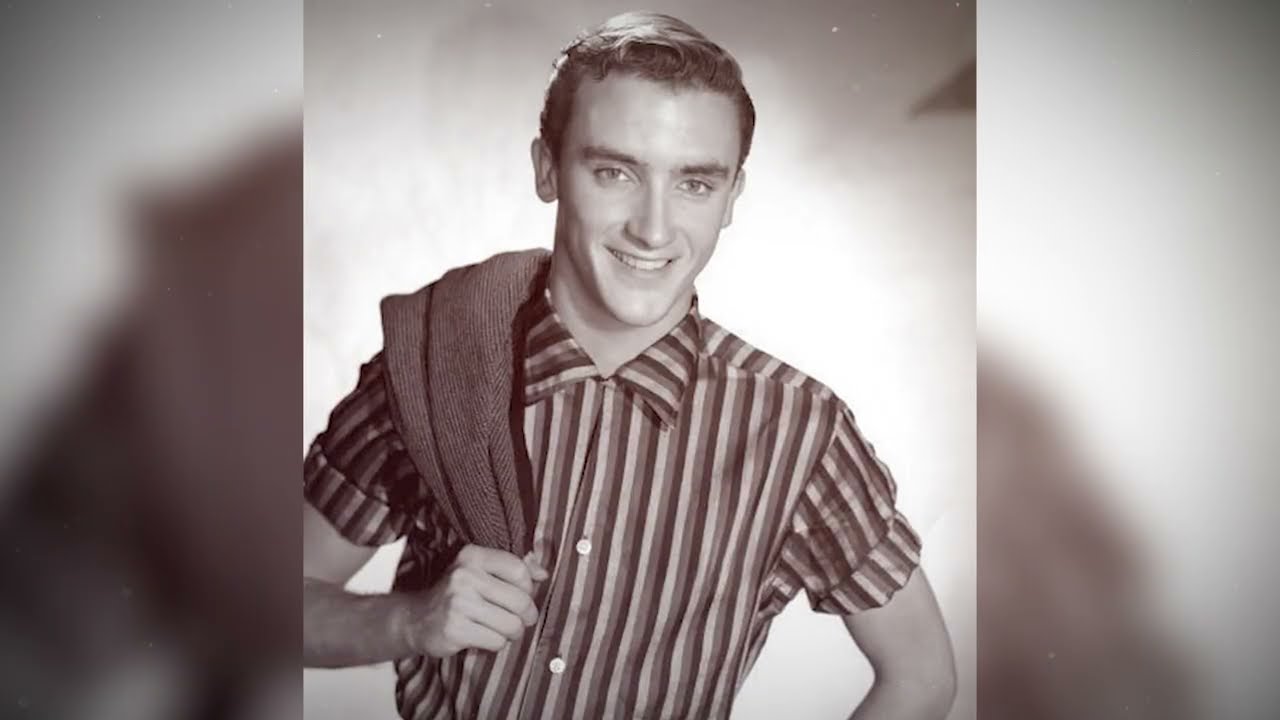

He came into the world on January 20, 1896, in a small apartment at 95 Pitt Street on New York’s Lower East Side, where life moved fast and loud and nobody had space for silence. His name then was Nathan Birnbaum, and the building held immigrant families like a clenched fist.

His parents, Dora and Louis, had fled hardship in Eastern Europe and carried old habits into a cramped new world. They had twelve children; he was the ninth. Three tiny rooms held all of them. Warmth came from bodies more than blankets. Louis worked as a caner and barely brought in enough to keep the family breathing. Dora scrubbed clothes for neighbors to stretch a dollar until it cried uncle.

Most kids wore hand-me-downs and shared beds. Many nights, dinner was nothing more than potatoes and onions. Even bread felt like a gift you weren’t sure you deserved. Yet George remembered the laughter—the Yiddish jokes, the rhythm of arguments and affection bouncing off thin walls. Humor wasn’t entertainment; it was insulation.

