The Plantation Master Who Willed Everything to a Slave… and Nothing to His Widow | HO

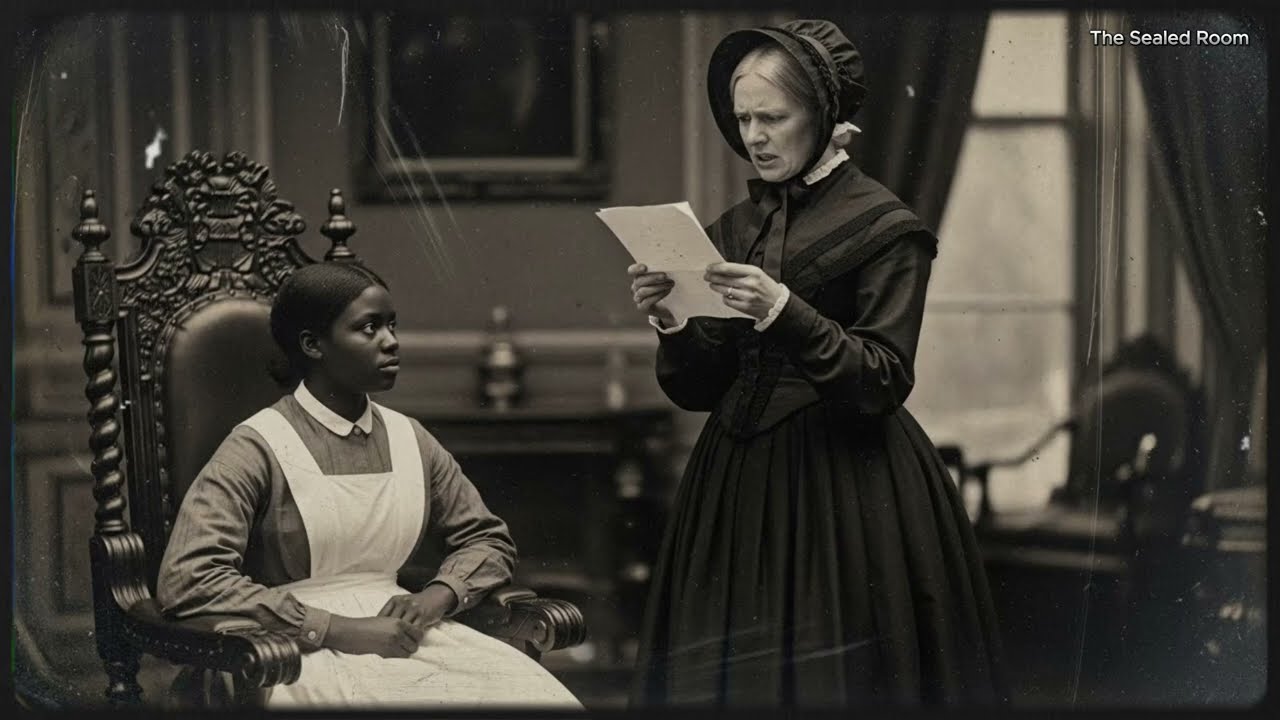

There are moments in history when the façade of an entire society cracks open, when a single document, a single confession, or a single act exposes everything that world has tried to hide. It happened in Natchez, Mississippi, on a hot September morning in 1859, inside a small, wood-paneled law office on Commerce Street. The men there believed they were gathering for an ordinary legal formality—the reading of a wealthy planter’s will. But what they witnessed instead was the collapse of a family, the destruction of a legacy, and the unmasking of a lie upon which the Southern slave system rested like a trembling cathedral.

For forty-seven years, the law firm of Bulmont & Shaw had handled every kind of plantation dispute the Mississippi elite could produce: contested wills, boundary disagreements, the quiet “reassignment” of enslaved children to hide the shame of white men, and the legal gymnastics required to maintain an economy built on human bondage. But nothing in their decades of navigating these unspoken arrangements prepared them for the last will and testament of Colonel Nathaniel James Ashwood.

Because the dying colonel had not left his 2,800-acre estate to his wife.

Nor to his son.

Nor to his daughter.

He left it all—to a woman he had illegally enslaved for seventeen years.

A woman who had stood quietly at the edge of the room while everyone else assumed she was furniture.

And the moment her name was spoken, everything the plantation aristocracy believed about blood, legitimacy, inheritance, and power began to unravel.

