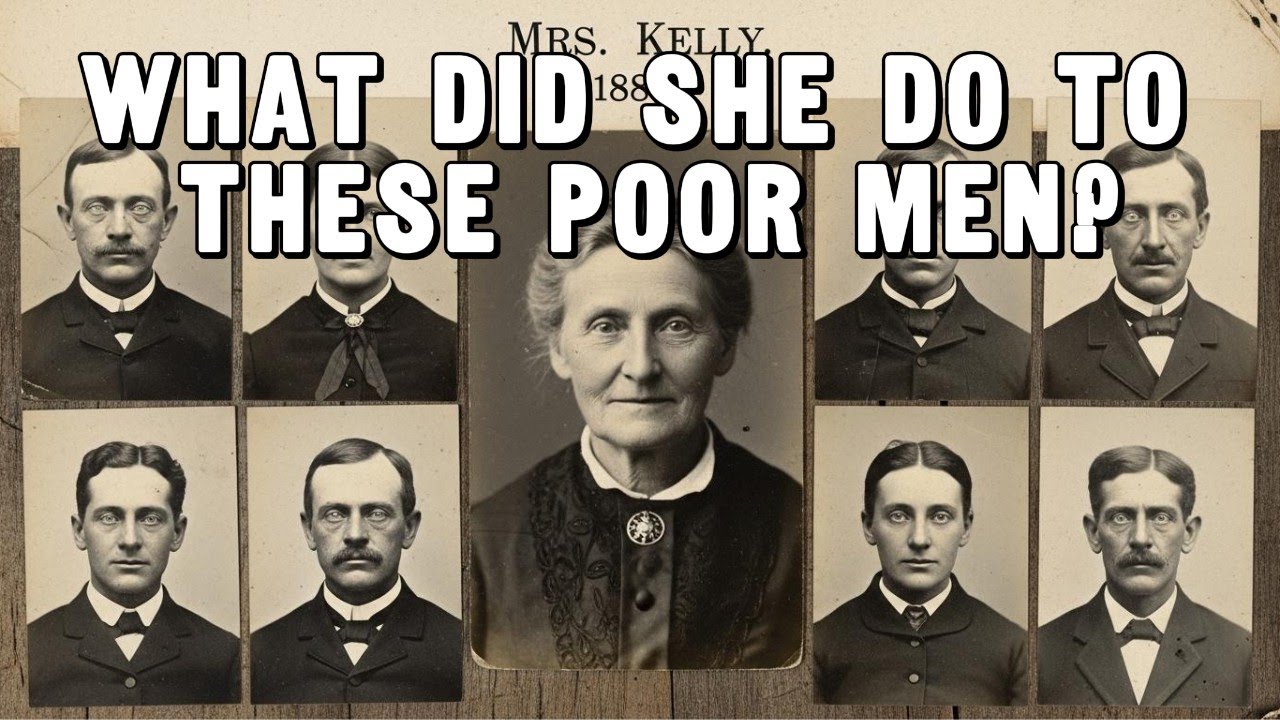

The Boarding House Massacre: Mrs. Kelly’s Method for Disposing of 34 Guests – Virginia 1889 | HO!!

In the annals of American crime, few cases have been as chilling—and as shrouded in secrecy—as the events that unfolded at Mrs. Bridget Kelly’s boarding house in Richmond, Virginia, during the winter of 1889.

For more than a century, the true story of the “Boarding House Massacre” remained buried in sealed city archives, whispered only in hushed tones among local historians and church elders. But now, newly uncovered documents and survivor testimony shed light on a crime so shocking that it shook the foundations of faith and trust in a city still healing from the scars of war.

A Sanctuary Turned Into a Chamber of Death

Richmond in the late 1880s was a city in transition. The wounds of the Civil War were slowly closing, and the Methodist community on Clay Street stood as a beacon of moral authority.

When Mrs. Bridget Kelly—a middle-aged Irish widow with an impeccable reputation—offered to open her late husband’s house as a Christian boarding establishment, her proposal was welcomed with open arms. Church leaders, led by the revered Reverend Thomas Wittmann, saw Kelly’s boarding house as a sanctuary for traveling ministers, missionaries, and church members in need of safe lodging.

The house at 1247 Marshall Street was grand, boasting 12 rooms, ornate woodwork, and a wraparound porch. Mrs. Kelly herself was a familiar figure in Richmond’s religious circles, known for her piety, charitable work, and tragic personal history—her husband lost to consumption, her only son to a railroad accident. She attended services twice weekly, contributed to the poor box, and could recite scripture with the fluency of a seminary graduate.

Within weeks, the boarding house became the preferred destination for visiting clergy and church workers. Guests praised Mrs. Kelly’s hospitality, generous meals, and nightly Bible readings. Many described her as “a mother to us all.” By Christmas of 1888, the house was rarely empty.

The Pattern of Disappearances

But beneath the surface of Christian charity, a disturbing pattern began to emerge. Guests who checked in for a few days stayed for weeks, then months. Letters home dwindled, then stopped altogether. Family members seeking to visit were politely turned away with explanations—illness, prayer, or special projects for the church.

No one questioned these absences; in an era when privacy was sacred and the word of a church member was above reproach, suspicion was slow to take root.

It was not until January 1889 that the first cracks appeared. Emma Ashford, a local schoolteacher, became alarmed when her sister Dorothy, a church organist, had not written or visited in weeks. Repeated attempts to see Dorothy were rebuffed by Mrs. Kelly, whose explanations grew more elaborate with each passing day.

Finally, on January 28th, Emma forced her way into the house, only to find the upper floors eerily silent and the guest rooms locked from the outside. A faint, sweet odor hung in the air. Emma heard what she believed to be her sister’s voice—a moan or whimper—from behind a locked door, but was dragged away by Mrs. Kelly and dismissed by police as a hysterical spinster.