Everything changed in 1904. He was eight when his father died suddenly at forty-seven. No savings. No backup. Fifth grade was the end of school for him, because the rent didn’t care about report cards. He stood on street corners shining shoes for a nickel a shine.

Cold, dirty, long hours, and he kept going anyway. Sometimes he earned extra by singing with a children’s quartet called the Imperial Five. One night, their promoter ran off with the money. George had nowhere to go and slept in alleyways, learning what real hunger and real fear felt like.

He carried those nights like secret training. They taught him toughness and street sense he’d use for the rest of his life, the kind you can’t buy and can’t fake. His family called him Natty. Other kids called him “Shoes” Birnbaum because of his shine box. He rolled cigars. He sold newspapers.

He slipped into burlesque theaters to watch comedians shape laughter from nothing and thought, I want that kind of power. During his early teens, he made a reckless bet and tried swimming across the East River. The current pulled him under and he almost didn’t come back up.

That moment scared him—and lit him up.

Soon he tried on stage names like borrowed coats. “George Burns” came from his brother Izzy, from “George Birnbaum,” and from the Burns Brothers Coal Company—because once, trying to keep his family warm, he’d stolen coal from them. Later he tried names like Willie Delight and Captain Betts just to fool booking agents and stay employed.

At fourteen, he felt the urge to run, so he did. In 1910 he left home and joined the Mickey Rooney Stock Company, hoping to make it as a singer. His first paid performance happened in a Midwestern theater. He froze, forgot every lyric, and the crowd booed until pennies hit the stage like hard rain. He was fired on the spot.

“I couldn’t do it in the room,” he’d say later, smiling as if he was remembering a joke instead of humiliation. “But on the stage, I can because the audience is so wonderful.”

He wandered through the Midwest singing on ferryboats, in brothels, on street corners—anywhere that might offer a little money. Some days he barely ate. Some nights he barely slept. He felt alive anyway. By 1913, at seventeen, he formed a singing trio called the Burning Three with sisters Beatrice and Irene. They toured rough vaudeville houses filled with tough crowds. Irene eloped with a sailor, leaving George and Beatrice stranded with no cash. George begged for train fare and crawled back to New York with empty pockets and a bruised ego.

“You can quit,” someone might have told him. “Normal people quit.”

George wasn’t normal, and quitting never crossed his mind.

The years taught him how to improvise when shady theater owners refused to pay, how to keep his face steady when failure slapped him in public, how to turn panic into timing. When World War I arrived, he tried to join the Navy, but they rejected him for being too short—5’7″ when they wanted taller. Instead of giving up, he found another route.

He disguised himself as a woman named Barbara and slipped into groups of entertainers traveling on troop ships. It was risky; one mistake could have meant police, questions, consequences he didn’t want to name. He sang for homesick soldiers while praying he wouldn’t be discovered. Later, he laughed about it, but at the time it was pure survival, another reinvention that kept him working.

In 1916, he thought he’d caught a break when he teamed with dancer Elsie Loraine. They built a ballroom act and played the East Coast. Elsie left him for a wealthier man and George was stranded again. Broke and tired, he took a job as a soda jerk on Coney Island’s boardwalk. He served ice cream and practiced jokes on customers.

One guy frowned. “You calling that funny?”

George leaned in like he was sharing a secret. “Not yet. But give me a minute.”

Some laughed. Some walked away. All of them taught him timing. He later joked that the job did more for his career than any producer ever did. By 1920 he was performing alone, using “George Burns” full-time, working speakeasies during Prohibition where police raids could happen at any moment.

One night he had to hide in a coal bin to avoid getting caught. When he climbed out, he was covered in black soot and humiliated—yet strangely energized, as if the universe had confirmed he belonged in places with danger and an audience.

He realized he needed a partner, someone who could balance him on stage, someone whose rhythm would make his restraint look smarter. That partner appeared in 1923. He met Gracie Allen in Chicago at a booking office. He was auditioning with dancer Maggie Healey, but fired her in frustration when she forgot her lines. Later he bumped into Gracie, a twenty-seven-year-old Irish American performer whose family act had fallen apart.