The reading room was stifling with September heat. Heavy velvet curtains trapped the air, and the faint scent of law books and old ink seemed to cling to every surface. Victoria Catherine Ashwood, the colonel’s widow, sat in a high-backed leather chair nearest the attorney’s desk. She wore an immaculate black silk mourning dress despite the weather, its stiff bodice a kind of armor. Fifty-one years old, the daughter of Louisiana aristocracy, she had spent thirty-three years married to a man who, she believed, had played his role in their world with perfect precision.

She was about to learn how wrong she was.

Behind her stood her son, Nathaniel Jr., twenty-eight, tall, confident, and already accustomed to running the plantation’s cotton operations as though he were master. At her left sat twenty-five-year-old Caroline, pregnant with her second child, pale from the journey from Memphis but unwilling to miss what she believed was the confirmation of her rightful inheritance.

And standing near the door was the figure whose presence had already scandalized the group: a woman in a plain gray dress, her hands folded, her posture calm and unreadable.

Her name was Esther.

She had no surname. No legal identity except what papers her owner had given her. Purchased in New Orleans seventeen years earlier, she had run the Rosewood Plantation household for nearly two decades with a competence that made visitors uneasy. She was literate. Poised. Trusted by the colonel in ways that were difficult to explain without inviting accusations no Southern household wanted spoken aloud.

Her presence in the room was a violation of every unspoken rule of Southern social order.

But she was there because the colonel demanded it in writing.

And that letter lay sealed on the desk in front of attorney Marcus Bulmont, its wax dark red, almost the color of dried blood.

Bulmont broke the seal with a hesitation that betrayed more unease than he wished the family to see. He had seen the colonel three months earlier, in the final stages of consumption, physically deteriorating and spiritually heavy. It was not unusual for dying planters to seclude their wills, fearing their wives or sons might manipulate them. But there had been something different about Ashwood—something resolute, almost tormented.

Something that suggested he was not merely distributing wealth.

He was detonating a truth.

“I, Nathaniel James Ashwood,” Bulmont began, “being of sound mind though failing body, do hereby declare this my last will and testament. I revoke all previous wills and codicils. What I am about to do will appear to many as madness, to others as betrayal. I can only say that I have spent thirty-three years building a life on foundations I knew were evil, and I will not leave this earth without attempting to destroy what I built and save what I can from the rubble.”

The widow stiffened. Her son stopped gripping the back of her chair and let his hand drop, confusion flickering across his face. Caroline’s breath caught audibly.

Bulmont continued reading, though his voice now trembled.

“To my wife, Victoria Catherine Ashwood, I leave nothing beyond what the law requires. The law grants you your dower rights—one-third of real property for the duration of your natural life. You will have shelter and income, but no authority, no control, no say in how my estate is managed. Your comfort has been purchased by brutality. That comfort ends with my death.”

A strangled sound escaped Victoria’s lips.

“To my son, Nathaniel Jr., I leave my pocket watch and my contempt.”

The young man jolted as if struck, and color flooded his face with outrage.

“To my daughter, Caroline, I leave my mother’s silver service and my regret.”

Caroline’s tears began before she could stop them.

And then the hammer dropped.

“The entirety of my estate, including Rosewood Plantation, the townhouse on Canal Street, all assets, livestock, equipment, and financial holdings totaling approximately three hundred and twenty thousand dollars, I leave to Esther.”

Silence fell so violently that one could almost hear the shift of dust motes in the air. Then the shouting erupted—Victoria screaming, her son pacing like a trapped animal, her brother James Wickham threatening legal action. Caroline sobbed uncontrollably.

Esther did not move.

She stood as she had since entering the room, poised, composed, unreadable.

Bulmont raised a shaking hand. “There is more. Please—there is more.”

When he continued reading, the true horror—and truth—came out.

“I leave everything to Esther not as manumission and bequest, but as return of property illegally held. Seventeen years ago, I purchased a woman who had been unlawfully enslaved. Her mother was free. Legally free. Documented free. Yet the midwife who delivered Esther claimed her as property and sold her. I knew this when I bought her. I saw the documentation. I bought her anyway because she was beautiful and educated, and I wanted to own her.”

Victoria gasped as if struck across the face.

Esther’s hands tightened—but only slightly.

“For seventeen years I have held Esther in bondage knowing she was born free. For seventeen years I used her, relied on her, took from her, knowing every moment was a crime.”

Victoria rose suddenly, her face white.

“This is a lie,” she hissed. “This is—”

“There is more,” Bulmont said gently.

And then came the section that destroyed the plantation hierarchy more completely than any Northern pamphlet or abolitionist sermon ever had.