Unraveling the Truth

Emma’s persistence, however, began to stir unease among the Methodist community. Other families reported missing correspondence from loved ones staying at the boarding house.

Reverend Wittmann recalled ministers who had vanished from their circuits, and church members who failed to arrive at their next appointments. Dr. Marcus Webb, a physician who treated several guests, noticed a disturbing trend: fatigue, confusion, and memory problems consistent with chronic poisoning.

Emma’s investigation revealed that Mrs. Kelly was collecting mail for guests no longer present, forging signatures, and withdrawing funds from their accounts. She had been corresponding with churches across the South, identifying vulnerable, isolated individuals—often single, traveling clergy—and inviting them to her “sanctuary.”

The Basement Discovery

The breakthrough came when Mrs. Kelly announced she would be away for a week at a Christian women’s conference. On February 15th, Dr. Webb and Emma Ashford broke into the house, determined to uncover the truth. What they found in the basement was beyond anything they had imagined.

The stone-walled basement was divided into chambers. The first contained household supplies; the second, a makeshift laboratory with bottles of laudanum, morphine, and chloral hydrate—enough opiates to keep dozens of people in a stupefied state for months. A wooden box contained forged letters to families, all in Mrs. Kelly’s handwriting.

But the true horror lay in the fourth chamber: a morgue lined with zinc-lined coffins. Fourteen bodies, meticulously preserved, their faces serene, dressed in their own clothes and arranged with religious care. Each corpse had a placard with the name, date of arrival, and date of death.

Dr. Webb’s examination revealed death by gradual poisoning—small doses over weeks or months, leading to organ failure and death. Mrs. Kelly had played God, deciding who lived and who died, extracting money and possessions before disposing of her victims.

In a fifth room, Emma found her sister Dorothy—alive but heavily drugged, dressed for burial, her hands folded in prayer. A placard on the bedside table indicated Mrs. Kelly had planned Dorothy’s death for March 1st, 1889.

The Confrontation

As they attempted to escape, Mrs. Kelly returned unexpectedly, trapping them in the basement. What followed was a tense confrontation, with Mrs. Kelly calmly explaining her “ministry”—the belief that she was providing eternal peace to suffering souls. She confessed to killing her own husband, Patrick, with an overdose of opiates, and claimed divine inspiration for her subsequent crimes.

Emma and Dr. Webb managed to subdue Mrs. Kelly using a combination of quick thinking and the very poisons she had intended for them. With the help of a confused, drugged accomplice, they escaped and summoned the police.

Aftermath and Legacy

The crime scene at 1247 Marshall Street shocked Richmond and the nation. Thirty-four bodies were recovered, all victims of Mrs. Kelly’s lethal hospitality. The investigation revealed a scheme that targeted the most vulnerable—traveling clergy, missionaries, and church workers—isolated individuals with few family ties. Mrs. Kelly had stolen more than $47,000 (nearly $1 million today) through fraud, forgery, and theft.

The Methodist Church, devastated by its role in recommending the boarding house, instituted new protocols for lodging clergy. Reverend Wittmann resigned, and the city council ordered the house demolished. In 1941, a memorial garden was planted with 34 white roses in honor of the victims.

Mrs. Kelly was tried and convicted on 34 counts of murder, but died by suicide in her cell before her scheduled execution. Her final note read, “I go now to join my children in paradise.”

Lessons Learned

The Boarding House Massacre remains a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked trust and the vulnerability of faith communities to exploitation. Mrs. Kelly’s crimes were made possible by her reputation, her mastery of religious rhetoric, and the isolation of her victims. The case led to stricter regulation of boarding houses and better oversight of church funds.

Emma Ashford, whose persistence saved her sister and exposed the crimes, became a reluctant celebrity, but found little solace in the attention. Dr. Webb advocated for medical oversight of establishments housing vulnerable populations.

More than a century later, the story of Mrs. Kelly’s boarding house reminds us that evil can hide behind the façade of piety—and that sometimes, the greatest monsters are those who convince us they are saving our souls.

News

Steve Harvey stopped Family Feud and said ”HOLD ON” — nobody expected what happened NEXT | HO!!!!

Steve Harvey stopped Family Feud and said ”HOLD ON” — nobody expected what happened NEXT | HO!!!! It was a…

23 YRS After His Wife Vanished, A Plumber Came to Fix a Blocked Pipe, but Instead Saw Something Else | HO!!!!

23 YRS After His Wife Vanished, A Plumber Came to Fix a Blocked Pipe, but Instead Saw Something Else |…

Black Girl Stops Mom’s Wedding, Reveals Fiancé Evil Plan – 4 Women He Already K!lled – She Calls 911 | HO!!!!

Black Girl Stops Mom’s Wedding, Reveals Fiancé Evil Plan – 4 Women He Already K!lled – She Calls 911 |…

Husband Talks to His Wife Like She’s WORTHLESS on Stage — Steve Harvey’s Reaction Went Viral | HO!!!!

Husband Talks to His Wife Like She’s WORTHLESS on Stage — Steve Harvey’s Reaction Went Viral | HO!!!! The first…

2 HRS After He Traveled To Visit Her, He Found Out She Is 57 YR Old, She Lied – WHY? It Led To…. | HO

2 HRS After He Traveled To Visit Her, He Found Out She Is 57 YR Old, She Lied – WHY?…

Her Baby Daddy Broke Up With Her After 14 Years & Got Married To The New Girl At His Job | HO

Her Baby Daddy Broke Up With Her After 14 Years & Got Married To The New Girl At His Job…

End of content

No more pages to load