“You looking for work?” George asked, casual like it didn’t matter.

Gracie blinked. “I’m looking for the right kind of work. Is this the right kind?”

He invited her to try his act. They rehearsed. George planned to be the funny man while she played straight. The first time they stepped in front of a crowd, everything flipped. People laughed at Gracie’s innocent confusion. Her voice, her timing, the way she could derail a simple sentence into a perfectly timed surprise pulled every eye toward her. George saw it instantly.

After the show, he didn’t sulk. He adjusted.

“Listen,” he told her, the way a smart boxer talks between rounds, “you be the character. I’ll watch you. I’ll make it look like I’m in control.”

Gracie nodded as if he’d just explained math. “That sounds fair. Do I have to be in control too?”

Their first show together at the Hill Street Theater in New York proved the magic was real. Laughter rolled in waves. An early routine called “60/40” taught them what worked and what didn’t. George admitted there was a feeling between Gracie and the audience he could never compete with—so he didn’t compete. He framed her like a jewel.

By 1924 they joined the Pantages circuit and built hits like their “Dizzy” and “Lamb Chops” routines. They made $50 a week and even bought their first car. Life started to open. Then fear showed up in a familiar suit. Another performer was courting Gracie. On Christmas Eve of 1925, George cornered the moment.

“You have to choose,” he told her, too blunt to be romantic. “Marry me or walk away.”

It was bold and messy. Gracie agreed. They married January 7, 1926, in Cleveland. Small ceremony. Huge impact. Weeks later they signed a six-year contract with RKO requiring neither perform alone. It locked them together in a partnership that would last decades, a legal promise that matched their personal one.

Then shadows arrived. Gracie began fainting during rehearsals. Doctors traced it to a heart condition that would follow her for life. George looked at this woman who could light up a theater with a single confused question and realized the body carrying that light was fragile.

“Are you okay?” he’d ask, trying to sound like a husband and not a manager.

Gracie would smile like she’d forgotten she owned pain. “I’m fine. I just have to sit down so I can stand up later.”

In 1927 they headlined the Palace Theater in New York, the summit of vaudeville. They earned $1,500 a week. From the outside, it looked like overnight success. Behind it were years of hunger, role-switching, and George’s willingness to let Gracie be the spark. Critics compared them to the Marx Brothers. The crowds loved Gracie’s strange logic, how it made no sense and landed every time.

Two years later, in 1929, they crossed the Atlantic for a BBC radio tour that lasted fifteen weeks. British customs seized George’s cigars, and he’d been smoking since he was ten. He stood there empty-handed, irritable, and turned withdrawal into material.

“You know what they took?” he told the audience later, deadpan. “My happiness. It was in a box.”

The British loved it. Their routines traveled across a continent that didn’t know them and still welcomed them. By 1931 they were in the Ziegfeld Follies, sharing the stage with stars like Eddie Cantor. Travel exhausted Gracie. She hated flying, so trains became endless, clacking corridors of fatigue. During one show she twisted her ankle mid-performance. The pain hit sharp. George picked her up, carried her onstage, and she kept acting as if nothing happened. The audience never knew. Backstage, he whispered, “You can stop.”

Gracie looked at him like he’d suggested they cancel gravity. “If we stop, they’ll worry. I don’t want them to worry.”

Around that same time, George did something few entertainers dared. While others spent money on clothes and fancy hotel rooms, he used their earnings to quietly buy foreclosed real estate after the 1929 crash. He bought properties for pennies while the country panicked. When the Depression hit and theaters shut down, those investments kept them afloat. Performers who’d been kings on Friday were broke by Monday. George had seen the wave and built a raft.

Their film debut came in 1930 with Paramount shorts like “Lamb Chops.” Even that moment came with chaos. At one screening the reel jammed and the projector exploded, burning George’s eyebrows and filling the room with smoke. People panicked. George stood there blinking through soot and made a joke as if it was part of the show. Executives watched him turn fear into laughter in seconds.

