Subway Workers Followed Strange Noises Underground — And Found Dozens of Missing Children | HO

New York City — For years, unexplained disappearances of children from the city’s outer boroughs languished as cold cases, often labeled runaways and quietly sidelined. Last week, that narrative shattered.

A federal task force, guided by a veteran Metropolitan Transportation Authority maintenance worker and a grieving mother, executed coordinated raids across a network of hidden tunnels and off-book exits linked to the subway — rescuing dozens of children and exposing what authorities now describe as a highly organized trafficking pipeline operating beneath the city.

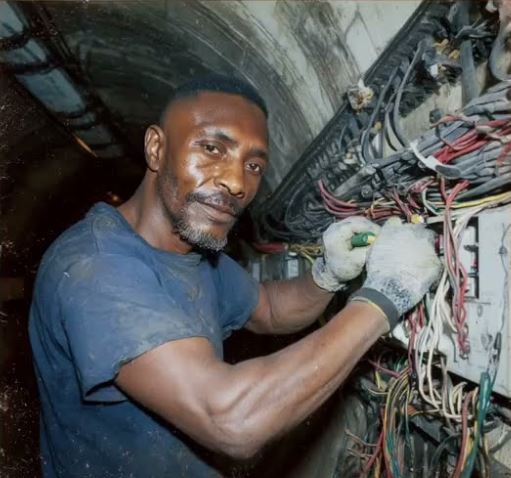

The breakthrough came after months of independent, after-hours legwork by Darnell Jacobs, 44, a two-decade MTA maintenance veteran whose unusually intimate knowledge of the subway’s labyrinth proved pivotal. Jacobs, long dismissed by supervisors for reporting “strange noises” and fresh masonry in sealed areas, teamed up with Maria Torres, a Bronx mother whose 12-year-old son, Leo, vanished two years ago. Together, they assembled a mosaic of evidence the city had failed to recognize — and forced it into the public eye.

What they uncovered, investigators say, was a clandestine transportation network exploiting abandoned stations, forgotten service corridors and unmapped ventilation shafts to move abducted children from point to point with minimal risk of detection.

The operation, described by federal officials as “corporate in structure and logistics,” relied on a chain of low-level abductors and specialized tunnel couriers. The geography was its advantage: a shadow system running parallel to the city’s official circulatory system, largely unmonitored and structurally neglected.

Jacobs’s warnings began as routine incident notes: faint cries in low-traffic tunnels, unexplained drafts, and suspiciously new cinder block walls in supposedly dormant sections. According to internal accounts, his supervisor repeatedly attributed the noises to “acoustic bleed” and high-pressure water mains, and warned Jacobs to “stick to the job.”

Similar complaints, sources say, pinballed for years between the NYPD and MTA, each citing the other’s jurisdiction and resource constraints. The unhoused population and urban legends filled the rest of the official explanation gap.

Two weeks ago, that institutional denial met an undeniable sound. Jacobs and his crew, replacing corroded third rail near a sealed, early-20th-century station, heard what multiple workers describe as a child’s stifled scream coming from behind a closed section. When Jacobs pressed to investigate, management threatened disciplinary action. He went back on his own time.

Using archived prewar blueprints, hand-drawn overlays, and a map of last-known locations of children whose cases had been coded as runaways, Jacobs traced a pattern: surface clusters of disappearances aligning with forgotten infrastructure below. He located a narrow, unmapped shaft half a mile from the sealed station and descended, off the clock, with a flashlight and tools.

