The Mississippi Blood Oath of 1974: The Carter Brothers Who sʟᴀᴜɢʜᴛᴇʀᴇᴅ 11 Men Over a Gambling Debt | HO

On the night of September 14, 1974, inside a converted tobacco warehouse on County Road 49 in rural Yazoo County, Mississippi, eleven men were shot dead over the span of six unbroken hours. They were farmers, mechanics, a sheriff’s deputy, and drifters drawn to a Saturday night poker game. Most died huddled in a corner, pleading for their lives. Three died outside while trying to run. Every one of them was killed execution-style.

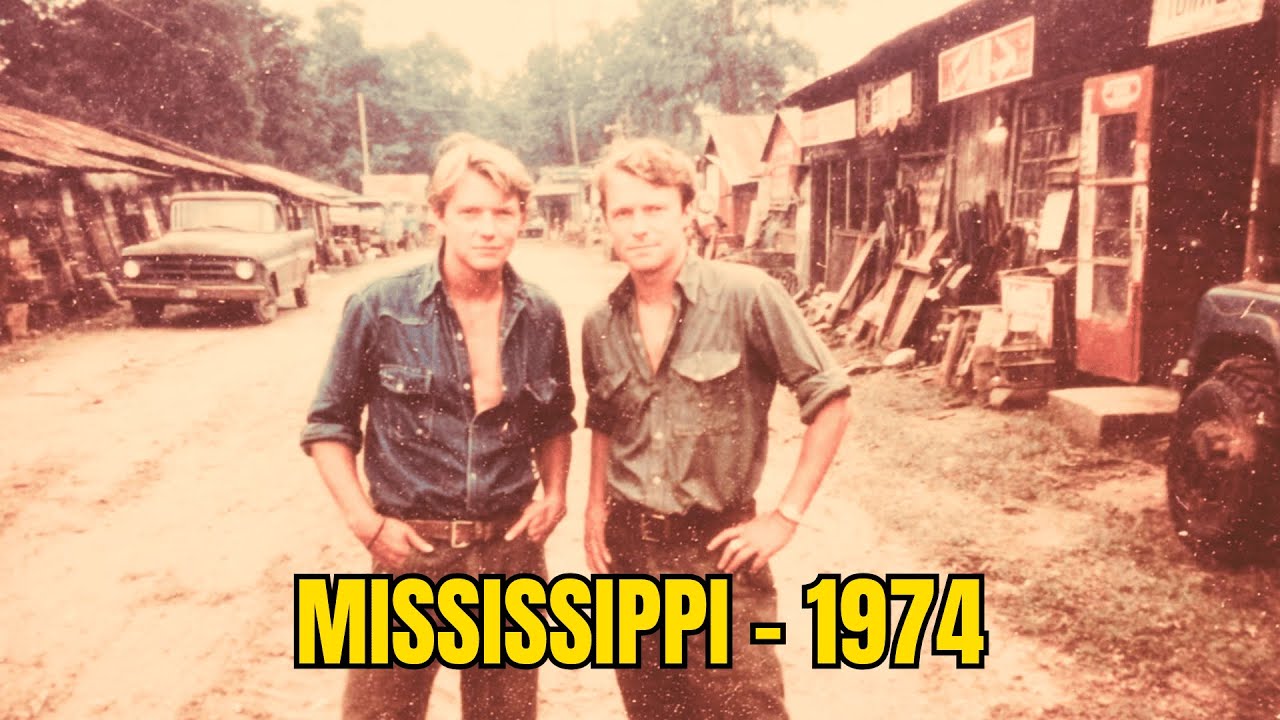

The perpetrators were not gangsters, cartel soldiers, or members of the Dixie Mafia, though all of those groups were active in the area at the time. They were two brothers—James Lee Carter, age 34, a Vietnam veteran and farmer, and his younger brother, 29-year-old mechanic Robert “Bobby” Carter.