That’s when they understood: he wasn’t lucky—he was trained.

Their radio breakthrough arrived February 15, 1932, when The George Burns and Gracie Allen Show began on NBC. Fifteen minutes an episode, built around Gracie’s misunderstandings that somehow solved everything. By the mid-1930s, nearly 40 million people tuned in each week. The style was loose, often improvised, full of surprises. Ratings jumped from 19.3 to 31.3 within a year, more than a 60% rise. Listeners heard real laughter, real confusion, real sparks between them.

In 1933, Gracie ran a fake presidential campaign as part of a long routine called the “Surprise Party.” She toured 39 states and printed ballots. Some voters even wrote her name in during the real 1940 election, confusing local officials until they realized it was a gag. She promised to tax only the right kind of clouds and hand out cabinet jobs to friends with nice outfits. The mascot was a kangaroo. The slogan was “It’s in the bag.” The campaign boosted their ratings by nearly 40% and made people ask, uncomfortably, how easily entertainment could blend with politics.

Behind the scenes, their partnership kept surprising people. George wrote nearly every script but publicly insisted Gracie was the creative force. In an era when men usually took all the credit, he pushed it away from himself like it was hot. In a 1935 episode, Gracie joked she’d forgotten she was married to George. Fans thought it was real. Thousands of letters arrived accusing George of mistreating her. He went on live radio to clear it up.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” he said, calm as a priest, “we’re fine. She remembers me. Sometimes.”

Instead of hurting them, the confusion boosted ratings by 20%. People loved that their fiction felt real.

They moved to CBS in 1934 for $10,000 a week—an almost unbelievable number when most Americans made under $2,000 in a year. They blended real events into the show. When Gracie needed an emergency appendectomy in 1937, they wrote it into the storyline and even brought real doctors onto the broadcast. The mix of truth and comedy made audiences feel close, like they were part of the family.

In 1938 they bought a mansion in Beverly Hills. It should’ve been peace. One night, George left a lit cigar on a table. It rolled, burned through fabric, sparked a fire that spread faster than anyone expected. They barely saved the house. Newspapers had a field day. Instead of hiding it, they turned the scare into an episode called “The House That Burns Built.” Gracie blamed herself in the script and spun disaster into jokes. America fell in love with them all over again, because they could laugh at their own mistakes.

Hollywood became a chapter, too. Their national profile exploded after a big broadcast in 1932 featuring “Love in Bloom.” But studio censors kept pushing back. Executives thought Gracie’s dizzy logic sounded too suggestive and demanded rewrites. George would sneak original lines back in as ad-libs during filming, a playful rebellion that trained future comics how to fight rules without looking like they were fighting.

In 1933, during International House, a thin wire on Gracie’s chandelier stunt snapped and dropped her about ten feet. George happened to be beneath her and caught her, cracking two ribs. The set froze. Gracie looked down at him like she’d misplaced something. “Did I do that?”

George grunted, smiling through pain because the crew was watching. “No. Gravity did. You’re just cooperating.”

They kept going, laughing like the fall was planned. The moment ended up in the film, turning near tragedy into comedy legend. In 1937, working with Fred Astaire on A Damsel in Distress, Gracie panicked in an important scene, forgot steps, and blurted she was lost in London. Astaire didn’t miss a beat; he danced around her confusion and turned it into a spontaneous routine. He later called it pure magic.

During World War II, they performed for troops in 1941. Gracie got swept into a strange little scandal when silk stockings were scarce and she tried to smuggle a few pairs as gifts. Authorities treated it as contraband; she almost faced formal trouble until George pulled every string he had. Troops loved her more afterward. It revealed a side of Gracie the public didn’t always see: sweet, yes, but bold.

