The Black Chemist Who Invented Plastics — And They Erased Him | HO

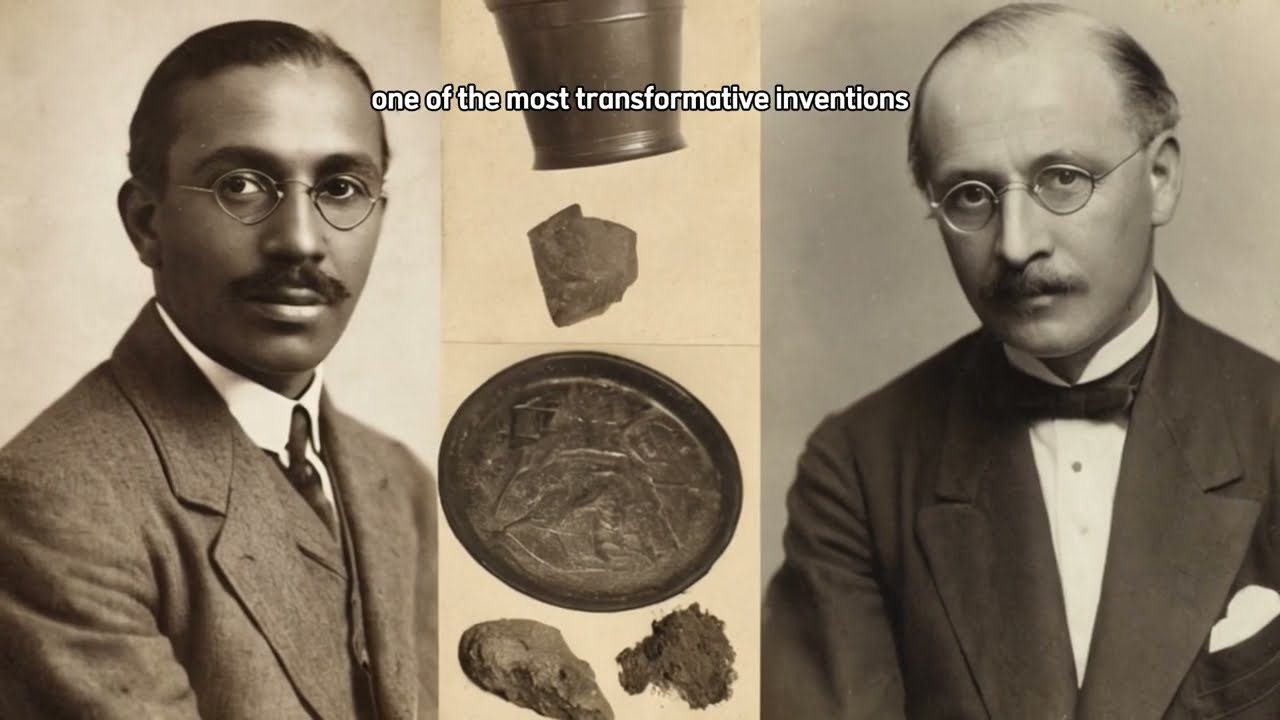

In every classroom, museum, and industry archive, the story of plastics is told as a triumph of European and American ingenuity. Names like Alexander Parkes, John Wesley Hyatt, and Leo Baekeland are enshrined as pioneers whose inventions—Parkesine, celluloid, Bakelite—ushered in the age of synthetic materials and transformed the modern world.

But beneath this polished narrative lies a deliberate erasure, a story suppressed by the politics of race and power: the groundbreaking contributions of Black chemists whose work shaped the very foundation of plastics, only to be buried under layers of silence.

As the world confronts the environmental legacy of plastics, the time has come to reckon with the hidden history of the Black scientific minds who helped create them—and whose legacies were stolen.

A Revolution in Chemistry, Built on Exclusion

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw a seismic shift in industrial chemistry. Factories clamored for new materials as ivory, tortoiseshell, and horn became scarce, expensive, and ethically fraught. Chemistry promised solutions, and the age of plastics dawned.