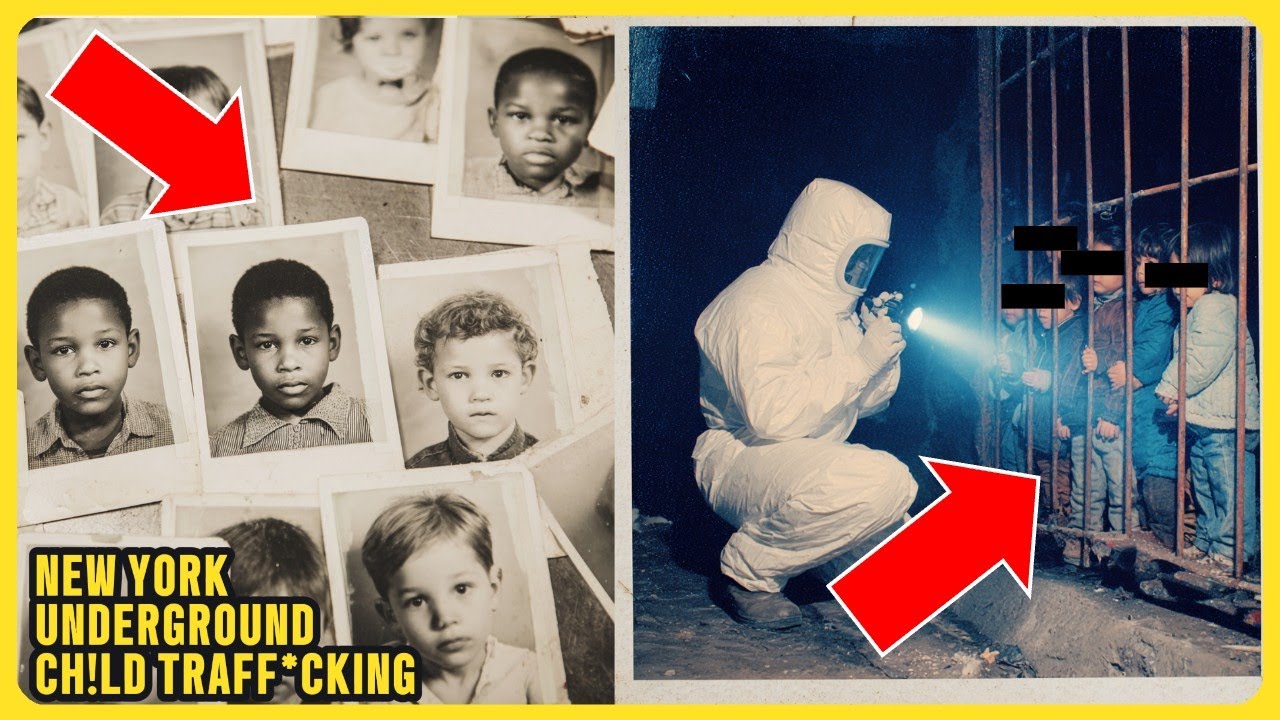

Behind a false plaster wall and a modern steel gate secured with a new chain, he found a rock-cut chamber outfitted as a temporary holding pen: soiled mattresses, empty water bottles, candy wrappers — and a small, worn pink sneaker. A child’s coloring book lay open on the floor. He photographed everything.

Torres took those images not to the precinct but to an investigative reporter at a local digital outlet. Anonymizing Jacobs, the story published under a stark headline and ricocheted across social platforms and national broadcasts within hours.

Protesters gathered outside City Hall; calls flooded the mayor’s office. Amid the uproar, city officials ceded control to a joint federal task force led by the FBI, with Jacobs and Torres brought in as key consultants.

In a windowless conference room at the FBI’s New York field office, the balance of power inverted. NYPD officials, who had long categorized the missing children as runaways, were ordered to turn over files. MTA administrators opened archives and engineering records.

Jacobs unrolled brittle blueprints and traced the tunnel vernacular only he seemed to speak: ghost stations, forgotten valves, bypass galleries, Cold War-era evacuation links. Torres kept the mission’s purpose in focus. “This is not a logistics exercise,” a task force official recalled her saying. “These are rescues.”

What followed, late last week, was a synchronized series of subterranean and surface raids. Guided by Jacobs, federal tactical teams navigated service galleries and concealed doors to breach the sealed chamber he had documented.

It was empty — the mattresses and debris gone. But the chamber, Jacobs insisted, was a waystation, not an endpoint. Behind another disguised seam in the rock, agents forced open a second barrier, revealing a wider conduit leading toward multiple exit points.

Simultaneous teams hit linked surface sites: self-storage units in Queens, an abandoned warehouse in Red Hook, and the shuttered cellar of a former Meatpacking District nightclub.

Behind false walls and staged stacks of boxes, agents found groups of frightened, malnourished children — alive. By dawn, officials confirmed dozens had been recovered across several locations. As of press time, the FBI has not disclosed the total number or released names, citing ongoing identification and reunification efforts.

Federal authorities declined to detail arrests or the hierarchy of the alleged criminal network, describing it as a “compartmentalized logistics enterprise” that outsourced abductions to local actors while centralizing transport and storage in the tunnels. “This was not improvised,” a senior law enforcement official said. “They studied the infrastructure most of us have forgotten and built an invisible highway underneath a city that never stops watching itself.”

The revelations have sparked a reckoning in multiple agencies. City officials face questions about years of missed warning signs and a bureaucratic ping-pong that left families without answers. Budget constraints, jurisdictional ambiguity, and a reliance on folklore — from “mole people” myths to the memory of hoax tunnel screams staged by teenagers years ago — created a potent shield for inaction. “The system was optimized to hear nothing,” one investigator said.