By 1945 they were at the top. Their film Two Girls and a Sailor brought in more than $4 million. But Gracie’s health declined. Migraines hit so hard she had to step away for six months. During her break, George started drafting his autobiography, wanting to preserve their story, especially the small moments only they knew. That draft would later become Gracie: A Love Story, and fans would feel the sincerity in it like a hand on the shoulder.

On October 12, 1950, CBS aired the first episode of The George Burns and Gracie Allen Show. It went live with a studio audience, risky at a time when television still leaned on radio habits. Then George did something new: he stepped out of scenes and talked directly to viewers. People felt pulled in, as if he were sitting beside them in the living room, elbow on the armrest, sharing the joke before it happened. The show ran 291 episodes until 1958 and brought them nearly $200,000 per season at its peak. They played versions of themselves in a simple home setting, letting America feel like it was peeking into their real life.

Episode 47 in November 1951 became one of those early-TV stories people retold because it proved anything could happen live. The setup was sweet: a surprise birthday party for George tied to Gracie’s old campaign bit. The surprise came from a prop cake that exploded too early. Frosting shot everywhere. The cast froze, then burst into real laughter. Producers let it air. People at home heard the studio’s shock and loved it.

But the laughter hid a private wound. In the early 1950s, George admitted he’d once had a one-night mistake while on tour. The guilt crushed him. He tried to make amends the way a man who knows prices tries to buy forgiveness: a $10,000 diamond ring and a $750 silver centerpiece. Gracie stayed quiet. She didn’t confront him. For decades, the public saw perfection. The truth slipped out later in his writing, and even then Gracie’s humor softened it. She once told Mary Livingstone, Jack Benny’s wife, that she wished George would stray again because she could use another centerpiece.

“I didn’t mean—” George would start, the way men do when they want to rewind time.

Gracie would tilt her head, gentle and maddening. “It’s okay. I like nice things.”

Love, in their house, was complicated and practiced. Forgiveness wasn’t a speech. It was a decision you made and then made again.

As the decade moved on, Gracie lost strength. Heart problems she’d carried since childhood became impossible to ignore. By 1957 she was too sick to keep up with filming. George kept it private. “She’s on vacation,” he told people, and the lie was an act of devotion. She pushed through angina, migraines, even performed after breaking her nose, but she couldn’t outrun her own body. She retired in 1958. On August 27, 1964, she died at Cedars of Lebanon Hospital in Los Angeles, taken by a heart attack at sixty-nine.

In 1956, while the show still ran, Jack Benny guest-starred. Fans loved seeing two giants together. Behind the scenes, George tripped over a cable and fractured his hip at sixty. He refused to stop working and filmed the rest of the season sitting down.

“I’m fine,” he told the crew, jaw clenched. “If the audience can sit through commercials, I can sit through my own show.”

The day Gracie died broke him. At her funeral, he nearly collapsed. He later said he’d cried only twice in his life: once for his mother, once for Gracie. For two years afterward, he kept an empty chair on stage during live shows. He would turn toward it and deliver lines to her as if she were just offstage. People cried with him. That chair became a symbol of a love that kept performing even after its partner was gone.

Without Gracie’s spark, his next attempt felt hollow. In 1965 he tried a new series, Wendy and Me, playing a landlord who spied on his tenants. It lasted one season. At sixty-nine, he wondered if his career had ended. He went back to nightclubs, rebuilt from scratch, and learned what it meant to stand alone after a lifetime as a duo.

By 1967 he hit a breaking point. He drank heavily, smoked nonstop. During a Las Vegas residency he collapsed on stage from exhaustion. Doctors told him he might not survive the year if he didn’t stop. He quit everything overnight—no alcohol, no cigarettes, no easy crutch. He said later that choice saved his life and bought him decades.

“You’re really quitting?” a friend asked, skeptical.

George’s eyes narrowed like he was timing a punchline. “I’m not quitting. I’m changing the ending.”

In 1968 he published a memoir, I Love Her, That’s Why, selling more than 100,000 copies. It mixed honesty with humor—details like Gracie forgetting where she parked her car—and it funded his first solo tour. He’d always been the observer beside her brilliance. Now he had to be his own center.