Law enforcement officials would later call it “the most calculated rural massacre in Mississippi history.” But long before investigators declared it mass murder, the story began with something deceptively small and painfully ordinary: an $8,500 predatory loan, a fraudulent land deed, and a dying father who believed the system had humiliated him for the last time.

What happened next would fracture Yazoo County for decades, split families, divide churches, and force residents to confront uncomfortable truths about justice, desperation, and what people become when the institutions meant to protect them collapse.

This is the story of the Mississippi Blood Oath of 1974.

A County Suspended in Time

In the 1970s, Yazoo County sprawled across 934 square miles of Delta flatland, a place where the earth seemed to breathe through cotton rows and soybean fields. The September heat that year hung heavy, even after sunset, the air thick with humidity and the smell of turned dirt. By nightfall, darkness swallowed the back roads so completely that even headlights seemed swallowed whole.

Silver City, technically a town but barely more than a cluster of houses and a general store, sat about twelve miles west of Yazoo City. With a population of roughly 400 on a full Sunday after church, it was the sort of place where everyone knew your business—sometimes before you did.

It was also the kind of place where men gathered in barns or backrooms to gamble away the fear of bills they couldn’t pay and land they couldn’t keep. By 1974, cotton prices had fallen. Small farms were collapsing under medical debt, bad harvests, and loans written to be impossible to repay. The Dixie Mafia—less an organized syndicate than a loose alliance of violent opportunists—took advantage, greasing local deputies, controlling protection rackets, and inserting themselves into gambling circles that served as the county’s pressure valve.

The most popular of these games took place every Saturday night in Turner’s Warehouse, a rusted, long-abandoned tobacco barn converted into a dimly lit gambling hall with a single bulb over the door and a plywood table inside. It was illegal, but tolerated. A few dollars in the right pockets ensured that nobody asked questions.

For two years, James and Bobby Carter were regulars at that table.

The Carters and the Land That Defined Them

James Lee Carter stood six feet one, lean from years of physical labor and war. He had fought in Khe Sanh in 1968, earned a Purple Heart, and came home with scars—one on his eyebrow and many more invisible. He lived on the family farm, 180 acres his grandfather had homesteaded in 1919. It was more than land. It was identity.

His father, Samuel, 68, was dying slowly from emphysema after breathing cotton dust for four decades inside the local gin. Samuel’s medical bills mounted until they dwarfed his savings. And that was when he made the worst decision of his life.

He accepted a loan arranged by Lester “Lucky” Haynes.

Lucky—41, slick-haired, gold rings, polyester suits, English Leather cologne applied far too liberally—ran the Saturday poker game. He wasn’t a farmer. He didn’t work. He fed off those who did.

The loan he arranged for Samuel Carter was designed to fail. And when Samuel fell behind on payments, when the interest ballooned into something impossible to repay, the land deed transferred automatically to Haynes. The paperwork was ironclad. Legal. Predatory. Final.

On September 6, 1974, when Samuel received the letter confirming the transfer of his land, something inside him broke. He collapsed in the kitchen, clutching the notice while gasping for air. By the time the ambulance arrived, he’d suffered a heart attack.

In the hospital, through an oxygen mask, Samuel confessed everything—how he’d trusted Lucky because they were “poker men,” because in Yazoo County a man’s word was supposed to mean something. How wrong he had been.

That night, in the hospital parking lot, James and Bobby sat in silence until midnight. When Bobby finally spoke, it was a question, not a plea.

“We have to do something, don’t we?”

James lit a cigarette in the dark. “Yeah,” he said. “We do.”

What neither brother said aloud—but both understood—was the oath that formed in that moment: if the law would not deliver justice, they would.

The Law Turns Its Back

On Monday, James drove to the sheriff’s office in Yazoo City to speak with Sheriff Tom Beckworth, a man who had seen his share of Delta violence. James explained everything—how Lucky had manipulated his father, how the land was stolen through deceit, how the loan was predatory.

Beckworth sympathized. He also shrugged.

“It’s a civil matter,” he said. “You need a lawyer.”