At a secured hospital designated as a reunification center, quiet scenes supplanted the week’s dramatic images. Parents waited, hands clenched, as social workers ushered in children one by one. Maria Torres’s reunion with her son was understated and shattering: no theatrics, just two figures crossing a small room and holding on. Her advocacy — from late-night office cleanings to law library research, vigils outside neighborhood stations, and relentless calls to elected offices — had collided with Jacobs’s solitary mapping of the dark and turned persistence into policy.

Officials have launched multiple internal reviews. The mayor announced an independent audit of neglected infrastructure and ordered a joint MTA–NYPD–FBI assessment of abandoned and sealed corridors, with a mandate to catalog and secure all known offshoots and ventilation shafts. The MTA pledged to modernize subterranean mapping, integrate sensor networks in low-traffic zones, and formalize a channel for front-line worker reports. NYPD leadership signaled changes to how missing child cases are coded and escalated, with a focus on patterns that cross precinct lines and transit infrastructure.

Civil liberties advocates and community groups are pressing for sustained oversight rather than one-time sweeps. “This can’t be a story that spikes and vanishes,” said a Bronx organizer who joined early vigils. “If these tunnels became a blind spot once, they can again.”

For Jacobs, the attention remains unwelcome. He declined interview requests beyond confirming his role as a consultant. Colleagues describe him as “the guy who knows every bolt in the wall” — a quiet presence more at ease pointing to a seam in a blueprint than standing behind a podium. His teenage daughter, according to those close to the family, urged caution as his late-night forays grew riskier. He kept going. “He listens to the city,” one coworker said. “And this time, it screamed back.”

Federal officials caution that the investigation is far from over. The network’s size, financial backers, and out-of-state links are under active review. Forensic teams are still processing the chambers and conduits uncovered underground. The task force has asked the public to report information tied to abandoned properties with unusual ventilation or secure access points, and to revisit cold cases that intersect with former industrial zones connected to transit lines.

Yet amid the unanswered questions, one fact has reshaped the city’s understanding of its own depths: the subway’s forgotten corridors were not just relics — they were weaponized. The same traits that make the system remarkable — redundancy, history, sheer scale — created the conditions for a predatory enterprise to move in silence.

On a bright morning after the raids, Jacobs stood in a hospital corridor with his daughter, watching through a narrow glass pane as Torres and her son held each other. He turned away quietly, colleagues say, to let the door close and the room remain theirs. Outside, cameras clustered on the sidewalk, the city’s noise returning to its usual pitch. Below, crews fanned out with fresh maps and new orders. Above, families waited for names to be read.

The tunnels will be audited and sealed, officials promise. Sensors will go up. Reporting lines will change. But those who lit candles at small vigils in outer-borough station entrances say the lesson is simpler: listen — to the mothers who refuse to stop calling, and to the workers who hear what the rest of the city writes off as pipes.

News

2 HRS After He Traveled To Visit Her, He Found Out She Is 57 YR Old, She Lied – WHY? It Led To…. | HO

2 HRS After He Traveled To Visit Her, He Found Out She Is 57 YR Old, She Lied – WHY?…

Her Baby Daddy Broke Up With Her After 14 Years & Got Married To The New Girl At His Job | HO

Her Baby Daddy Broke Up With Her After 14 Years & Got Married To The New Girl At His Job…

Billionaire Meets a Poor Girl Crying Beside His Son’s Memorial—What She Said Shocked Him | HO

Billionaire Meets a Poor Girl Crying Beside His Son’s Memorial—What She Said Shocked Him | HO The girl lifted her…

He had been expecting the baby for 12 months, but he found his wife had 𝐬𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐞𝐝 him — so 𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐡𝐨𝐭 𝐡𝐞𝐫 | HO

He had been expecting the baby for 12 months, but he found his wife had 𝐬𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐞𝐝 him — so 𝐡𝐞…

𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 charge for groom who 𝐤𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐞𝐝 stepfather at wedding; sheriff says it’s self defense | WSB-TV | HO

𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 charge for groom who 𝐤𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐞𝐝 stepfather at wedding; sheriff says it’s self defense | WSB-TV | HO Another line,…

Wealthy Widow Had A Love Affair With A Prisoner — He Got Out & She Was Found 𝐃𝐞𝐚𝐝 … | HO

Wealthy Widow Had A Love Affair With A Prisoner — He Got Out & She Was Found 𝐃𝐞𝐚𝐝 … |…

End of content

No more pages to load