Yet, as white inventors and industrialists raced to patent the future, Black scientists faced systematic barriers at every turn. Their discoveries were often co-opted, their patents challenged, their achievements buried beneath the weight of racial prejudice.

This was the era when George Washington Carver, a Black agricultural chemist, was conducting experiments that would set the stage for the bioplastics revolution—decades before the petroleum industry monopolized the field. And yet, Carver’s name is rarely mentioned in the standard histories of plastics.

The Forgotten Genius of George Washington Carver

Most Americans know Carver as “the peanut man,” an agricultural innovator who gave Southern farmers new uses for their crops. This folksy caricature, repeated in textbooks and children’s stories, obscures a far more radical truth: Carver was at the cutting edge of polymer chemistry, developing plant-based plastics, adhesives, and synthetic rubbers in his Tuskegee Institute laboratory throughout the 1920s and 1930s.

Carver’s work was not a curiosity—it was a blueprint for the sustainable materials scientists now seek in the 21st century. He collaborated directly with industrial giants. In 1940, Henry Ford unveiled a car with panels made from Carver’s agricultural plastics, publicly crediting Carver’s research and inviting him to demonstrate the material’s strength. Photographs show Carver striking the plastic panels with an axe to prove their durability.

Yet this episode is rarely told as part of the plastics story. Instead, the narrative jumps from Baekeland’s Bakelite to DuPont’s nylon, skipping over Carver’s innovations as if they were mere footnotes. Why?

Race and the Politics of Scientific Memory

The answer lies not in chemistry, but in the politics of race. The early 20th-century scientific establishment was deeply segregated. Black scientists were routinely denied access to journals, conferences, and professional societies.

Carver published little in mainstream venues—not for lack of rigor, but because white chemists and editors refused him a platform. His research, distributed through Tuskegee bulletins and agricultural reports, was dismissed by the gatekeepers of industrial science.

When industrialists like Ford saw the value in Carver’s work, they engaged with him privately, benefiting from his insights while history erased him from the patent record. Carver’s plastics predated the petroleum-based explosion of synthetic polymers, but because they were derived from crops, they were written off as rural curiosities rather than the future of material science.

This was no accident. The mainstream industrial narrative was curated to reinforce white progress and marginalize Black genius. The exclusion of Carver—and other Black chemists—from the story of plastics was a reflection of the broader structure of scientific racism.

Walter Lincoln Hawkins: The Man Who Made Plastics Durable

Carver was not alone. In the mid-20th century, Dr. Walter Lincoln Hawkins, one of the first African-American scientists at Bell Laboratories, revolutionized the practical use of plastics. Hawkins invented a polymer coating that protected telephone cables from environmental damage. Before his innovation, polyethylene-insulated wires cracked under sunlight and weathering, hampering the spread of telecommunications.

Hawkins solved this by adding stabilizers to the polymer, creating a durable plastic that allowed telephone infrastructure to expand globally. His work was essential to the backbone of modern communication—but his name is missing from the grand story of plastics, overshadowed by white contemporaries celebrated in industrial journals and corporate histories.

The erasure of Hawkins and Carver from the plastics narrative is not an isolated case. Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, Black inventors’ patents were stolen, contested, or attributed to employers. Scientific prestige, built on publications and recognition, was systematically denied to Black chemists, whose work was ignored, plagiarized, or reframed through white colleagues.

How Erasure Shapes the Story of Plastics

When plastics became a global industry after World War II, the narrative was streamlined to emphasize wartime necessity and postwar consumer boom. Nylon stockings, Tupperware, and polystyrene were marketed as miracles of modern chemistry. Corporations like DuPont, Dow, and General Electric framed themselves as the sole pioneers of innovation.

Within this industrial mythology, there was no room for Carver’s agricultural plastics or Hawkins’ polymer stabilizers. The story reinforced the narrative of white industrial progress, leaving Black chemists as marginal figures—if they were mentioned at all.

This selective memory not only deprived these scientists of recognition but also distorted the history of chemistry itself, narrowing it into a Euro-American industrial tale rather than a global and inclusive account.