James didn’t have the money for a lawyer. That was why his father borrowed in the first place.

When James walked out of the sheriff’s office into the brutal Mississippi sun, something inside him hardened for good. The system had failed. There was no recourse.

From that moment forward, the brothers planned not justice, but reckoning.

Preparing for the Blood Oath

On Tuesday, James drove fifty miles south to Vicksburg, where no one knew him, and bought a .45 pistol at a pawn shop. On Wednesday, he sat with maps of Yazoo County spread across his kitchen table, marking routes, calculating law-enforcement response times, charting points of entry and escape.

On Friday, the brothers sat on the back porch drinking beer in silence, remembering childhood summers before Vietnam, before debt, before medical bills, before betrayal.

Neither mentioned what would happen the next night. They didn’t need to.

The Night of September 14, 1974

The massacre began at 9:47 p.m. The air outside the warehouse was humid, thick, buzzing with crickets so loud they seemed to vibrate the earth. Inside, Lucky Haynes and eight regulars played cards under a bare bulb, Sheriff’s Deputy Marcus Webb among them.

When James opened the door, laughter stopped. When Bobby locked the back entrance, fear started.

At 9:51 p.m., when Deputy Webb went for his revolver, James fired the first shot.

What followed was not chaos. It was systematic.

Vernon Tucker ran for the door. Bobby shot him.

Dale Morrison tried to flee toward the back. Bobby shot him too.

Four more were forced into a corner—Tommy Briggs, Ray Sutton, Carl Hendris, and Lucky himself. James spoke to each of them, recounting their roles—some direct, some complicit, some merely silent.

Then he executed them.

By 10:44 p.m., eight men inside the warehouse were dead.

But the night was not over.

Three late arrivals—Jerry Coleman, Patrick Walsh, and Jerry’s 18-year-old nephew, Michael Dunn—had been waiting in a car outside, unaware of the carnage. When they stepped into the parking lot at 10:47 p.m., James and Bobby emerged from the warehouse, guns still warm.

Patrick Walsh ran toward the fields. Bobby shot him.

Michael Dunn ran for the treeline. James caught him.

“I’m just a kid,” the boy whispered. “I don’t know what’s going on.”

“You were just in the wrong place,” James said quietly, before pulling the trigger.

At 10:52 p.m., Jerry Coleman was the final victim.

Eleven men lay dead.

The warehouse’s single bulb still burned.

The Carters drove home in silence.

The Discovery

At 6:47 a.m. the next morning, truck driver Willie Jameson spotted bodies in the gravel outside Turner’s Warehouse. The smell hit him before he reached the door.

“I ain’t never seen nothing like that,” he told investigators later.

By 7:15 a.m., Sheriff Beckworth stood inside the warehouse, staring at carnage he had unknowingly helped create. By 9:15 a.m., the FBI had sealed the scene.

By Sunday night, all of Yazoo County knew what had happened.

But no one agreed on why.

Confessions Without Resistance

Four days later, on September 19, law enforcement surrounded the Carter farmhouse. There was no standoff. No gunfire. No last stand.

James Carter had been sitting on the back porch, drinking coffee, waiting.

He stood when Sheriff Beckworth approached.

“We did what we had to do,” James said. “Now we face what comes.”

Bobby asked only for a final phone call to his wife and son.

Both brothers confessed in full. They offered no excuses. No apologies.

Just the truth.

The Trial That Tore a County Apart

The trial began March 18, 1975. It was moved to Jackson because finding an impartial jury in Yazoo County was impossible. Everyone had known someone—one of the dead, or one of the Carters.

Prosecutors presented overwhelming evidence: ballistics, confessions, timelines, maps. The defense argued temporary insanity caused by extreme emotional distress. They pointed to Samuel Carter’s predatory loan, the land theft, the sheriff’s refusal to intervene.

Prosecutors dismissed it.

“This was not insanity,” they said. “This was premeditated annihilation.”