“During these seventeen years, Esther bore three children: Thomas, born April 1847; Mary, born September 1849; and James, born January 1854. Under the law, children of a free woman are born free regardless of the father. My children with Esther have been free since birth. I forced them, knowingly, to live as slaves.”

Caroline cried out.

Victoria swayed in her chair, gripping the armrests.

The son, enraged, began cursing.

Esther closed her eyes.

The truth was loose now—irrevocable, unstoppable.

The colonel had enslaved a free woman and their free children for nearly two decades.

And the entire world he lived in had allowed him to do it.

Victoria stood. Her voice was low, controlled, terrifying.

“They are not free. My husband’s delusions do not make them free.”

“Mrs. Ashwood,” Bulmont said carefully, “if these documents are authentic—and they appear to be—then your husband is correct. Under Louisiana and Mississippi law, if Esther was born free, her children were born free.”

“Then he—but—” She choked on her words. “Then he imprisoned free children. He—he committed crimes that would destroy—”

She cut herself off.

Everyone knew the end of that sentence.

It would destroy the entire family.

But if she challenged the will, she would have to prove Esther had not been free.

To do that, she would have to expose the very scandal she sought to avoid.

Her dead husband had built a perfect legal trap.

And she was caught.

Bulmont finished reading. Victoria stormed out. Her son followed, livid. Caroline, sobbing, allowed her uncle to escort her out. None of them looked at Esther.

Had they looked back, they would have seen tears sliding silently down her face.

Not of triumph.

But of grief so layered and complicated that no outsider could ever parse it.

Because she had just learned that the man who owned her had also known, from the beginning, that he had no legal right to do so.

What followed over the next two months became one of Mississippi’s most scandalous legal battles—one the newspapers reported cautiously, one that society whispered about, one that the archives later quietly buried.

Victoria, refusing humiliation, hired the most powerful attorneys in the state. They challenged the will on every possible ground: undue influence, mental incompetence, public policy violations, the technical “establishment” of enslaved status over time.

The case landed before Judge William Morrison, a man steeped in planter ideology, a man whose own wealth was built on cotton and slaves. But even he could not ignore the mountain of documentation the colonel had gathered.

Birth records from Haiti. Immigration papers. Legal declarations of free status. Letters. Affidavits. Purchases. Witness statements. A lifetime of evidence compiled in the colonel’s final year, as if he were racing time to confess before hell claimed him.

But the most devastating evidence of all arrived weeks later, in the form of a letter.

A letter addressed to Victoria.

A letter the colonel had written three months before his death.

A letter he intended to be read only if she contested the will.

A letter that would destroy her challenge and her marriage in a single stroke.

Judge Morrison read the letter in chambers. When he returned to the bench, his face had changed. Something in him had aged.

He read parts of it aloud, as the law required.

It began gently. Then sharpened into a blade.

“Victoria, if this letter is being read in court, it means you have chosen to fight my will. Before you destroy Esther to punish me, you must know the truth we never spoke of: I never desired you. I tried. I failed. You felt the distance.”

Gasps rippled through the courtroom.

Victoria sat rigid, the color drained from her face.

“When I purchased Esther, it was not for her literacy. It was because I felt something with her I had never felt with you. I loved you in the way society expected. I loved her in the way a man loves a woman by nature.”

Victoria made a sound that seemed torn from the deepest part of her.

The colonel had confessed everything.

Not just the crimes.

The emotions.

“I enslaved my own children. And that, not adultery, is the sin that haunts me.”

There were tears in the courtroom—some from shame, some from fury, some from the unbearable truth that love and cruelty had been intertwined for seventeen years under one roof.

And then came the most devastating admission:

“Esther did not seduce me. She was fourteen. She could not refuse me. She was never anything but a child forced into the role of wife.”

Victoria’s composure shattered.

And for the first time, the courtroom understood: the colonel’s will was not a gift.

It was a confession.

A confession to crimes that could never be undone.

When asked if she wished to continue the case, Victoria stood.

Everyone braced for another explosion.

Instead, she spoke with a hollow calm.

“No. I withdraw my challenge.”

The courtroom erupted. Her attorneys protested. Judge Morrison pounded his gavel.

But Victoria was unmoved.

“My husband wrote the truth in this letter. I may despise it, but it is truth. And I will not stand in court and deny what we both knew for years. Esther—take what he left you. But understand: it fixes nothing.”

She turned to Esther.