Reclaiming the Lost Legacy

When we re-examine the record, the truth is clear. Plastics were not solely the product of white chemists in corporate labs. They were also the result of Black chemists working in agricultural stations, university laboratories, and industrial research centers—often under hostile conditions.

Carver’s experiments with resins and plastics from peanuts and soybeans provided a renewable vision for material science that was ignored until the 21st century. Hawkins’ innovations made possible the telecommunications network of the modern world. Countless unnamed Black laboratory workers contributed to experiments whose credit went to their white supervisors.

Their fingerprints are all over the birth of modern plastics, even if the official story erased them.

Why This History Matters Now

The urgency of this story is not just about the injustice of the past. By erasing Black chemists from the narrative, history reinforced the false idea that scientific genius is racially exclusive—a distortion that still echoes in the underrepresentation of Black students in STEM fields today.

Recovering the erased legacy of Black chemists is more than an act of historical justice. It expands our understanding of how innovation happens. Science has always been a collaborative, multicultural endeavor, even if history books tried to suggest otherwise.

Ironically, the field that once erased these chemists is now circling back to their vision. As the world confronts a plastics crisis—with petroleum-based polymers choking oceans and overwhelming landfills—scientists are once again turning to plant-based bioplastics as a sustainable solution. Modern researchers working with biodegradable plastics are following the trail blazed by Carver a century ago.

If history had recognized his role, Carver might have been celebrated not only as an agricultural chemist but as the father of sustainable plastics. Instead, that recognition is only now beginning to surface in scholarly re-evaluations long after his lifetime.

The Path Forward: Restoring the True Story

The silence surrounding Black chemists in the history of plastics was not an accident, but a reflection of structural racism that shaped which stories were told and which were buried. To restore this history requires more than just acknowledging names like Carver and Hawkins—it means fundamentally rewriting the way we tell the story of science.

We must look beyond patents and corporate records to see the laboratories of Tuskegee, the research centers that quietly employed Black chemists, and the intellectual contributions dismissed because of skin color. Only then can we tell the true story of how plastics came to define the modern age.

History is not just about who invented what, but about who is remembered and who is forgotten. The Black chemists who helped create modern plastics were not forgotten by accident. They were erased by design. Now, more than ever, it is our responsibility to bring their names back to the surface, honor their genius, and recognize that the modern world is built not only on the discoveries of the few, but on the hidden brilliance of those denied their rightful place in history.

News

Steve Harvey stopped Family Feud and said ”HOLD ON” — nobody expected what happened NEXT | HO!!!!

Steve Harvey stopped Family Feud and said ”HOLD ON” — nobody expected what happened NEXT | HO!!!! It was a…

23 YRS After His Wife Vanished, A Plumber Came to Fix a Blocked Pipe, but Instead Saw Something Else | HO!!!!

23 YRS After His Wife Vanished, A Plumber Came to Fix a Blocked Pipe, but Instead Saw Something Else |…

Black Girl Stops Mom’s Wedding, Reveals Fiancé Evil Plan – 4 Women He Already K!lled – She Calls 911 | HO!!!!

Black Girl Stops Mom’s Wedding, Reveals Fiancé Evil Plan – 4 Women He Already K!lled – She Calls 911 |…

Husband Talks to His Wife Like She’s WORTHLESS on Stage — Steve Harvey’s Reaction Went Viral | HO!!!!

Husband Talks to His Wife Like She’s WORTHLESS on Stage — Steve Harvey’s Reaction Went Viral | HO!!!! The first…

2 HRS After He Traveled To Visit Her, He Found Out She Is 57 YR Old, She Lied – WHY? It Led To…. | HO

2 HRS After He Traveled To Visit Her, He Found Out She Is 57 YR Old, She Lied – WHY?…

Her Baby Daddy Broke Up With Her After 14 Years & Got Married To The New Girl At His Job | HO

Her Baby Daddy Broke Up With Her After 14 Years & Got Married To The New Girl At His Job…

End of content

No more pages to load