In 1975, he took a role that shocked Hollywood: Al Lewis in The Sunshine Boys with Walter Matthau. The film came out in December and earned instant praise. At the 48th Academy Awards on March 29, 1976, George won Best Supporting Actor at age eighty, beating younger stars including Richard Dreyfuss from Jaws. Hollywood gasped. The old vaudevillian had become a late-life legend.

The next year he starred in Oh, God! opposite John Denver. It earned more than $51 million and turned him into a new kind of icon: wisecracking, gentle, slightly mischievous. He even added a clause in his contract allowing cigars on set. He’d been smoking since he was fourteen and often went through ten to fifteen cigars a day.

A producer raised an eyebrow. “Do you really need it?”

George slid a cigar into his holder with the same stubborn grace he’d had at one hundred. “Need? No. But it helps the truth come out.”

In November 1983, at eighty-seven, he signed a five-year contract with Caesars World in Las Vegas, promising to perform a special show on his 100th birthday. Executives joked about betting against him living that long, but he performed sold-out shows deep into his nineties. He’d joke that the last time he played Caesars Palace, it was owned by Julius. The line never failed, because the audience wasn’t just laughing at the joke; they were laughing at the fact he was still standing there to tell it.

In 1984, at eighty-eight, he underwent triple bypass surgery. Most people would disappear for a year. He was back filming Oh, God! You Devil within months, sometimes working from a wheelchair and hiding it from the camera. His determination rattled everyone around him, because it was less like ambition and more like refusal.

In 1988, at ninety-two, he received Kennedy Center Honors. He performed a duet with Bette Midler. Later that year, he released Gracie, a Grammy-winning album that blended his voice with archival recordings of hers. Fans cried hearing them together again. It felt like he’d reached through time to take her hand one more time—then time, as always, kept walking.

In July 1994, at ninety-eight, he slipped in his Beverly Hills bathtub, hit a soap dish, and badly gashed his head. At Cedars-Sinai, doctors noticed his speech was slurred. They performed emergency surgery to relieve fluid from his brain. He had to cancel his long-awaited Caesars Palace show that had sold out more than a year before. His health never fully returned. His performing career ended after more than eighty years, but he still tried to make people laugh from a hospital bed. He told stories to friends like Milton Berle and dictated new lines to feel alive.

In December 1995, too weak for the official celebration, he held a small private party at home. He handed out cigars and told guests he’d see them at 101. On January 20, 1996, he turned one hundred. Less than two months later, on March 9, 1996, he died at home from cardiac arrest.

The public heard the news in the familiar, careful language of broadcasters: he died in his bed at his home in Beverly Hills, he’d been sick in recent months but had been feeling better lately. People replayed old clips, laughed softly, felt that strange grief you feel for someone you never met but somehow grew up with anyway. And then the estate details surfaced, and that refrigerator flag magnet didn’t seem so innocent.

His estate, valued at more than $30 million, went to auction at Sotheby’s in Beverly Hills on October 10, 1996. There were 266 lots—scripts, cigars, the artifacts of a life spent turning ordinary things into props. Two hundred sixty-six is a clean number until you realize it’s a life divided into pieces you can bid on.

Where did the money go? Not to the kids. Not to the neat ending everyone expected. He left everything to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, the United Jewish Fund, and the Motion Picture & Television Fund. Sandra and Ronnie received nothing. Some people were shocked, because shock is what we call it when a story refuses to behave. Those who knew him understood charity had become his final way of giving back—back to the hospital that treated him, back to the community that shaped him, back to the industry that fed him and almost devoured him.

Still, the questions didn’t stop. “How do you cut out your own children?” people asked, as if the word “children” automatically solved the math. Friends, trying to explain without betraying anyone, talked about secrets Burns never told, about a betrayal years earlier that left a scar he never displayed in public. Maybe it wasn’t one event. Maybe it was a slow accumulation of disappointment, the kind that doesn’t explode like a prop cake but quietly changes where you sign your name.