On March 27, 1975, after nine hours of deliberation, the jury found both brothers guilty on all eleven counts of first-degree murder.

They were sentenced to death. Their sentences were later commuted to life without parole.

James Carter died in prison in 2003.

Bobby lives there still.

The Shattered Families

The massacre ripped through Yazoo County like a storm.

Some families mourned murdered loved ones.

Others mourned the Carters, men they insisted were “good boys pushed too far.”

Deputy Webb’s widow cried in a corner booth of the Silver City Café for weeks.

Lucky Haynes’s daughters changed their last names and moved out of state.

Some residents argued the Carters were demons.

Others argued they were creations of a broken system.

But no one argued they were free of guilt.

A Legacy with No Heroes

The 180 acres of Carter family land—land that sparked the bloodshed—was sold to an agricultural corporation in 1982. Today it is part of a 2,400-acre industrial soybean operation owned by people unaware of the soil’s bloody history.

Turner’s Warehouse burned down in 1998. Teens park beer-drinking trucks there now, unaware that the ground beneath them once ran red.

Sheriff Beckworth never ran for reelection. He died haunted by what he saw.

FBI Agent Harold Briggs retired without ever deciding whether justice had been served.

Pastor Eddie Hinton once said, “This story has no heroes—only consequences.”

He was right.

Fifty Years Later: The Questions Mississippi Still Faces

Fifty years have passed since the massacre. The Delta has changed—but not enough. Predatory loans still trap families. Farms still collapse under debt. People still feel cornered by systems larger than themselves.

The Carters were guilty—undeniably. But they were also victims of a system that failed them, a legal structure that protected predators, and a culture that taught men that honor was worth dying—and killing—for.

Their story forces a brutal question:

What happens when the law no longer protects the people who need it most?

Some say the Carter brothers became monsters.

Others say the system made them that way.

Both may be true.

Justice or Revenge? The Line That Disappears

On the night of September 14, 1974, James and Bobby Carter crossed a line no person should ever cross.

But they crossed it in a world where every institution—law enforcement, lenders, neighbors, the courts—had already crossed theirs.

Eleven men died.

Two brothers lost their freedom.

One family lost everything.

And Yazoo County lost whatever innocence it had left.

James Carter died wondering whether it had been worth it.

Bobby Carter, now 79, still doesn’t have an answer.

And maybe Mississippi never will.

News

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon – Found Hiding 4 Months Later Found Inside TREE’S Hollow, Whispering | HO!!

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon – Found Hiding 4 Months Later Found Inside TREE’S Hollow, Whispering | HO!! Here was…

Nat Turner The Most Feared Slave in Virginia Who 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 55 in 48 Hours and Terrified the South | HO!!

Nat Turner The Most Feared Slave in Virginia Who 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 55 in 48 Hours and Terrified the South | HO!!…

He Told Ozzy Osbourne ‘You Can’t Afford This Vintage Guitar’—Then Ozzy Flipped It Over and Froze Him | HO!!

He Told Ozzy Osbourne ‘You Can’t Afford This Vintage Guitar’—Then Ozzy Flipped It Over and Froze Him | HO!! Ozzy…

He 𝐒𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐞𝐝 Her $25,000 To Use to Marry a Younger Woman – But She Paid Him Back on His Wedding Day| HO

He 𝐒𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐞𝐝 Her $25,000 To Use to Marry a Younger Woman – But She Paid Him Back on His Wedding…

He Invited Her on Her First Yacht Trip — 2 Hours Later, She Was Found With a 𝐓𝟎𝐫𝐧 𝐀𝐧*𝐬 | HO

He Invited Her on Her First Yacht Trip — 2 Hours Later, She Was Found With a 𝐓𝟎𝐫𝐧 𝐀𝐧*𝐬 |…

She Noticed a Foul Smell at His House — When She Found Out Why, She Left Him. Hours Later, He… | HO

She Noticed a Foul Smell at His House — When She Found Out Why, She Left Him. Hours Later, He……

End of content

No more pages to load