“You will spend the rest of your life explaining to your children why the father who loved them kept them in chains. That burden is yours now. I do not envy it.”

And she walked out of the courtroom.

Three days later, she left Natchez forever.

On November 27, 1859, the court validated the will.

Esther became the legal owner of Rosewood Plantation.

It was unprecedented.

Unthinkable.

A Black woman—born free, enslaved illegally, mother of the colonel’s children—now owned one of Mississippi’s most profitable plantations.

But victory tasted like ash.

Planter society retaliated swiftly. Merchants refused to trade with her. Banks refused her credit. Neighbors refused to acknowledge her existence unless in contempt.

The South could tolerate many sins.

But not this.

Not truth that threatened the bloodlines and property structures upon which the entire system rested.

Within two years, as secession loomed and war approached, Esther sold the plantation for half its value and fled north with her children. She used the colonel’s wealth to buy something far more important than land.

Safety.

Freedom.

A future.

The Civil War destroyed the remaining Ashwood holdings. Cotton collapsed. Confederate investments evaporated. The townhouse was damaged during the siege of Vicksburg. Everything that had built the Ashwood empire—the plantation machinery, the human labor, the inherited wealth—was swept away.

But Esther’s children survived.

Thomas became a teacher.

Mary a seamstress and community organizer.

James a minister.

Each carried the complicated truth of their parentage like a wound and a warning.

Each lived with the knowledge that their father had both loved them—and enslaved them.

Each lived with the documents Esther kept locked in an iron box, proof of their freedom in a world desperate to deny it.

Esther lived until 1894. She never remarried. She wrote a memoir that no publisher dared print at the time—a manuscript that eventually found its way into university archives.

In it, she wrote:

“He built me a cage and called it affection. He kept me as property and called it love. His will did not free me. It only gave me the tools to free myself.”

As for Victoria’s children:

Nathaniel Jr. died fighting for the Confederacy at Shiloh.

Caroline lived out her years as a governess, her fortune gone.

The plantation house still stands, collapsing slowly into the soil. No plaque explains its history. No tours mention the will that nearly collapsed Southern inheritance law. Yet in the Adams County archives, the case remains.

Hundreds of pages.

Testimony.

Confession.

Contradiction.

A society’s hypocrisy laid bare.

Not a story of heroes.

Not a story of villains.

A story of people trapped inside a system too cruel to allow innocence and too powerful to allow truth.

A story of a man who tried too late to correct an unforgivable crime.

A story of a woman whose freedom was stolen, returned, and then weaponized against her.

A story of a widow who discovered the man she married had never existed—not truly.

And a story that poses a question the South never dared answer:

What happens when a man who owns human beings decides, at the end of his life, to tell the truth?

News

He Divorced His Wife and Married His Step-Son. She Brutally Sh0t Him 33 Times | HO!!

He Divorced His Wife and Married His Step-Son. She Brutally Sh0t Him 33 Times | HO!! Her name was Melissa…

George Burns Left His Fortune To ONE Person, You Will Never Guess Who | HO!!

George Burns Left His Fortune To ONE Person, You Will Never Guess Who | HO!! In March of 1996, George…

58-Year-Old Wife Went On A Cruise With Her 21-Year-Old lover- He Sold Her to 𝐓𝐫𝐚𝐟𝐟𝐢𝐜𝐤𝐞𝐫𝐬, AND… | HO!!

58-Year-Old Wife Went On A Cruise With Her 21-Year-Old lover- He Sold Her to 𝐓𝐫𝐚𝐟𝐟𝐢𝐜𝐤𝐞𝐫𝐬, AND… | HO!! The ocean…

After Decades, Lionel Richie Finally Confesses That She Was The Love Of His Life | HO!!

After Decades, Lionel Richie Finally Confesses That She Was The Love Of His Life | HO!! More than seventy years…

THE TENNESSEE 𝐁𝐋𝐎𝐎𝐃𝐁𝐀𝐓𝐇: The Lawson Family Who Slaughtered 12 Men Over a Stolen Pickup Truck | HO!!

THE TENNESSEE 𝐁𝐋𝐎𝐎𝐃𝐁𝐀𝐓𝐇: The Lawson Family Who Slaughtered 12 Men Over a Stolen Pickup Truck | HO!! A man can…

Family Won $20K But Was Promised $50K — Steve Harvey Paid the Difference From His OWN POCKET | HO!!!!

Family Won $20K But Was Promised $50K — Steve Harvey Paid the Difference From His OWN POCKET | HO!!!! Derek…

End of content

No more pages to load