A friend remembered George looking at a stack of papers late in life, the cigar holder resting in his fingers like a conductor’s baton. “You sure?” the friend asked.

George didn’t look up. “I’ve been sure for a long time.”

“But they’re your—”

George finally raised his eyes, and the look was older than his body. “They’ll be fine. This is where I’m needed.”

People wanted a villain, a reason they could point to like evidence in a courtroom. They wanted a betrayal clean enough to fit into a headline. But the truth, if it existed in one sentence, stayed locked behind the same door George had always used: humor. He could tell you he didn’t tell jokes, he told anecdotes and lies, and then he’d hand you a true story wrapped in a laugh and you’d thank him for it.

In the years after, his influence didn’t fade. Jerry Seinfeld has said George’s book Living It Up shaped how he writes. George’s precise timing, quiet delivery, and straight-man style became part of the backbone of modern comedy. The cigars and martinis became symbols, but doctors later said it was his sharp mind and wide social circle that kept him alive so long. He’d built a life on connection—audiences, partners, friends, a country that let him step out of a scene and speak directly to them.

And maybe that’s why the ending looked the way it did. Maybe the last act wasn’t about punishing anyone. Maybe it was about choosing the widest audience one more time.

Back in that Beverly Hills kitchen, the flag magnet stayed stuck where it had always been, holding nothing more dramatic than a takeout menu and a note with a phone number. Someone lifted a cigar from a box—one of the lots that hadn’t yet become a number—and turned it in their hand like a relic.

“He really did it,” someone whispered, not angry, just stunned.

Another voice, trying to sound certain, said, “He always said it was a true story.”

And somewhere in the memory of his voice, you could almost hear him answer, dry as ever, as if the whole country had leaned in close enough: “I got nothing much to lose. Never get the blues.” Then, after a pause you could drive a laugh through, the kind of pause he’d perfected since the Lower East Side, you could hear the real line underneath the joke—the promise he’d been paying on his whole life.

He didn’t just leave a fortune to one place. He left the punchline to everyone.

News

He Divorced His Wife and Married His Step-Son. She Brutally Sh0t Him 33 Times | HO!!

He Divorced His Wife and Married His Step-Son. She Brutally Sh0t Him 33 Times | HO!! Her name was Melissa…

58-Year-Old Wife Went On A Cruise With Her 21-Year-Old lover- He Sold Her to 𝐓𝐫𝐚𝐟𝐟𝐢𝐜𝐤𝐞𝐫𝐬, AND… | HO!!

58-Year-Old Wife Went On A Cruise With Her 21-Year-Old lover- He Sold Her to 𝐓𝐫𝐚𝐟𝐟𝐢𝐜𝐤𝐞𝐫𝐬, AND… | HO!! The ocean…

After Decades, Lionel Richie Finally Confesses That She Was The Love Of His Life | HO!!

After Decades, Lionel Richie Finally Confesses That She Was The Love Of His Life | HO!! More than seventy years…

THE TENNESSEE 𝐁𝐋𝐎𝐎𝐃𝐁𝐀𝐓𝐇: The Lawson Family Who Slaughtered 12 Men Over a Stolen Pickup Truck | HO!!

THE TENNESSEE 𝐁𝐋𝐎𝐎𝐃𝐁𝐀𝐓𝐇: The Lawson Family Who Slaughtered 12 Men Over a Stolen Pickup Truck | HO!! A man can…

Family Won $20K But Was Promised $50K — Steve Harvey Paid the Difference From His OWN POCKET | HO!!!!

Family Won $20K But Was Promised $50K — Steve Harvey Paid the Difference From His OWN POCKET | HO!!!! Derek…

At 67, Her 5th Marriage To A 33-year-old Instagram Model Cost Him Her Life | HO!!!!

At 67, Her 5th Marriage To A 33-year-old Instagram Model Cost Him Her Life | HO!!!! The little U.S. flag…

End of content

No more pages to load